John Everett Millais, “Ophelia,” ca. 1851 (Photo: Google Art Project Public Domain)

For centuries, painters have looked to Renaissance artists as masters of the craft. Vincent van Gogh called Michelangelo's figures “magnificent.” In his early work, Pablo Picasso emulated the style of Raphael. Surrealist Salvador Dalí described the Renaissance as the result of “divine genius.”

With such high praise, it's hard to believe that anyone could dislike the art of the Renaissance. However, in the 19th-century, a group of emerging artists in England formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a secret society dedicated to denouncing the movement—and starting their own.

Who were the Pre-Raphaelites?

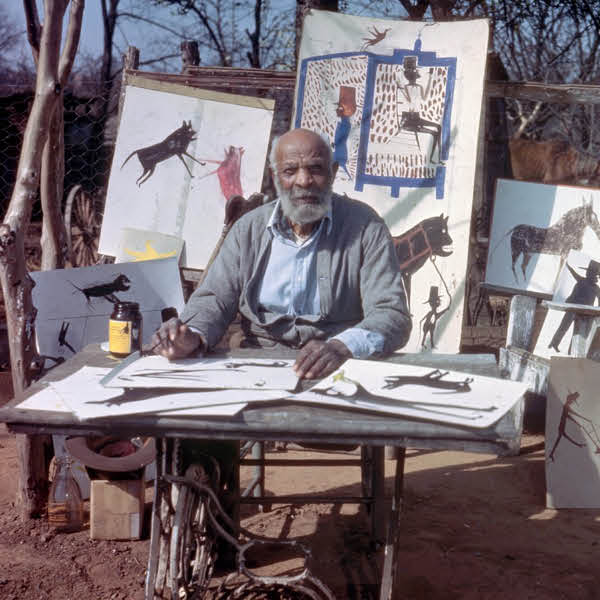

The Pre-Raphaelites were a group of painters and poets living and working in Victorian England. Established by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1848, the group was founded to counter ideals popularized during the High Renaissance. Specifically, Hunt, Millais, and Rossetti believed that art was in its golden age pre-Raphael—a painter often praised for his idealized approach to his subject matter—and sought to bring naturalism and realistic detail back to painting.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “La Ghirlandata,” 1873 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In order to achieve this goal, these three artists—as well as painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens, sculptor Thomas Woolner, and secretary William Michael Rossetti—banded together to create a secret brotherhood. Inspired by age-old art and supported by contemporary critic John Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelites sought to “go back to nature” and reinvigorate Europe's 19th-century art scene.

The Beginnings of the Brotherhood

For one year, the artists worked under the radar, foregoing traditional lessons at the Royal Academy of Art for secret meetings in their London homes. In 1849, however, they decided to reveal themselves to the public by exhibiting two paintings at the Royal Academy: Isabella by Millais and Rienzi by Hunt. In addition to their names, the artists marked the canvases with the initials “PRB”—though critics did not seem to pick up on this clue.

John Everett Millais, “Isabella,” 1849 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

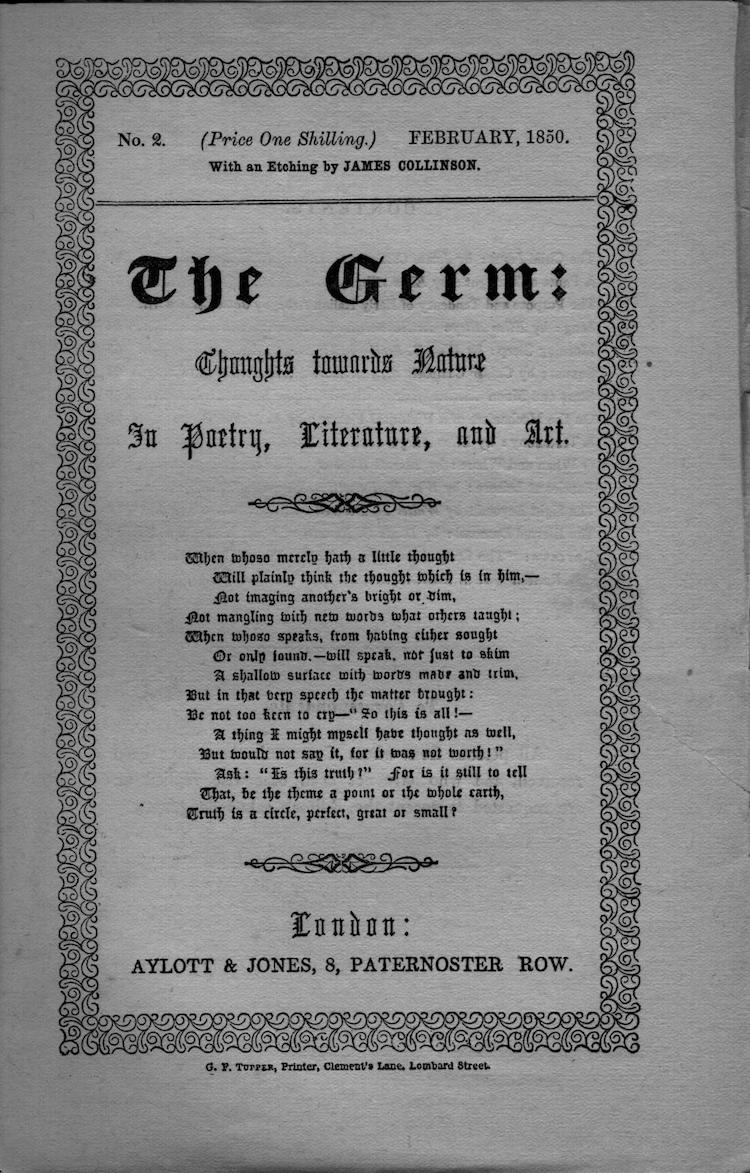

Thus, they made their more formal debut by way of print. In January 1850, they released the first issue of The Germ, a periodical that shared their work and views. In addition to illustrations, etchings, and poems by various group members, The Germ also published essays on art and literature by people associated with the movement.

After two poorly received issues, the Pre-Raphaelites decided to change the name of their magazine to Art and Poetry, being Thoughts towards Nature, conducted principally by Artists. This re-branding did not positively affect sales, however, and the publication was cancelled after two months.

Title page of “The Germ,” 1850 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

The PRB Disbands

Following an uneventful exhibition and failed magazine, two controversies plagued the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. First, Christ in the House of His Parents—a painting by Millais, one of the group's most prominent members—was deemed “ugly” and, therefore, blasphemous. Leading the crusade against Millais? None other than Charles Dickens, one of Victorian England's most important writers.

In a scathing review, Dickens called Millais' Christ “a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a nightgown, who appears to have received a poke playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a monster in the vilest cabaret in France or in the lowest gin-shop in England.”

John Everett Millais, “Christ in the House of His Parents,” 1850 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In addition to this negative press, the group also experienced some personal drama. After a group trip to Scotland, Millais ran away with Effie Gray, the wife of John Ruskin—their most outspoken supporter. Unsurprisingly, Ruskin was not kind to Millais in his subsequent reviews, and Millais eventually distanced himself from the group, which dissolved by 1853.

While these controversies undoubtedly led to the demise of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the group itself was not built on a stable foundation. Ultimately, its members were connected more by a desire to shake up the art world than they were by shared artistic goals. “Their aims were vague and contradictory, even paradoxical,” the British Library explains, “which was only to be expected from a youthful movement made up of strong-minded individuals who sought to modernize art by reviving the practices of the Middle Ages.”

Pre-Raphaelite Painting

Still, even with differing views and artistic approaches, the paintings produced by the Pre-Raphaelites did share some similar characteristics. These include a naturalistic and detailed approach to art, an interest in narrative subject matter, and, most famously, a preference for women with long, red hair. Each of these qualities is embodied by Millais' Ophelia, a painting inspired by Shakespeare's Hamlet.

John Everett Millais, “Ophelia,” (detail) ca. 1851 (Photo: Google Art Project Public Domain)

Millais completed the painting the year before the group disbanded. Even though it was created in the midst of controversy, the piece was met with much success, with critics calling it a “tour de force of detailed depiction” and “one of the most imaginative and powerful pictures in the exhibition.” Today, it remains an icon of the movement, and a prized gem of the Tate Britain, a London museum with an extensive Pre-Raphaelite collection.

The Group's Legacy

John William Waterhouse, “The Lady of Shalott,” 1888 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Though short-lived, the Pre-Raphaelite movement was an influential period in art history. They inspired numerous artists, including Arts & Crafts pioneer William Morris and acclaimed English painter John William Waterhouse; movements, like Symbolism; and even literature. In fact, it is widely speculated that J. R. R. Tolkien looked to the Pre-Raphaelite's mythological scenes while writing The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

While the Pre-Raphaelite movement may not have been appreciated or even accepted during its fleeting, four-year existence, its legacy is apparent today—and likely will be for years to come.

Related Articles:

19th Century Victorian Portraiture by Julia Margaret Cameron

The History of the Color Orange: From Tomb Paintings to Modern-Day Jumpsuits

Interview: Researcher Creates Free Archive of Over 3,000 19th-Century Shakespeare Illustrations