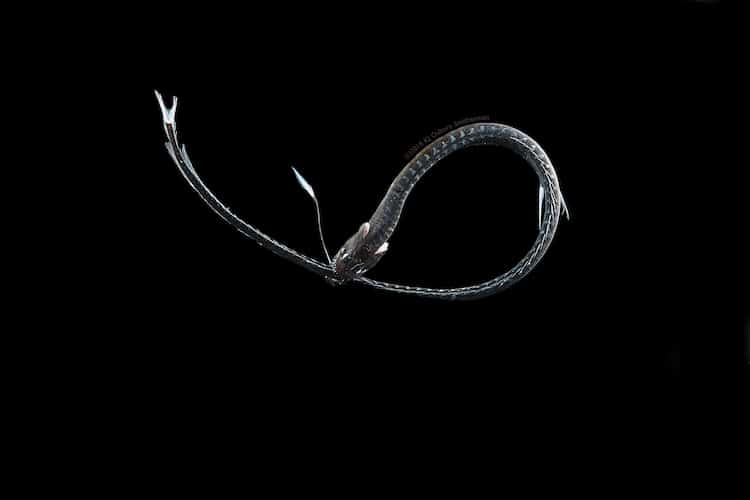

Pacific blackdragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus)

We all know that some strange creatures can live in the deep sea, but even researchers were surprised by the adaptation they found in some fish off the coast of California. In the depths of the ocean, far beyond where sunlight can penetrate, scientists have found several species of “Vantablack” fish. These fish actually absorb more than 99.5% of the light that hits them, making them nearly undetectable in the water.

A team of scientists, led by Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History research zoologist Karen Osborn and Duke University biologist Sönke Johnsen, found 16 fish species that showed this capability and published their research in Current Biology. It's an unusual find and one that the researchers weren't expecting.

In fact, they only realized these ultra-black properties when Osborn went to photograph one of the fish specimens they'd pulled to the surface. After setting up her strobe and taking a few shots, she noticed that one particular fish turned into a “black hole” as she tried to photograph it.

“I was trying to take pictures of it, and I was just getting these silhouettes,” Osborn recalled. “They were terrible. I had tried to take pictures of deep-sea fish before and got nothing but these really horrible pictures, where you can't see any detail. How is it that I can shine two strobe lights at them and all that light just disappears?”

Pacific blackdragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus)

That's when Osborn and her colleagues realized that they were looking at fish that had learned to camouflage themselves with their “Vantablack” skin. Deep underwater, where the sun doesn't penetrate, bioluminescence given off by different animals provides light. It's how animals not only mate, but how predators find their prey. Making oneself invisible in these situations is the difference between life and death. “If you want to blend in with the infinite blackness of your surroundings, sucking up every photon that hits you is a great way to go,” says Osborn.

The ultra-black quality of the fish is due to melanin. This pigment, which also colors the skin of humans, is not only abundant in the fishes' skin, but throughout their entire body. As an initial barrier, densely packed pigment cells form a layer along the surface of the fish and absorb a great deal of light. Anything they don't immediately absorb then gets pushed to the other pigment cells deeper down, which take care of the rest. “Effectively what they’ve done is make a super-efficient, super-thin light trap,” Osborn says. “Light doesn’t bounce back; light doesn’t go through. It just goes into this layer, and it’s gone.”

While scientists have found birds with ultra-black feathers, the absorption system that these fish species are using is quite different. With birds and butterflies, the effect is a combination of melanin and light-capturing structures. This differs greatly from the fish, which are only using melanin.

Currently, researchers are thinking about how these fish could give them insight into how designers could more efficiently design ultra-black materials. Most manufacturers use the same principals found in birds and butterflies, but this discovery could open up a world of new possibilities.

Researchers have discovered 16 species of “Vantablack” fish.

Anoplogaster cornuta

Ultra-black ridgehead (Poromitra crassiceps)

These deep-sea fish have ultra-black skin that absorbs over 99.95% of light, making them invisible to predators.

Pacific blackdragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus)

Pacific blackdragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus)

All images via Karen Osborn/Smithsonian. My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Smithsonian.

Related Articles:

You Can Literally See Through the Head of This Fascinating Fish

MIT Engineers Discover World’s Blackest Black, Taking Title from Vantablack

200-Year-Old Giant Chinese Salamander Discovered in a Cave by Local Fishermen

This Website Lets You to Scroll to the Bottom of the Ocean and Discover Deep Sea Animal Life