Copy of a section of “Emperor Minghuang's Journey to Sichuan,” late Ming Dynasty (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

For millennia, silk painting has helped shape China's rich visual history. This exquisite practice pairs two of Chinese culture's most celebrated artistic traditions—sinuous brushwork and tactically spun textiles—making it an exceptionally important craft. Beyond its role as a culture bearer, however, silk painting is prized for its ethereal aesthetic, which artists have continued to adopt and adapt since ancient times. Here, we unfurl the history of this unique art form, from its humble beginnings centuries ago to its contemporary process.

Before tracing the craft's evolution, however, it's important to grasp a basic understanding of the silk painting practice.

What is Silk Painting?

Emperor Huizong of Song “Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk,” ca. 1100-1133(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Silk painting refers to the practice of applying paint to silk textiles. Silk is a fine fiber made from the filaments of silkworm cocoons. When boiled and gently unwound, these pupal casings produce silk strands that can be combined into threads, which, in turn, can be used to make textiles.

How did Chinese artisans traditionally make silk paintings? Historically, practitioners would use a stone to smooth out the surface of the silk. Once primed, the silk was adorned with designs rendered in colorful mineral pigments or black ink (often made from soot and an animal-based adhesive). The latter was mostly used for calligraphy, one of the most important Chinese art forms and earliest incarnations of silk painting.

History

Silk in China

“Pink and White Lotus,” 14th century (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

The earliest known evidence of silk manufacturing in China was found in the soil of a 4th-century-BCE tomb. Located in Jiahu, a Neolithic settlement near the Yellow River, this site has served as a rich source of artifacts since it was rediscovered in 1962. In addition to samples of silk fibroin, a protein, found inside the tomb (and likely the remains of garments used to dress the dead), excavations here have yielded “the earliest playable musical instrument (bone flutes), the earliest mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey and fruit, the earliest domesticated rice in northern China, and possibly the earliest Chinese pictographic writing.”

Written Scrolls

A part of a Taoist manuscript, 2nd century BCE (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Since the Shang dynasty (circa 1600-1100 BCE), calligraphy has been an intrinsic aspect of Chinese culture. Crafted with a brush and ink, calligraphy highlights the understated beauty of handwritten characters through meticulously rendered strokes. A prime example of this art form is a series of hanging banners found in Mawangdui, an archaeological site in Changsha. These manuscripts date back to the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) and were used to document military, medical, and astronomical information.

Calligraphy was rendered on silk (and sometimes bamboo) scrolls until paper—a novel, cheaper material—was invented in the 1st century.

Funerary Paintings

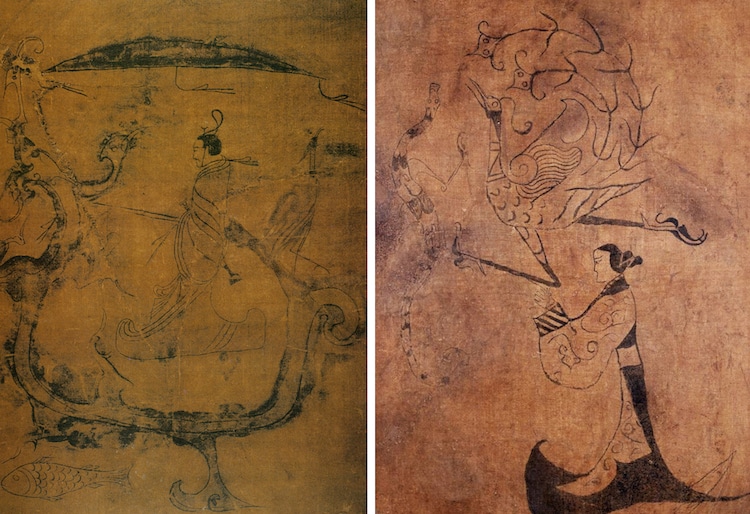

Left: “Silk painting depicting a man riding a dragon”(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain); Right: “Silk painting with a lady, phoenix and dragon”(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In addition to funerary garments and written scrolls, Chinese artisans would soon weave silk textiles for another use: painting. The earliest known examples of this practice are tomb paintings from the Warring States Period, including two national treasures: Silk painting depicting a man riding a dragon and Silk painting with a lady, phoenix and dragon. These pieces were both discovered in tombs in Changsha and were created between 475 and 221 BCE. Each painting features a side-profile portrait (of a male and female figure, respectively) rendered in black brushstrokes reminiscent of calligraphy.

The pieces served the same function: to aid the dead as they cross into the afterlife. “During the funeral procession, [each] painting was held up in front of the coffin, which was said to bring comfort and calmness to the soul of the deceased.”

The Gongbi Technique

Qian Xuan, “Early Autumn,” 13th century (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Over the succeeding centuries, Chinese artisans would continue to create silk paintings. Soon, however, they moved beyond simple black-ink designs and started painting compositions in the Gongbi style.

Gongbi, or “meticulous painting,” is renowned for its vibrant color palette, realist details, and figurative subject matter. This approach to painting reached peak popularity between the 7th and 13th centuries, culminating in a wealth of beautifully rendered handscrolls. During this time, its influence reached Japan, India, and even Western Europe, where painted silk fabric could be found “draped over altars or fashioned into curtains.”

Over the next few centuries, silk painters would continue to employ the Gongbi technique, whose emphasis on detail lent itself particularly well to handscrolls. “In unrolling the scroll, one greets a remembered image with pleasure,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains, “but it is a pleasure that is enhanced at each viewing by the discovery of details that one has either forgotten or never noticed before.”

Contemporary Silk Painting

View this post on Instagram

Since the Middle Ages, the silk painting tradition has continued to proliferate. While the process of creating a silk painting has evolved, employing the delicate fiber as a canvas still calls for a special process. Today, this often includes stretching and dying the textile before outlining a design in gutta, a latex-like coating made from the sap of gutta-percha trees, to the surface of the silk. The gutta acts as a barrier, giving form to the painting and preventing the paint from bleeding. Once the gutta is dry, paint can be applied. After the paint, too, has dried, the gutta is removed, culminating in bold, crisp blocks of color—and the prolonging of a legacy.

Related Articles:

Origami: How the Ancient Art of Paper Folding Evolved Over Time and Continues to Inspire

What is Ebru Art? Exploring the Ancient Techniques of “Painting on Water”

Artist Uses Handcrafted Silk Shoes as Canvas for Traditional Chinese-Style Illustrations

Kirigami: The Ancient Art of Paper Cutting and How Artists Are Keeping It Alive