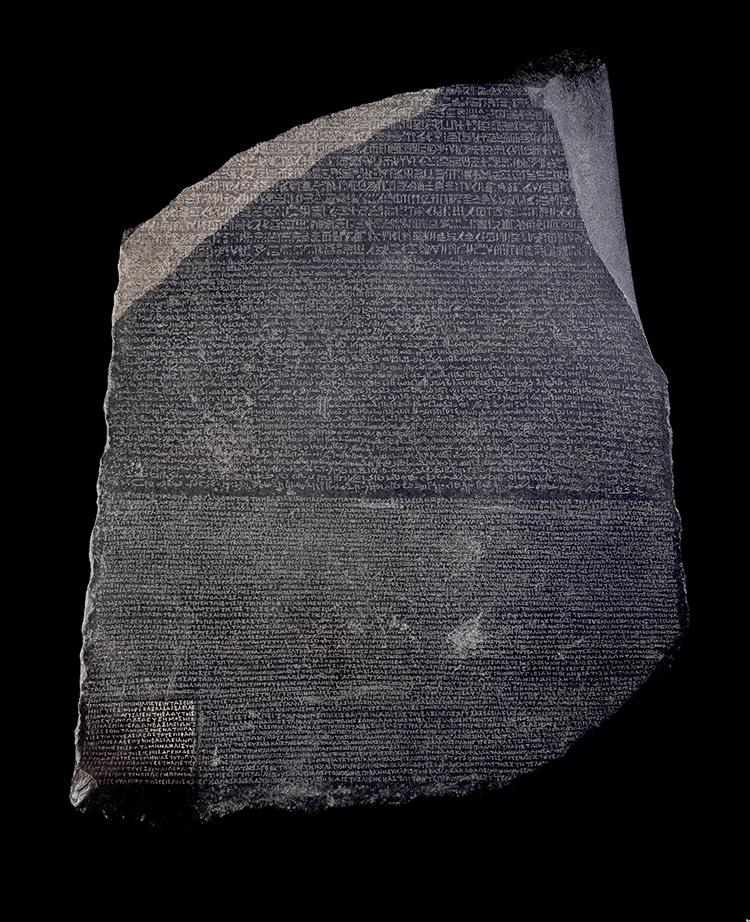

The Rosetta Stone in the collections of The British Museum, London, UK. (Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0])

What is the Rosetta Stone?

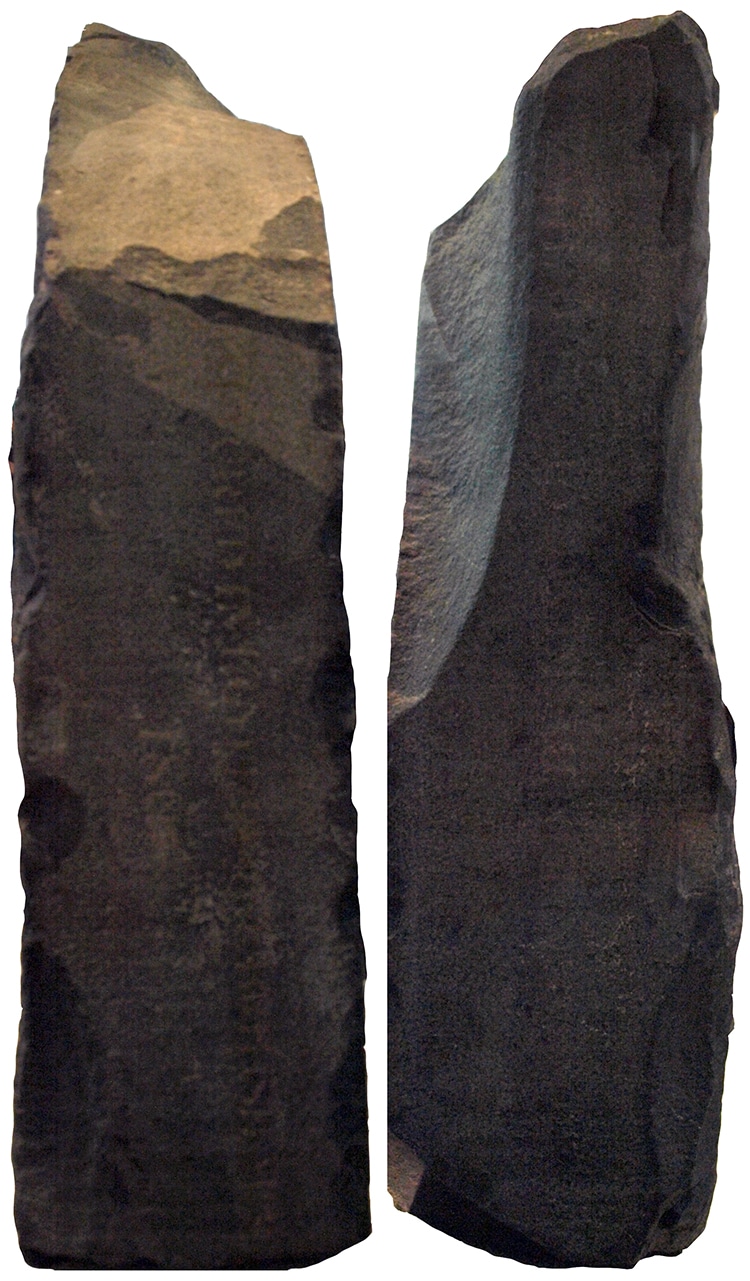

A side view of the Rosetta Stone. (Photo: Cptmondo via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

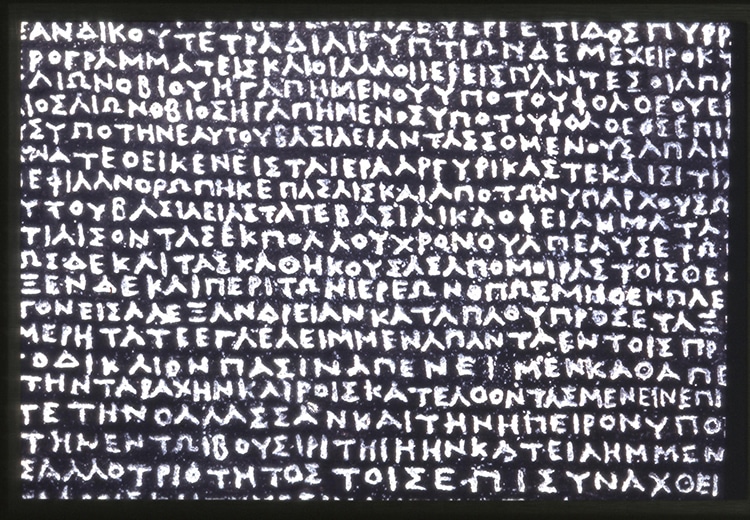

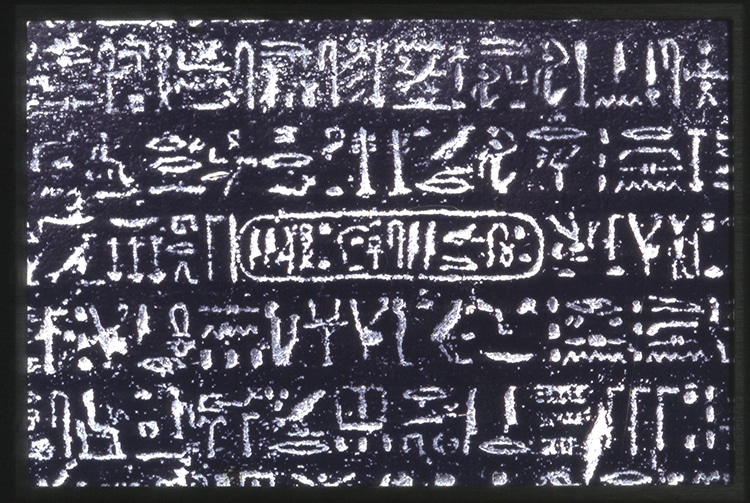

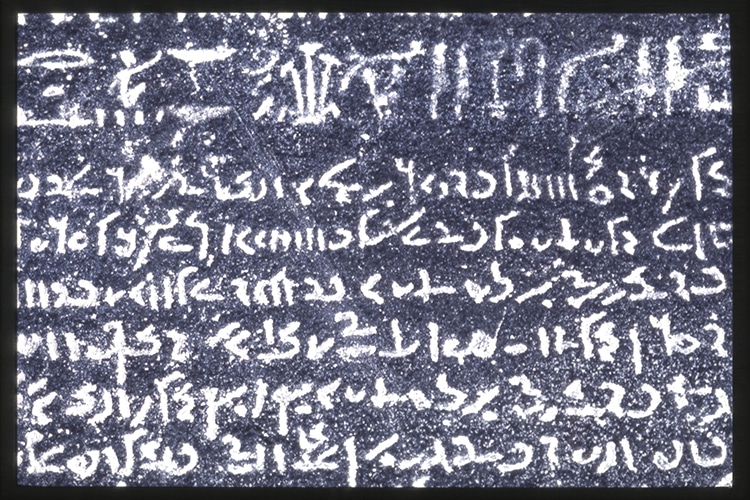

Using the diverse written languages of the Egyptian populace, three languages were included on the stone: Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, Egyptian demotic script, and Ancient Greek. Only the priests regularly used hieroglyphics, whereas demotic script was common in everyday life and civil administration. The inclusion of Ancient Greek reflects the lineage of Hellenistic pharaohs (including Ptolemy V) who ruled Egypt but were originally of Macedonian descent. Ancient Greek was the language of the royal court and therefore fit for a royal decree.

Origin of the Rosetta Stone

An ancient coin depicting Ptolemy V. (Photo: cgb.fr via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

The Rosetta Stone was carved to commemorate the coronation of Ptolemy V in the second century BCE. Egyptian pharaohs were considered gods and commanded a cult of devotion much like other deities. According to the written decree, the monument honored the young king by associating his new cult with those of his Ptolemaic ancestors (the dynasty of successive king Ptolemy's). The stone was likely displayed or inset inside a temple where priests and wealthy worshippers could appreciate their new king's divinity.

The monument likely remained on display for many years. Egypt eventually came under Roman power in the year 30 BCE with the defeat of Cleopatra and Mark Antony. As part of the empire, Egypt was subject to the 4th century Christianization of Rome. In 392 CE the emperor Theodosius I decreed the closure of all non-Christian spaces of worship. Temples were destroyed and the stone reused in other buildings. The Rosetta Stone—not an exceptional object at the time—met the same fate.

A Mamluk fort in Alexandria, built in the same period as the fort containing the Rosetta Stone. (Photo: Delengar via Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0])

Who rediscovered the Rosetta Stone?

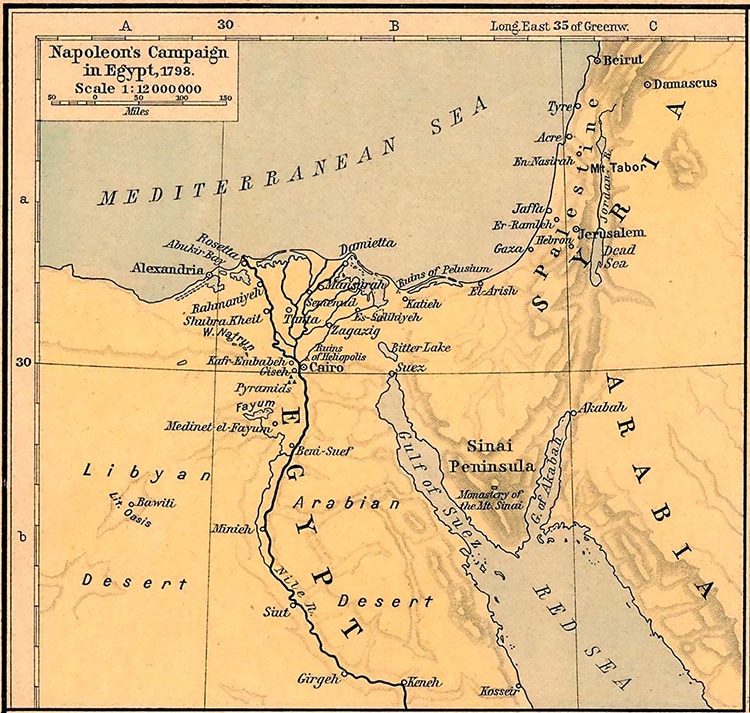

Map of Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

French troops were occupying Rosetta in July of 1799 when a corps of engineers working on the old Mamluk fort discovered a large slab of rock within an earthen wall. The troops knew that this particular find was special, and upon expert examination, the three inscribed languages were identified. Casts of the stone were taken and sent to scholars to examine. The knowledge of hieroglyphics had been lost with the fall of Rome, so the text presented a challenging puzzle to European scholars.

Upon the British defeat of Napoleon, the British acquired the collected antiquities of Napoleon's expeditions—including the Rosetta Stone. In 1802 the stele was installed in the British Museum, where it remains on view to this day. However, the stone's mysterious text had already spread across Europe, and the new field of Egyptology began to develop around the cryptic engraved messages.

How did scholars decipher the stone?

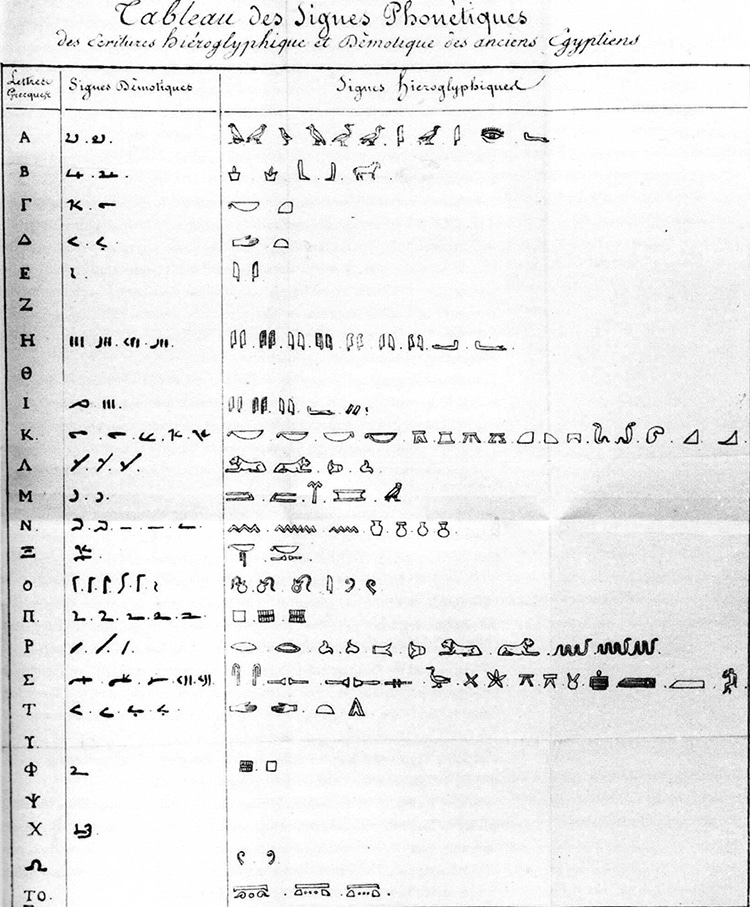

Champollion's table of phonetic glyphs. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain])

Ancient Greek on the Rosetta Stone. (Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0])

Hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone. (Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0])

Demotic script on the Rosetta Stone. (Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0])

To learn more about the Rosetta Stone, check out the British Museum in London or visit their website.

Tourists admire the Rosetta Stone, a famous exhibit at the British Museum, London. (Photo: ProtoplasmaKid via Wikimedia Commons [CC-BY-SA 4.0])

Check out the British Museum for more information on the Rosetta Stone.

Related Articles:

Unearthing the Importance of the Life-Sized Terracotta Warriors

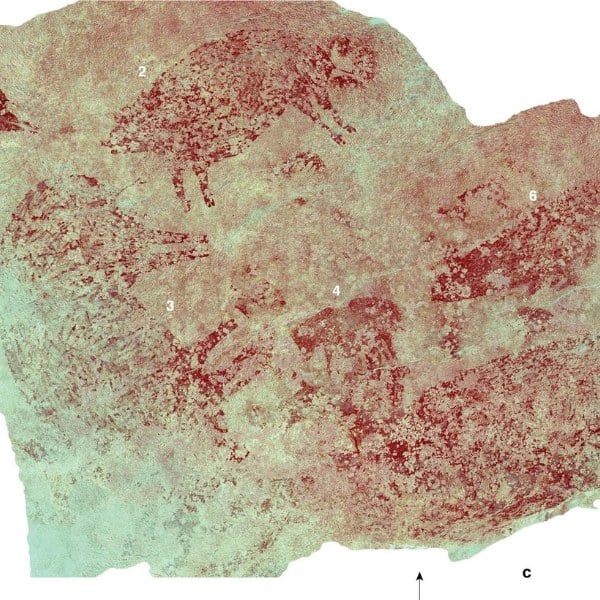

6 Incredible Facts About the Prehistoric Altamira Cave Paintings

10 Facts About the Parthenon, the Icon of Ancient Greece

How This 30,000-Year-Old Figurine Continues to Captivate Today