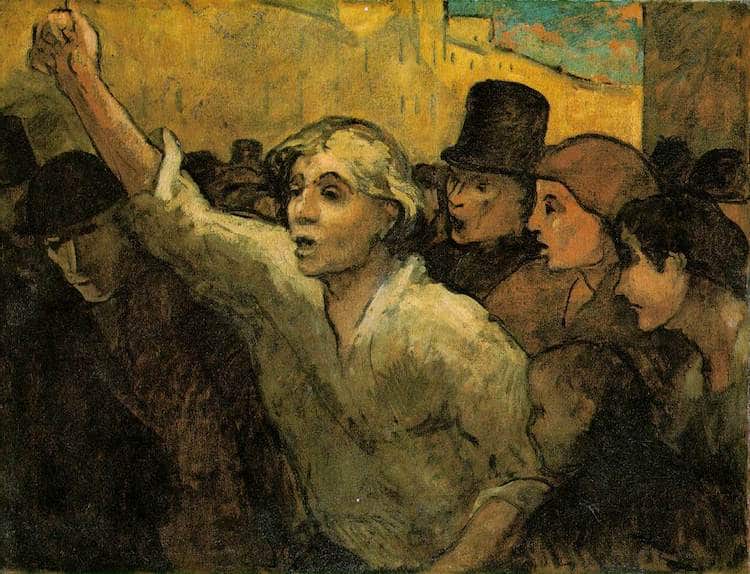

Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty Leading the People,” 1830 (Detail)

In 1830, French artist Eugène Delacroix described an ambitious new project in a letter to his brother. “I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her,” he wrote. “It has restored my good spirits.” This work-in-progress would become Liberty Leading the People, a large-scale painting portraying a subject favored by forward-thinking artists: revolution.

Spanning country, culture, and time, art inspired by revolution—an uprising intended to overthrow a government or social system—knows no bounds. Here, we explore a collection of works sparked by this politically-charged subject, with Delacroix's monumental masterpiece leading the way.

See how revolutions around the world have sparked art for centuries.

Liberty Leading the People by Eugène Delacroix

Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty Leading the People,” 1830 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Liberty Leading the People depicts Delacroix's allegorical interpretation of the July Revolution, a conflict that took place on the 27th, 28th, and 29th of July, 1830. Set on the streets of Paris (Notre-Dame Cathedral can be seen in the smoky distance), the painting features a woman leading revolutionaries to victory. Triumphantly holding the tricolor (the red, white, and blue flag of the revolutionaries and, later, of France) and sporting a Phrygian cap (a hat historically worn by freed slaves), this symbolic figure is believed to be an early version of Marianne, a personification of the French Republic.

Delacroix was living in Paris at the time, enabling him to experience the chaos firsthand. “Three days amid gunfire and bullets, as there was fighting all around,” he wrote in 1830. “A simple stroller like myself ran the same risk of stopping a bullet as the impromptu heroes who advanced on the enemy with pieces of iron fixed to broom handles.”

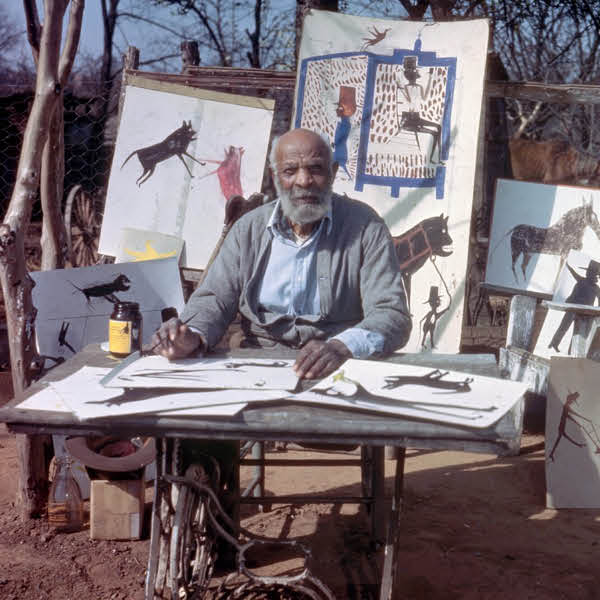

The Uprising by Honoré Daumier

Honoré Daumier, “The Uprising,” 1848 or later (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Honoré Daumier, a French artist known for his caricatures, documents the Revolution of 1848 in The Uprising, an empowering oil painting described by collector Duncan Phillips as a “symbol of all pent up human indignation.” While Delacroix—a Romantic painter known for his action-packed paintings—captured the epic drama of the French Revolution, Daumier approached it from a place of introspection. “The regard is directed inward,” French art historian Henri Focillon said. “The rioter is possessed by a dream to which he assembles the crowd.”

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze

Emanuel Leutze, “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” 1851 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Completed in 1851, this grand painting depicts a pivotal moment in American history: George Washington's successful surprise attack on the Hessians, German troops fighting for the British, in Trenton, New Jersey, on December 25, 1776. In Leutze's piece, Washington is shown heroically leading an army of 2,400 men across the icy river, capturing the heightened drama of this historic moment. “Without the determination, resiliency, and leadership exhibited by Washington while crossing the Delaware River the victory at Trenton would not have been possible,” Mount Vernon, Washington's estate-turned-National Historic Landmark, explains.

The Third of May 1808 (Execution of the Defenders of Madrid) by Francisco Goya

Francisco Goya, “The Third of May,” 1808 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Regarded as both an Old Master and as a forefather of modern art, Goya's entire body of work is widely considered “revolutionary.” According to renowned British art historian and museum director Kenneth Clark, however, The Third of May 1808 takes this descriptor a step further, as it “can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention.”

New Planet by Konstantin Yuon

Konstantin Yuon, “New Planet,” 1921 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

The Arsenal by Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera, “The Arsenal,” 1928 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Fair Use])

Beginning in 1911, the Mexican Revolution was a political crisis ignited by the working class' growing disdain for the president's elitist policies. While the Revolution officially ended in 1917 with the Constitution of Mexico, fighting lasted into the 1920s, culminating in over one million lost lives. Completed at the movement's tail end, The Arsenal features Kahlo front and center as she distributes weapons to workers-turned-soldiers. Above the figures is a banner inscribed with lyrics from “Así será la Revolución Proletaria” (“So Will Be The Proletarian Revolution,”) a corrido, or Mexican ballad, by Rivera.

“Son las voces del obrero rudo lo que puede darles mi laúd” (“It is the voices of the rough worker that my lute can give them”), the banner reads.

Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads by Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei, “Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads,” 2010 (Photo: Stock Photos from Pabkov/Shutterstock)

Today, contemporary artists continue to find inspiration in revolution. In Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei attempts to remedy the disastrous results of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a period of death and destruction.

The Cultural Revolution erupted in 1966, when Mao Zedong sought to strengthen his control over the Communist party. On top of a collapsed economy and a death toll likely in the millions, this revolution culminated in the destruction of China's material culture, igniting a new appreciation for its surviving artifacts.

For Ai Weiwei, this included the famous Zodiac Fountain at the Yuanming Yuan palace in Beijing, a “popular site for artists like Ai to paint and sketch.” Adorned with a dozen animal heads, this 18th-century water fixture served as the inspiration for Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, a sculptural installation that—in addition to reacting against the core of the Cultural Revolution—is revolutionary itself.

“My work is always a readymade,” he said. “It could be cultural, political, or social, and also it could be art—to make people re-look at what we have done, its original position, to create new possibilities. I always want people to be confused, to be shocked or realize something later. But at first it has to be appealing to people.”

Related Articles:

‘The Death of Marat’: A Powerful Painting of One of the French Revolution’s Most Famous Murders

How the Groundbreaking Realism Movement Revolutionized Art History

How David’s ‘Death of Socrates’ Perfectly Captures the Spirit of Neoclassical Painting