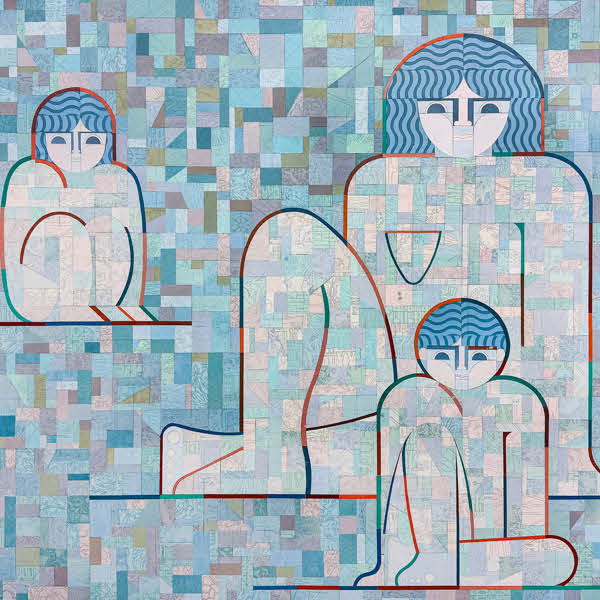

A reconstruction drawing of the Iron Age grave of a nonbinary individual. (Photo: Veronika Paschenko/University of Turku)

In 1968, workers digging to lay a water pipe discovered a bronze sword handle. This led to the reveal of a 900-year-old grave at the work site in Suontaka Vesitorninmäki, Hattula, Finland. Inside the grave was an Iron Age individual dressed in women's clothing. The person's burial with a sword confused researchers. Was this an unusual warrior woman, or a double grave of a couple? Now, with the help of modern DNA analysis, researchers believe the grave may be that of a nonbinary individual who held high status in their Dark Ages Scandinavian community.

DNA analysis of the buried warrior was not available when the grave was discovered. However, a modern team from Finland and Germany sequenced what is salvageable of the ancient genetics. They published their findings in the European Journal of Archeology. While they cannot be 100 percent certain, the team strongly believes the individual had Klinefelter syndrome. Individuals with Klinefelter syndrome are born with an extra chromosome. Most males carry an X and a Y chromosome, with the X inherited from their mother and the Y from their father. Most females have two X chromosomes, one from either parent. However, combinations other than these two can occur.

People with Klinefelter syndrome carry two X chromosomes and a Y chromosome. This occurs in 1 in every 660 males according to Britain's National Health Service. Many people with Klinefelter syndrome are assigned male at birth, have male anatomy, and may never even know they carry an extra chromosome. However, the extra X can cause some health effects, including lower testosterone, undescended testes, and enlarged breasts. For this reason, the ancient individual may have presented secondary sex characteristics associated with both men and women.

“If the characteristics of the Klinefelter syndrome [were] evident on the person, they might not have been considered strictly a female or a male in the Early Middle Ages community,” said Doctoral Candidate of Archaeology Ulla Moilanen from the University of Turku. However, people with Klinefelter syndrome can hold any of many gender identities. Therefore, it is not the DNA but the burial items which suggest a nonbinary identity. The women's clothing, combined with the two swords, jewelry, and rich furs all suggest an elite individual who was respected within the community. Women were not typically buried with weapons, nor were men in Scandinavia typically buried in women's clothing. This makes the discovery of a nonbinary burial important for understanding Scandinavian notions of gender.

According to The Smithsonian Magazine, the nonbinary individual buried at Suontaka is not the only evidence of nuanced gender identities in medieval Scandinavia. The male gods themselves took on a certain female nature when performing certain magic. Certainly, the possibilities for future research into medieval Scandinavian gender identities through literature and archeology are quite exciting and necessary.

A burial of a warrior in women's clothing discovered in 1968 is now thought to be an individual who occupied a nonbinary identity.

According to the newly-published study, the famous sword of Suontaka has been hidden in the grave at a later point in time. (Photo: The Finnish Heritage Agency, CC BY 4.0)

h/t: [NPR, The Smithsonian]

Related Articles:

Archeologists Accidentally Discover 250 Rock-Cut Tombs in Egypt

Archaeologists Discover “Little Pompeii” in Southern France

3,000-Year-Old Egyptian Mummies Found Inside 30 Well-Preserved Coffins

Explore the Fascinating History of Petra, a Once-Lost City That’s Now a Wonder of the World