Throughout an artist's lifetime, changes in approach, subject matter, and even style are to be expected. This phenomenon is apparent in the evolution of modern art‘s most beloved painters, from Monet‘s move toward abstraction to Van Gogh‘s brightened color palette. Though prevalent among most master painters, it is particularly emphasized in the paintings of Spanish artist Pablo Picasso.

With an artistic career that spanned 79 years and included success in painting, sculpture, ceramics, poetry, stage design, and writing, his tendency to experiment with his craft is unsurprising. However, the extent to which his style changed in each discipline—particularly, in painting—is unlike that of any other artist. Therefore, to trace his stylistic evolution, his body of work is often divided into periods: early work, the Blue Period, the Rose Period, the African Period, Cubism, Neoclassicism, Surrealism, and later work. Taken together, it's easy to see why he was one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Here, we explore these changes, beginning with a phase that is often widely overlooked and even entirely unknown: Picasso's roots in realism.

Early Work

Pablo Picasso was born in Málaga, Spain, in 1881 to two artistic parents. From an early age, his father taught him formal drawing techniques, culminating in a mastery of oil painting when he was just eight years old.

At the young age of 13, Picasso began his career as an artist. At this time, he worked in a realist style; he depicted subjects authentically and employed a true-to-life color palette. He particularly enjoyed painting scenes inspired by his Catholic faith and portraits of his family members.

This traditional, academic approach is evident in his church-inspired paintings and his portrayals of loved ones, like The Altarboy and Portrait of the Artist's Mother.

The Altarboy (1896) (Photo: Wiki Art)

Portrait of the Artist's Mother (1896) (Photo: Wiki Art)

From 1897, however, Picasso's paintings took on a less lifelike quality. Undoubtedly influenced by Expressionist Edvard Munch and Post-Impressionist painter Toulouse-Lautrec, these pieces—like The Artist's Sister Lola—convey Picasso's growing interest in experimenting with a more freeform, avant-garde style.

“The world today doesn't make sense,” Picasso famously said, “so why should I paint pictures that do?”

The Artist's Sister Lola (ca. 1899-1900) (Photo: La germana de l'artista, Lola © 2011 by Lluís Ribes Mateu (photographer), CC BY-NC 4.0)

Blue Period (1901-1904)

In 1901, Picasso appeared to have entirely abandoned realism. This is particularly clear in his preference for color, which evolved from naturalistic hues to cooler tones. This change in pigment lasted until 1904, and is now characterized as the artist's Blue Period.

Art of this period is somber in both color and in subject matter—an approach likely caused by depression due to a close friend's suicide. The monochromatic pieces often feature the human condition, with figures living in poverty or despair, like the gaunt guitar player in The Old Guitarist, the unhappy Absinthe Drinker who sits with her arms folded, and the embracing Mother and Child who actually live in a disease-ridden women's prison.

The Old Guitarist (ca. 1903-1904) (Photo: Coldcreation via Wikipedia)

The Absinthe Drinker (1901) (Photo: Buveuse d'absinthe (Absinthe Drinker), 1901 © 2023 by B (photographer) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Mother and Child (1901) (Photo: Mother and Child © 2017 by Helena (photographer), CC BY 4.0)

Picasso's Blue Period (and causal depression) lasted until 1904. At this time, less solemn subjects and a warmer color scheme began to pop up in his paintings.

Rose Period (1904-1906)

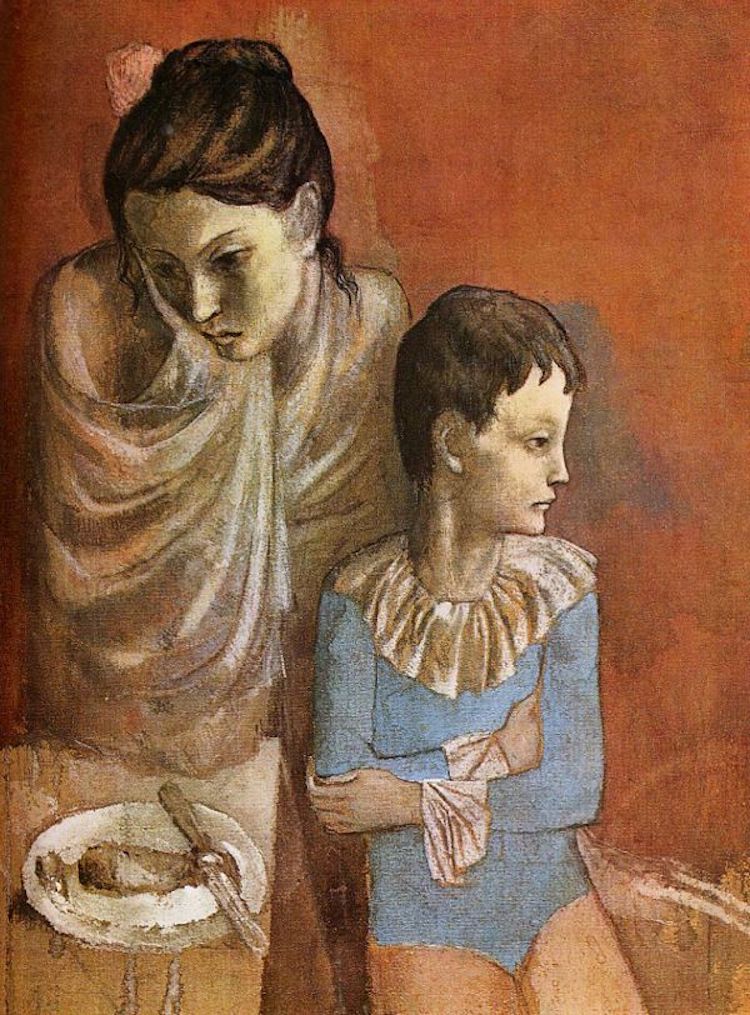

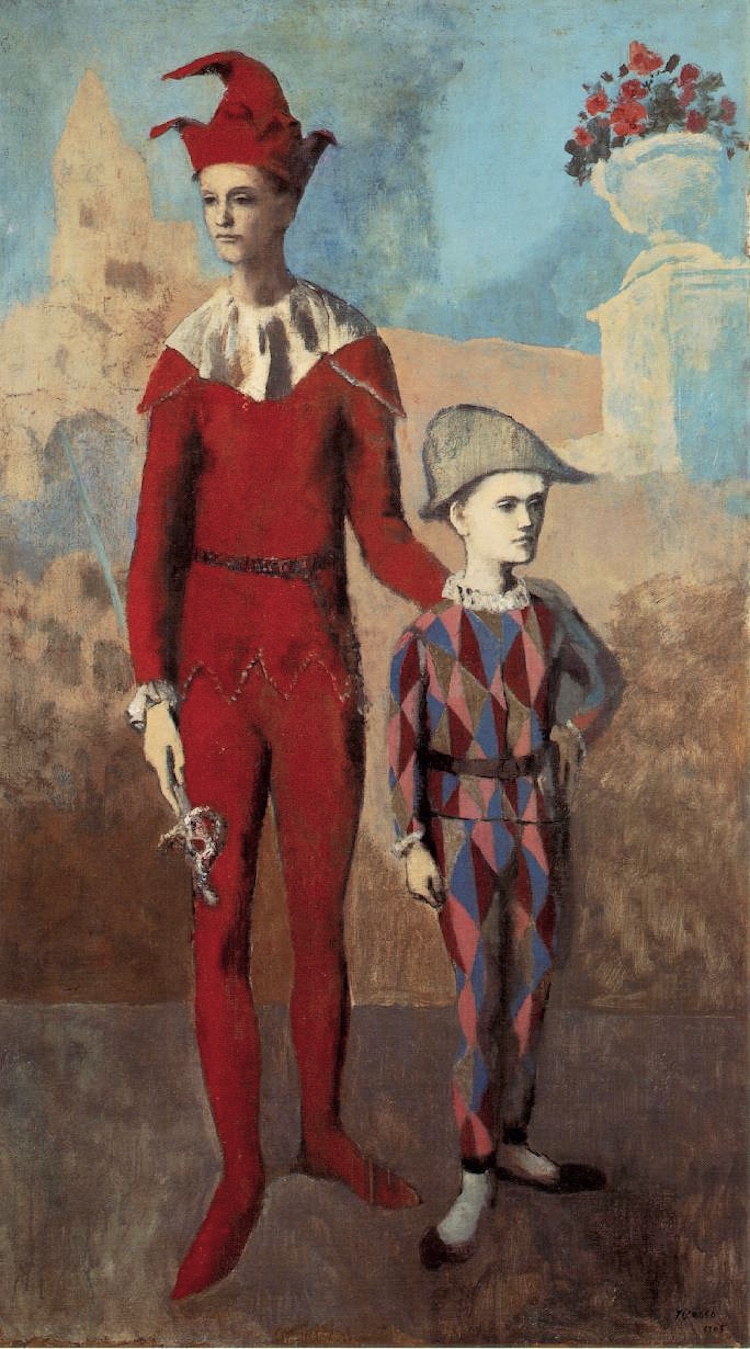

As Picasso transitioned to his Rose Period in 1904, he continued to depict figures in his characteristically painterly style. While blue tones are still present in these paintings, they are contrasted by warmer shades. Similarly, after moving to Montmartre, a Bohemian district in Paris, he shifted his focus from individuals living in despair to entertainers, including harlequins, acrobats, and other circus performers.

Acrobat and Young Harlequin (1905) (Photo: UGA via Wikipedia, Public domain)

The Actor (ca. 1904-1905) (Photo: Wikipedia, Public domain)

At this time, Picasso began to experiment with Primitivism, a style that he would eventually embrace in 1906.

African Period (1906-1909)

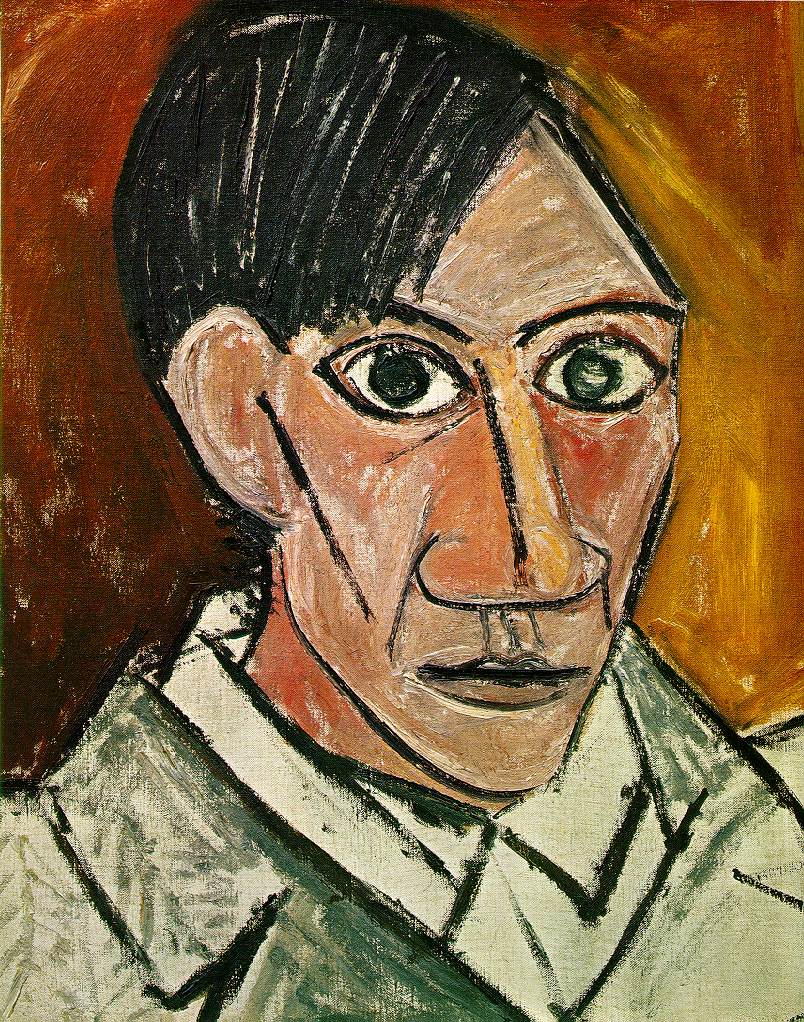

For the three years that followed his Rose Period, Picasso found inspiration in Oceanic and African art. Known as his African Period, this phase retained the warmth of his Rose Period but conveyed a shift in both style and subject matter. Rather than produce figurative portrayals of performers, he began to depict abstracted, African mask-inspired depictions of all sorts of figures, from sex workers in a Barcelona brothel (Les Demoiselles d'Avignon) to the artist himself (Self-Portrait).

Picasso's fascination with the simplification and fragmentation found in “primitive” art inspired his next—and arguably most famous—phase: Cubism.

Cubism (1908-1914)

Cubism is a genre that features subject matter broken down into fractured forms. Pioneered by both Picasso and Georges Braque and renowned as one of the most important art movements, Cubism is separated into two primary phases: Analytical and Synthetic.

Analytical (1908-1912)

Analytical Cubism dominated the first four years of the movement. It is characterized by monochromatic, topsy-turvy canvases full of overlapping, geometric forms. The arrangement of these fragments form the subject, which is often unrealistically depicted from multiple angles at once.

Girl with a Mandolin (1910) (Image: MoMA via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Synthetic (1912-1914)

Unlike Analytical Cubist works, paintings rendered in the Synthetic Cubist style were simplified, polychromatic, and inspired by collage art. Like the former phase of the movement, however, these paintings convey an interest in abstraction.

Guitar and Jug on a Table (1918) (Photo: Wiki Art, Public domain)

This part of the period officially lasted until 1914, though Picasso would continue to dabble in the style until the 1920s.

Neoclassicism (1917-1925)

Gradually shifting from the near-abstraction of Synthetic Cubism, Picasso adopted a Neoclassical style in 1917. This change occurred shortly after the artist's first visit to Italy, where he was inspired by the naturalism found in Italian Renaissance paintings.

Aiming to emulate these Renaissance artists, he returned to figurative painting—though, as evident in Woman Reading and The Pan Flute, they are not rendered in a style as realistically as his early works.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Surrealism (1925-1932)

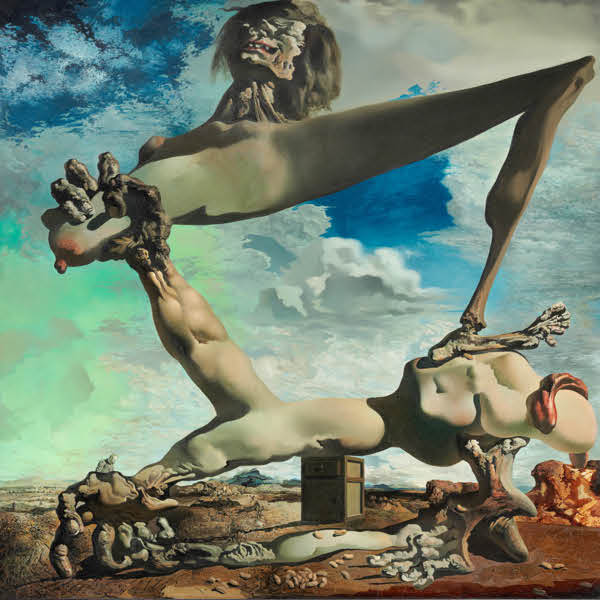

Following Neoclassicism, Picasso again moved away from naturalism. In 1925, he began working in a style deemed Surrealist, characterized by dreamy depictions of figures with disorganized facial features and twisted bodies. This “surreal” quality is emphasized by an unnatural palette of bright tones and clashing colors, as well as a skewed sense of perspective and a contrast between organic and geometric forms.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Though Picasso is not considered a Surrealist painter, his paintings from this period made major contributions to the movement.

Late Work

After his Surrealist period and until his death in 1973, Picasso continued to paint. However, unlike his previous work, the pieces produced during this time are not categorized into certain styles, as they each incorporate different elements of his past periods. This approach culminated in an eclectic collection of paintings that illustrate the influence of his changing style and remind viewers of his endless talent.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Picasso's most famous piece?

Picasso had many famous pieces, but one of his most notable is the monumental Guernica, painted in 1937.

Did Van Gogh know Picasso?

No, they didn't know each other.

Did Picasso paint the Mona Lisa?

No, Picasso didn't paint the Mona Lisa. Italian artist Leonardo Da Vinci painted it.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Simple Line Tattoos Inspired by Surreal Artists Like Picasso

Guggenheim Releases More Than 1,700 Masterful Works of Modern Art Online

Brightly Colored Tattoos Inspired by Picasso’s Cubism Paintings