Photo: Kenneth Dedeu via Shutterstock

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Red is not only one of the primary colors, it's also one of the first colors used by artists—dating back to prehistory. Ranging from orange tinges to deep wine hues, throughout history the color red has held special significance for cultures around the world. The warm color is most commonly associated with love in Western culture and remains an attractive, vibrant color that immediately brings attention to itself.

In many cultures, red symbolizes joy and good fortune. In fact, in many Asian countries brides wear red as a symbol of fertility and luck. In Europe, red became equated with aristocrats and the clergy. Its association with the blood of Christ made it especially important for the Catholic church, so much so that the cardinal was named after the color that Roman Catholic cardinals traditionally wore.

Pervasive in art and textiles since ancient times, the color red is powerful and prestigious. Let's take a look at some of the most important shades of red in art and learn more about the fascinating history of the color red. And if you are looking to go in-depth, Red: The History of a Color is a comprehensive look at all things red.

Red Ochre

A bison from the cave of Altamira in Spain, painted between 15,000 and 16.500 BC.(Photo: National Museum and Research Center of Altamira [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Red was also prominent in ancient China, with early examples of black and red pottery dating between 5000 and 3000 BC. Traces of red ochre were even found on a painter’s palette inside the tomb of King Tut in Egypt.

Fun Fact: In ancient Egypt, red ochre was used as a cosmetic for women to color their lips and cheeks. During celebrations, people would color their bodies with the pigment. In Egyptian culture, red had associations with life, health, and victory. The pigment was also often used in wall paintings.

Cinnabar

Villa of Mysteries, Pompeii. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

This red ranges in hue from brilliant scarlet to deep brick and is named after the mineral from which it’s made. This mercuric sulfide is highly toxic, but has been used since the time of the Egyptians. The brilliant color was favored by Ancient Romans, who used it extensively in decoration. Examples can still be seen in the wall art of Pompeii. In fact, cinnabar was so prized in Roman times that it cost more than Egyptian blue and red ochre from Africa. From the 12th century, cinnabar was also used extensively in carved Chinese lacquerware. In ancient times, vermilion pigments were made from cinnabar. This shouldn’t be confused with later paints also called vermilion.

Fun fact: In Roman times, most cinnabar came from mines at Almadén in Spain. (Unfortunately, the workers were usually prisoners and slaves who were forced to work in the highly toxic environment.)

Cinnabar crystals. (Photo: Albert Russ via Shutterstock)

Vermilion

“Pesaro Madonna,” Titian, 1519-1526. (Photo: WikiArt)

It’s thought that the Chinese were the first to produce synthetic vermilion, perhaps as early as the 4th century BC. The resulting paint, which was brought to Europe by Arab alchemists, was used widely by Renaissance painters, particularly Titian who was known for his layering of the brilliant color. While the pigment is typically an orange-red, one known defect is that it tends to darken over time, becoming a dark purplish-brown. Vermilion remained the most popular red pigment through the 20th century, until its toxicity and expense caused most artists to switch to Cadmium red. In China, vermilion’s importance has caused it to be known as “Chinese red.” The color is thought to be symbolic of life and good fortune and was used to paint temples and the Emperor’s carriage.

Fun fact: In Medieval times, synthetic vermilion was as costly as gold leaf. Thus it was used only for the most important aspects of illuminated manuscripts, while less costly red lead was used for red letters within the text.

The Forbidden City, Beijing. (Photo: Hung Chung Chih via Shutterstock)

Crimson

Coronation mantle of Roger II of Sicily (1133–4), dyed crimson with kermes. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

This strong red color, which leans toward purple, is made from the dried bodies of female kermes. These scale insects, which feed on the sap of evergreen oaks, were harvested commercially to produce dyes and paints. Crimson made out of kermes fell out of favor with the introduction of crimson lake—or carmine—which is produced by the cochineal. This was partly due to the fact that it took twelve times the amount of kermes to achieve the color intensity of the cochineal.

Fun fact: Crimson made from kermes is also called natural crimson to avoid confusing it with crimson lake—or carmine. Later, crimson was also made from Alizarin, the first synthetic red dye. Alizarin crimson paint was a favorite of Bob Ross and was used frequently on The Joy of Painting.

Carmine

“The Jewish Bride,” Rembrandt. 1666. (Photo: Wikiart)

As with all lake pigments, carmine is made from organic matter, as opposed to minerals used in colors like ultramarine or vermilion. Made from cochineal, tiny scale insects that live on cacti, the pigment made its way to Europe in the early 16th century when Spanish conquistadors noticed the brilliant reds used by the Aztecs. Carmine made a beautiful, deep crimson that was used by nearly all of the great 15th and 16th century painters. Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Velázquez are just some of the painters that used carmine to obtain a rich red hue. The pigment must be used carefully, however, as it can change color when exposed to light.

Fun fact: Cochineal insects were a valuable European import in the 16th century, coming in third after gold and silver. Used both in paints and dyes, the resulting color was a symbol of wealth. Many European aristocrats would wear clothing dyed with cochineal, as it produced a red much stronger than the kermes varieties already available in Europe.

Red Lead (Minium)

Red lead, or minium, is another highly toxic material that may have first been manufactured by the Chinese during the Han dynasty. In fact, it’s considered one of the first synthetic pigments, as it’s made by roasting white lead pigment. The longer the white lead was roasted, the more orange-red it would become. Less expensive than pigment made from cinnabar, it was widely used in Medieval manuscripts, as well as Persian and Indian miniature painting.

Vincent van Gogh was known to be a fan of red lead, which he used extensively in his artwork. Unfortunately, minium whitens over time with exposure to light, causing the red in his paintings to fade.

Fun fact: The word “miniature” is derived from minium, as the artisans who worked on Medieval manuscripts were known as miniators.

Complex palace scene, Mir Sayyid Ali, 1539–1543. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Cadmium Red

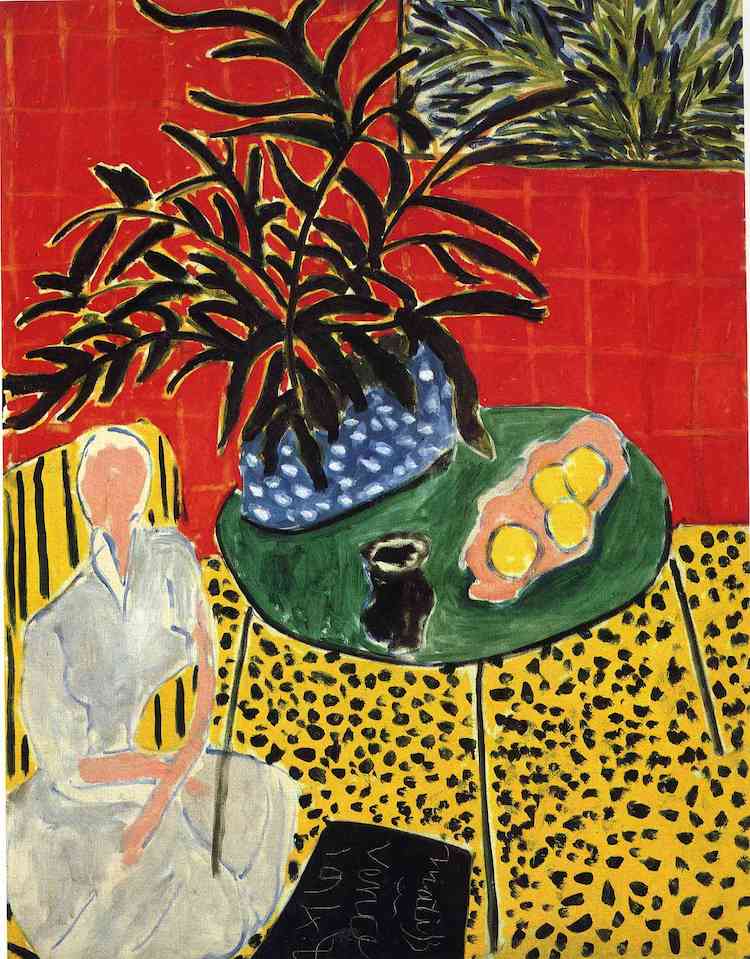

“Interior with Black Fern,” Matisse, 1948. (Photo: WikiArt)

Cadmium red came into favor in the 20th century, becoming commercially available in 1910. The color of natural vermilion, cadmium red is known for its color-fastness. Henri Matisse a particular fan of the brilliantly colored pigment, and was the first prominent painter to use it in his artwork. Though the levels of cadmium sulfide in the pigment are not very toxic, in 2014 the European Union threatened a potential cadmium ban over concerns that it could pollute the water supply when artists cleaned their brushes. Luckily, further research proved that these fears were unfounded and cadmium red continues to remain a beloved member of many artists’ palettes.

Fun fact: Matisse tried, unsuccessfully, to convince Renoir to use cadmium red. Though they were close friends, Renoir quickly switched back to his previous pigment after giving it one try.

Chinese Red

View this post on Instagram

A variety of red tones have been revered in fashion throughout history, but designer Christian Louboutin made one specific shade his color of choice—Chinese Red (not to be confused with vermilion which is also sometimes referred to as Chinese red). In 1992, he unveiled his red-bottomed shoes, which quickly became his brand’s signature style. This very specific color (Pantone 18-1663 TPX) became synonymous with the brand and led Louboutin to trademark his red soles in several countries. Now, the designer’s red-bottomed shoes are seen as a sign of luxury and elegance, often worn by fashion elite and celebrities at highly publicized events. More than merely a color, it has become a symbol of wealth and style.

Fun fact: Louboutin’s signature red soles came about by accident. While working on a prototype, he felt it was missing something. That’s when he noticed an assistant painting her nails red and decided to coat the black sole of the shoes red as well.

Related Articles:

The History of the Color Blue: From Ancient Egypt to the Latest Scientific Discoveries

Curious About Color Mixing? Here Are the Basics You Need to Know

13 Best Watercolor Paint Sets Both Beginners and Professional Artists Will Love

Japanese Designers Create Nameless Paints to Revolutionize How Children Learn about Colors