“Hope Amidst the Ashes” by Jo-Anne McArthur. Grand Prize Winner.

Bushfires have ravaged the Australian landscape in recent years, burning some 17 million hectares (42 million acres) in 2019 and 2020 alone. Driven by record-setting droughts and temperatures, wildfires have devastated habitats and wildlife populations alike, and scientists are worried that these events will only grow more common with climate change. Despite the sobering trend, conservationists remain committed to protecting the places and species that make this island nation unique.

In January of last year, shortly after a devastating bushfire near Australia’s southeast coast, photographer Jo-Anne McArthur accompanied one such effort, as a team from an organization called Vets for Compassion searched a eucalyptus plantation for injured and starving koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus). There she encountered this female eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), a joey in her pouch, that had somehow survived the cataclysm. For McArthur, it was a powerful moment: two of Australia’s most iconic species—the kangaroo and the eucalyptus tree—standing at a worrisome crossroads in their history. But the individuals in her frame were also symbols of hope, that life can persist against all odds.

Each year, the California Academy of Sciences asks photographers to submit their best photos to showcase the Earth's biodiversity. The winners and finalists of the 2021 BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition highlight the beauty of nature, as well as its struggles. Originally appearing in bioGraphic, the winning photographs are a sight to behold.

Photographer Jo-Anne McArthur won the grand prize for her photo Hope Amidst the Ashes. McArthur took the photo while accompanying Vets for Compassions as the organization searched for koalas injured in the Australian bushfires. Surrounded by the burnt forest, a female eastern grey kangaroo stands proud with her joey tucked safely into her pouch. This powerful moment of survival is a metaphor for the resilience of the entire country and shows that we should still have hope even against all odds.

The other winners and finalists are spread across several categories like Aquatic Life, Art of Nature, Winged Life, and Terrestrial Life. The images are a cross-section that takes us from the Yukon to the tropical seas of Palau. By spotlighting these incredible photographs of the natural world, the organizers hope that people will be inspired to protect and conserve the diversity of life found on our planet.

These images originally appeared on bioGraphic, an online magazine about science and sustainability and the official media sponsor for the California Academy of Sciences' BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

See more winners and finalists from the 2021 BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

“Facing Reality” by Amos Nachoum. Aquatic Life Finalist.

With their silky coats, big, dark eyes, and perpetual grins, leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) can look downright cuddly lounging on Antarctic ice floes. It’s safe to say, though, that penguins have a different perspective of these powerful apex predators. Weighing up to 600 kilograms (1,320 pounds), with powerful jaws lined with sharp teeth, and long front flippers that propel them through the water at speeds up to 37 kilometers per hour (23 miles per hour), leopard seals are capable of catching and subduing a wide range of prey. Few animals are safe in their presence. Studies have shown that leopard seals feed on everything from krill, fish, octopuses, and crabs to penguins and other seals. A recent study conducted on the Antarctic Peninsula, not far from where photographer Amos Nachoum captured this image of a leopard seal preying on a young Gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua), found that penguins make up about a quarter of the leopard seal’s diet throughout the year. That proportion increases to nearly 50 percent for the larger female leopard seals, especially when they have pups. As polar regions continue to warm disproportionately to the rest of the world, scientists are scrambling to better understand such feeding behaviors and their potential to impact the populations of vulnerable species.

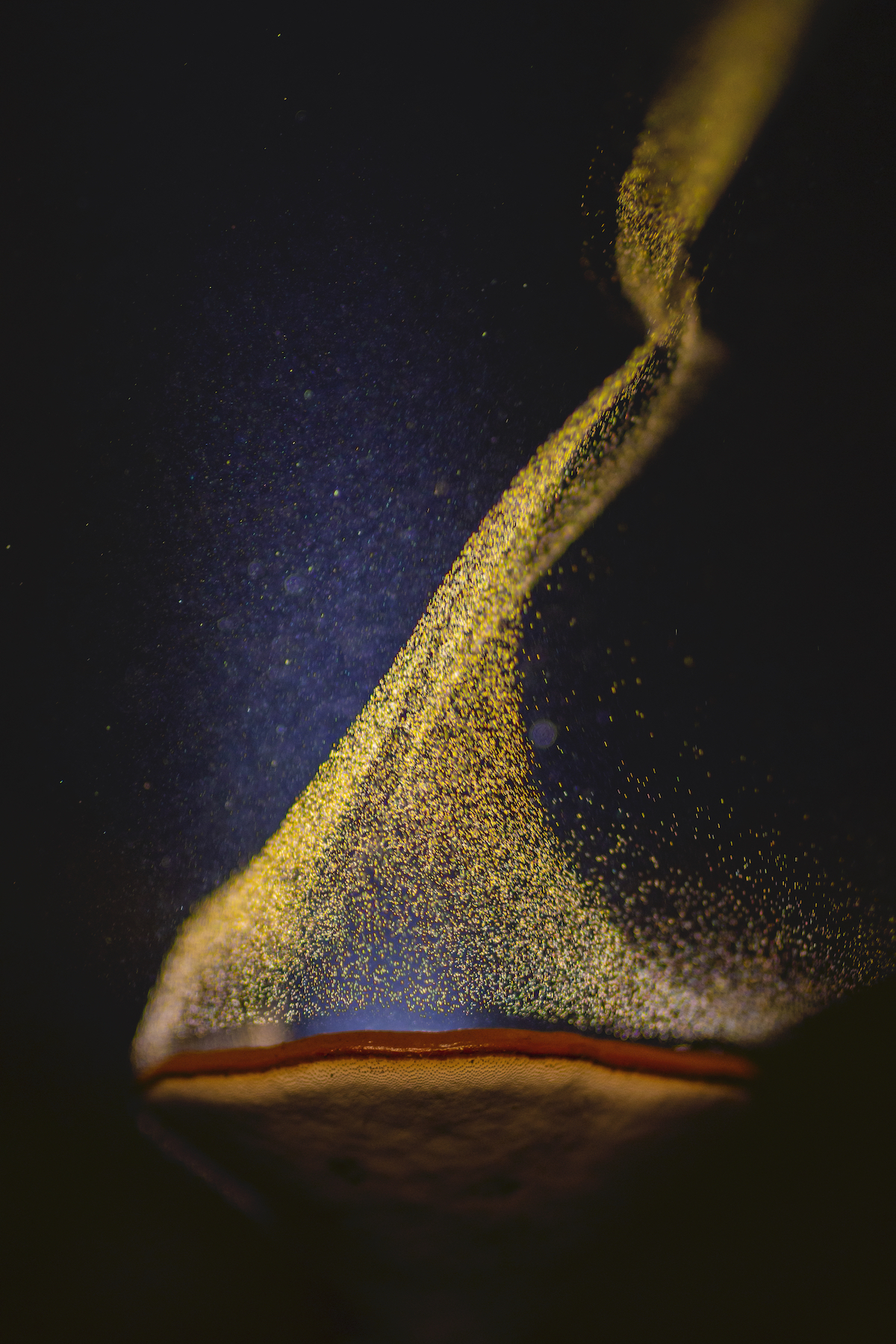

“Rain Dance” by Sarang Naik. Art of Nature Winner.

Dancing in the glow of photographer Sarang Naik’s flashlight, a golden plume of spores rises from the gills of a mushroom cap outside of Toplepada, India. In due time, this magical pixie dust will create more mushrooms—and not only in the way that you might think. While a small number of these mighty motes will land on soil suitable enough for producing the branching underground filaments that beget new mushrooms, many more spores will find their way into the atmosphere to serve an equally important purpose. Each year, millions of tons of fungal spores are aerosolized into the atmosphere where they provide the solid core for the condensation of water into clouds and rainfall, breathing life into forests around the world and sustaining future generations of fungi. This cycle can go both ways, however. As droughts worsen with climate change, fewer mushrooms will spring up, which in turn lessens spore-spurred rains, which may then lead to more intense droughts in the future.

“Taking a Load Off” by Nicolas Reusens. Winged Life Finalist.

While there’s no particular shortage of perches in the Ecuadorian highlands, few seem as tailor-made for little feet as the long, slender beak of a sword-billed hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera). What might appear to be a youngster taking a break under the exasperated gaze of its parent, turns out to be a bird of a different feather: an opportunistic speckled hummingbird (Adelomyia melanogenys) simply looking to save a little energy. For hummingbirds, especially species that live in the cool and wet Andean cloud forests like these two, calories—those they consume and those they conserve—are key to survival and reproduction. After all, tiny though they are, it can take hundreds of flower visits per day to keep a hummingbird running. So, a conveniently placed perch, and one that comes with its own predator-detection capabilities, is hard to pass up.

“Boss” by Michelle Valberg. Terrestrial Life Winner.

On a remote island in northern British Columbia, photographer Michelle Valberg crouched low to the ground, trying to remember to breathe. Several meters in front of her, a Kermode bear (Ursus americanus kermodei)—a subspecies of the American black bear—had plunged its head into a river in search of salmon roe, and she knew what would likely happen next. When the large bear needed a breath, he pulled his head out of the water and shook, sending sparkling droplets of water spiraling around his head.

While most of the Kermode bears that roam the region’s coastal islands are black, about 10 to 25 percent are white. This distinctive coloring is not an albino condition, since the bears have pigmented skin and eyes. It is, however, an inherited trait that is fully recessive, and scientists had long wondered why white-morph bears—often called spirit bears or ghost bears—were so common on the islands. In 2009, a team of researchers from the University of Victoria monitored salmon fishing proficiency among both black and white Kermode bears and found that while black bears were slightly more successful when fishing at night, white bears were significantly more successful during the day. Spirit bears, like the one Valberg photographed, are highly conspicuous from a human standpoint, but this is not the case for a salmon looking up through the water. Against a bright sky, a white predator is actually less conspicuous than a dark one, which is why so many seabirds and waders have white plumage.

On this particular day, the bear in front of Valberg could have been any color; the roe that lined the rocks on the riverbed made an easy meal. Relaxed and confident, he briefly made eye contact with Valberg before lowering his head back into the water. “I felt a catch in my throat,” she says of that moment, which encapsulated what wildlife photography means to her: the opportunity “to look into the eyes of the wild and see ourselves reflected, to understand that we are, after all, intrinsically entwined.”

“Sign of the Tides” by Ralph Pace. Human/Nature Winner.

Though a post-pandemic world is finally in sight, the scars of COVID-19 will live on for years to come—including those on our environment. Since the start of the pandemic, the production of single-use plastics has skyrocketed, largely driven by the surge in epidemiologically necessary but ecologically devastating personal protective equipment. According to one study, 129 billion face masks and 65 billion gloves were used globally each month during the pandemic, as much as 75 percent of which are likely to end up in landfills or the ocean. Much of that equipment—including this mask being investigated by a curious California sea lion (Zalophus californianus)—is made from durable plastics that take hundreds of years to break down. However, if the past year has shown us anything, it is that all can be accomplished through resources and resolve. Perhaps a new picture of our approach to single-use goods will soon emerge.

“Another Planet” by Fran Rubia. Landscapes, Waterscapes, and Flora Winner.

What looks at first glance to be lava flowing down the sides of these Icelandic volcanoes is, in fact, iron oxide deposited during past eruptions. Unlike Geldingadalir, a volcano just 20 minutes away from Reykjavík that has been actively erupting since March 19, 2021, the last eruption here in Fjallabak Nature Reserve took place in 1480.

The climate in the reserve is arid and cold, and the growing season is limited to about two months a year, so vegetation is scarce, and mineral-streaked mountains provide the landscape with much of its color. Photographer Fran Rubia was awed by its stark beauty, especially when he first saw it from above. “When I lifted the drone for a reconnaissance flight, I was surprised by the large amount of iron oxide inside the volcanoes,” he says. The photograph he captured later that day made him reflect on the importance of preserving such places. “Because the image seems to be photographed in another world, on another planet, it seemed to me a primal place without any human alteration, which made it even more special.”

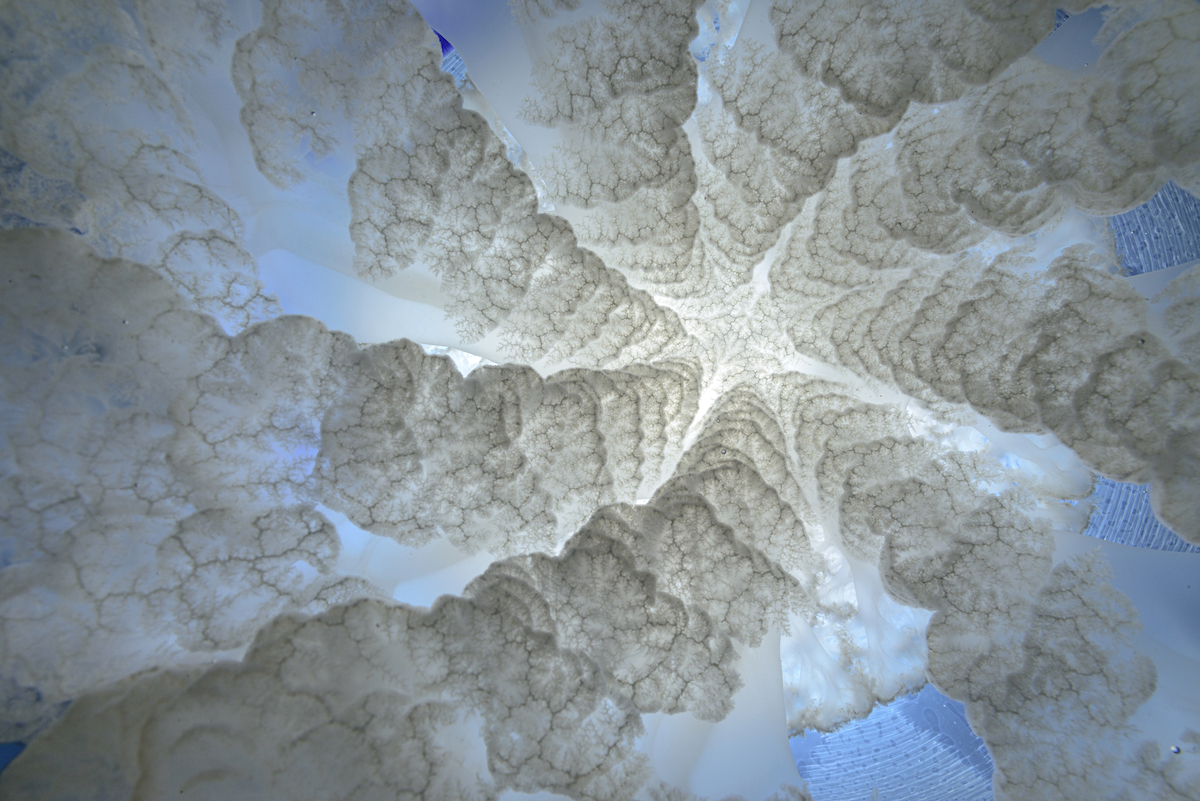

“Down the Hatch” by Angel Fitor. Art of Nature Finalist.

This beautiful and mesmerizing view may very well be the last thing that many hapless ocean-going creatures see before falling victim to the barrel jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo). Also known as the dustbin-lid jellyfish for the size and shape of its bell when washed up on UK shorelines, the species is one of the largest jellies in the world, reaching 90 centimeters (35 inches) or more in diameter. It ranges widely from the North and South Atlantic to the Mediterranean and Black Sea. While most often seen dead and flattened on beaches, in the water, the barrel jellyfish’s translucent bell takes on a mushroom shape, fringed with a brilliant violet ribbon of sensory organs. Eight frilly arms trail behind the bell, subduing prey and pulling it toward the jellyfish’s mouth. By backlighting his shot, photographer Angel Fitor was able to capture those arms here in intimate and ominous detail.

“Beak to Beak” by Shane Kalyn. Winged Life Winner.

Common ravens (Corvus corax) usually mate for life, and this intimate, open-beaked moment captured by photographer Shane Kalyn is likely an example of allopreening—reciprocal grooming that serves both to solidify social bonds and to keep plumage clean. Tender as this behavior is, it sometimes puts the birds at risk of an aggressive intervention from other members of their species. A 2014 study by scientists at the University of Vienna revealed that ravens will often interrupt grooming sessions between other paired individuals, especially those with more tenuously established bonds. These interventions are an apparent attempt to prevent neighboring couples from developing the kinds of strong pair bonds that lead to greater reproductive success. As scientist Kaeli Swift notes, “embracing the results of this study requires accepting the idea that an animal, especially a bird, is capable of putting future rewards ahead of current risk or losses. As humans, this kind of future planning is an ability we take for granted, but it’s quite a cognitive feat.” For birds with a documented ability to use tools and solve puzzles, it’s just one more impressive feat to add to the list.

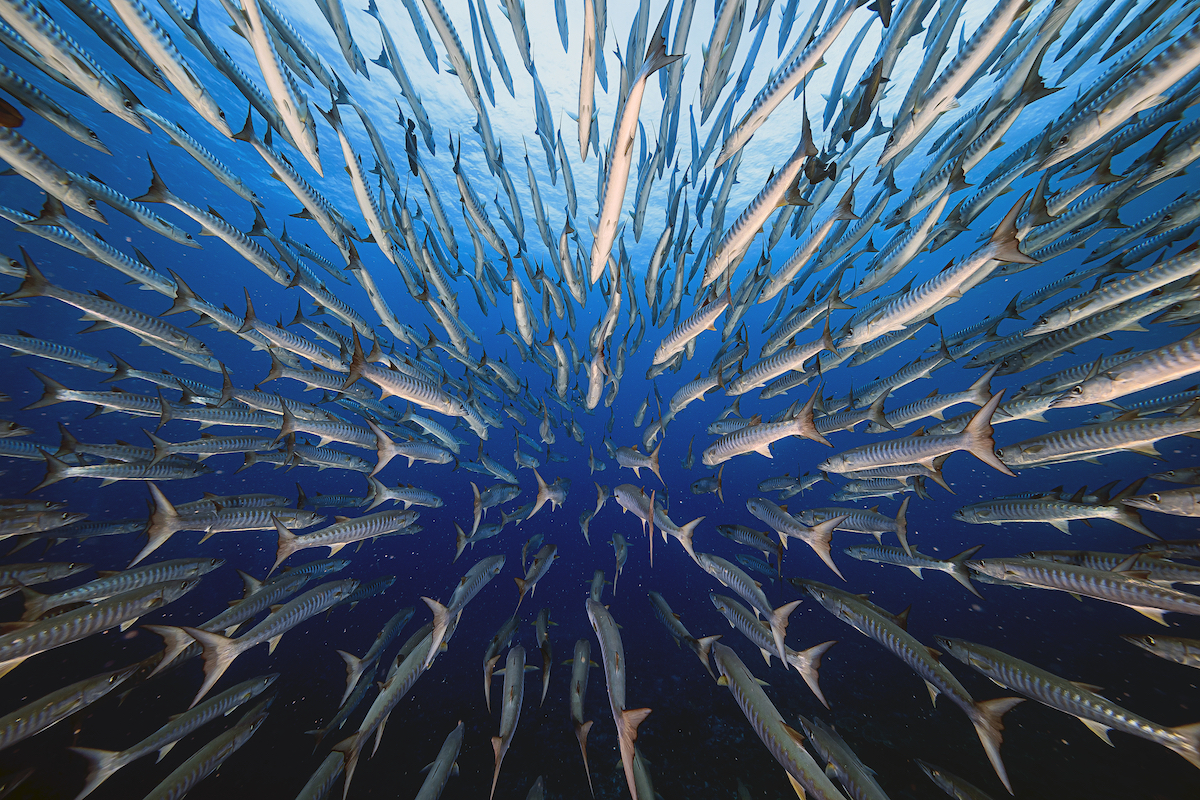

“New Kid in School” by Yung-Sen Wu. Aquatic Life Winner.

With mountainous reefs, more than a thousand species of tropical fish, and several species of coral-dwelling sharks, Palau’s Blue Corner, located about 40 kilometers southwest of Koror, is considered one of the best dive sites in the world. But beholding its beauty is no mean feat. Unpredictable currents that change speed and direction at a moment’s notice can zap even the most experienced diver’s energy and send them hurtling towards the reef or out to sea.

Given these turbulent conditions, it’s hard to imagine that underwater photographer Yung-Sen Wu didn’t feel a tinge of jealousy at the effortless swimming of the streamlined barracuda (Sphyraena sp.) he was there to photograph. Known more for their hunting prowess than their hospitality, the barracuda were slow to acclimate to Wu’s presence. Over the course of five days, however, Wu braved the Blue Corner’s currents daily in an effort to gain their trust, finally being allowed into the school on his last day there to capture this striking image.

“Ice Bears” by Peter Mather. Photo Story Winner (one of six images).

In Canada’s Yukon Territory, grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) delay their hibernation to catch the last salmon runs of the season. As temperatures drop below -20 degrees Celsius, the grizzlies’ water-soaked fur freezes into a chandelier of icicles that jingle with each step. Local Indigenous peoples tell stories of arrows unable to penetrate the icy armor of the bears. Unfortunately, Yukon’s ice bears, as they are known, are facing new threats for which their armor is no match. Climate change and other human activities are leading to sparse salmon runs, reduced river flows, and shorter winters, all of which put the ice bears’ way of life in jeopardy.

“Nutritional Supplement” by Nick Kanakis. Landscapes, Waterscapes, and Flora Finalist.

Despite its modest proportions and rarity in the wild, the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) is one of the most recognizable plants in the world—its iconic form more than simply suggestive of the flytrap’s carnivorous potential. That role reversal, a plant that eats animals, has become a popular novelty for many people, driving a lucrative market in cultivated plants—and sadly, the poaching of wild ones as well. In its native longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests of the Carolinas, however, carnivory is a means of survival. There, the species makes its living much like other plants, harnessing energy from sunlight to make its food. In contrast to many other plants, however, the Venus flytrap must also catch vital nutrients that are missing from the soils in which it grows. With hinged leaves that snap shut at the slightest touch of hair-like triggers on their surfaces, it’s highly specialized to do just that, as this hoverfly (Toxomerus sp.) going about its business in a North Carolina forest last November learned the hard way.