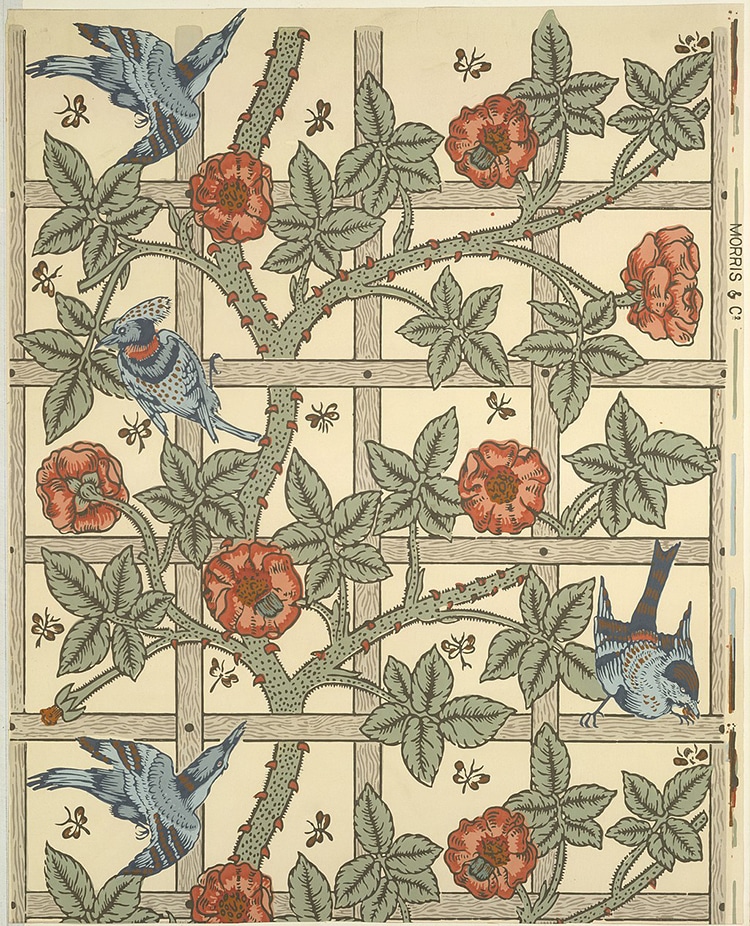

“Strawberry Thief” 1883 via Wikimedia Commons

Elegant swirls of vines, flowers, and leaves in perfect symmetry, William Morris’ iconic patterns are instantly recognizable. Designed during the 1800s, Morris’ woodblock-printed wallpaper designs were revolutionary for their time, and can still be found all over the world, printed for furniture upholstery, curtains, ceramics, and even fashion accessories. But do you know the history of how they came to be?

The Arts and Crafts Movement

Beginning in Britain around 1880, the Arts and Crafts movement was born from the values of people concerned about the effects of industrialization on design and traditional craft. In response, architects, designers, craftsmen, and artists turned to new ways of living and working, pioneering new approaches to create decorative arts.

One of the most influential figures during this time was William Morris, who actively promoted the joy of craftsmanship and the beauty of the nature. Having produced over 50 wallpaper designs throughout his career, Morris became an internationally renowned designer and manufacturer. Other creatives such as architects, painters, sculptors and designers began to take up his ideas. They began a unified art and craft approach to design, which soon spread across Europe and America, and eventually Japan, emerging as its own folk crafts movement called Mingei.

Who was William Morris?

Full Name | William Morris |

Born | March 24, 1834 (Walthamstow, England) |

Died | October 3, 1896 (Hammersmith, England) |

Notable Artwork | Wallpaper and textile design |

Movement | Arts and Crafts |

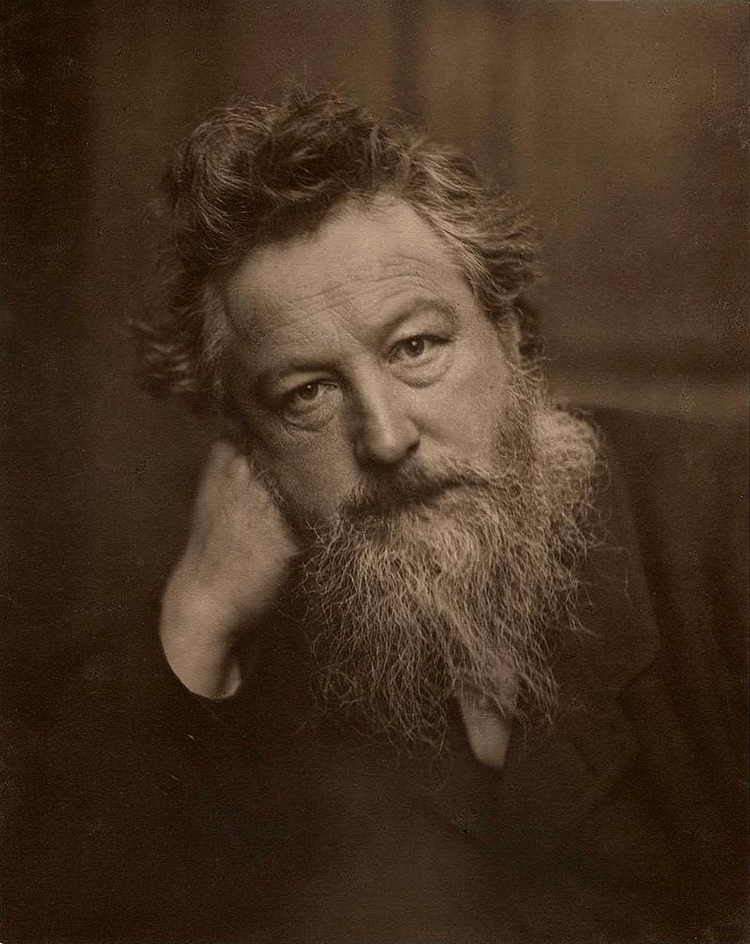

Born in Walthamstow, East London in March 1834, William Morris was a poet, artist, philosopher, typographer, political theorist, and arguably the most celebrated designer of the Arts & Crafts movement. He strived to protect and revive the traditional techniques of handmade production that were being replaced by machines during the Victorian era's Industrial Revolution. Although he dabbled in embroidery, carpet-making, poetry and literature, he mastered the art of woodblock printing, and created some of the most recognizable textile patterns of the 19th century.

Portrait of William Morris by Frederick Hollyer via Wikimedia Commons

Born into a wealthy middle-class family, Morris enjoyed a privileged childhood, as well as a sizable inheritance, meaning he would never struggle to earn his own income. He spent his childhood drawing, reading, and exploring forests and grand buildings, which triggered his fascination with natural landscapes and architecture.

Having developed his own particular taste from a young age, he began to realize the only way he could have the beautiful home he wanted was if he designed every part of it himself. As he famously once said, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.”

The Red House

While studying at Oxford, Morris met his lifelong friend, architect Philip Webb. His dear friend helped him design and construct his Medieval-inspired, Neo-Gothic style family home in Bexleyheath, where he lived with his wife, Jane Morris, and his two children, Jane “Jenny” Alice Morris and Mary “May” Morris. Built in 1860, it became known as the Red House, and is now one of the most significant buildings of the Arts and Crafts era. Today, the house is owned by the National Trust and is open to visitors.

The “Red House,” home of William Morris. via Wikimedia Commons

A number of Morris’ creative friends spent a lot of time at the Red House, including Pre-Raphaelite painters Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who both helped him elaborately decorate the abode. While he envisioned living there for the rest of his life, Morris’ perfectionism caused him to move on after only five years. Over the course of his short stay, he discovered a number problems with the property. However, he enjoyed the process so much that he decided to set up his own design company, with a desire to create affordable “art for all.”

Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. which was later known as simply Morris & Co., was incredibly successful, and produced reams of fabric and wallpaper designs for over 150 years.

The Red House front door from inside. Photo: Tony Hisgett (CC BY 2.0) via Wikimedia Commons

Morris’ Wallpaper Designs

Featuring swirling leaves, thieving birds, rose-filled trellises, and fruit tree branches, the designs of William Morris have a unique timeless quality. He began designing wallpapers in 1862, but their sale was delayed by several years while he experimented with printing from zinc plates.

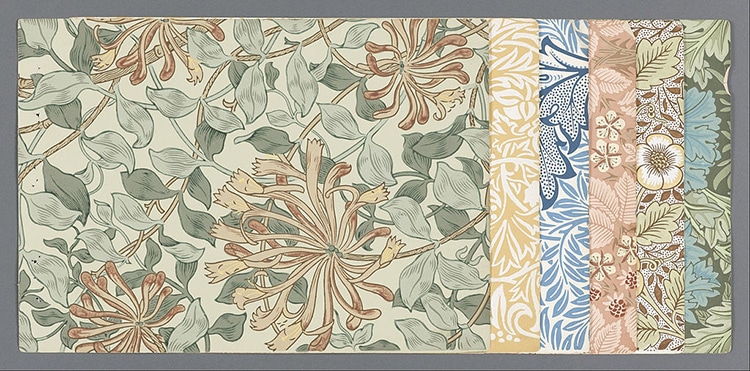

Morris & Co. sample book via Wikimedia Commons

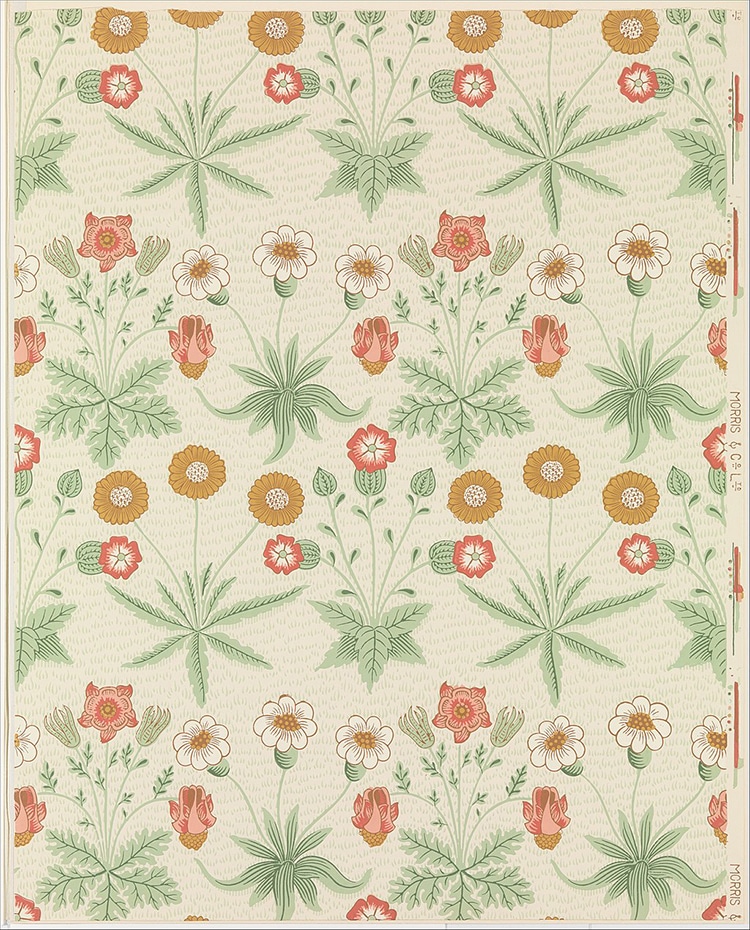

Inspired by nature, Morris’ designs feature leaves, vines, and flowers that he observed in his gardens or on walks in the countryside. Rather than life-like illustrations, his drawings are subtly stylized versions. Daisy, a simple design featuring meadow flowers, was the first of Morris’ wallpaper designs to go on sale in 1864.

“Diasy” 1864 via Wikimedia Commons

Morris designed Trellis after being unable to find a wallpaper that he liked enough for his own home. Inspired by the rose trellis in the garden of the Red House, Morris designed the pattern which went on sale in 1864. Interestingly, Morris could not draw birds, and the birds for this design were actually sketched by Philip Webb, the same friend and architect who designed the Red House.

William Morris design for “Trellis” wallpaper 1862 via Wikimedia Commons

“Trellis” wallpaper designed by William Morris 1862 and first produced in 1864. Via Wikimedia Commons

Morris had his wallpapers printed by hand, using carved, pear woodblocks loaded with natural, mineral-based dyes, and pressed down with the aid of a foot-operated weight. Each design was made by carefully lining up and printing the woodblock motifs again and again to create a seamless repeat. Morris once spoke about the precise process, saying, “Remember that a pattern is either right or wrong. It cannot be forgiven for blundering, as a picture may be which has otherwise great qualities in it. It is with a pattern as with a fortress, it is no stronger than its weakest point.”

He employed the printers Jeffrey & Co. to print his wallpapers up until his death in 1896, when the Merton factory took over production until the company’s voluntary liquidation in 1940.