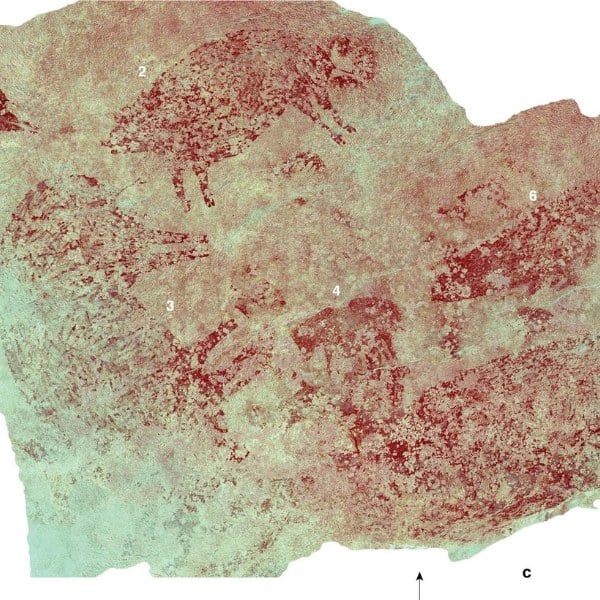

A student's writing board from the Middle Kingdom period, circa 1981–1802 BCE. The red marks are those of a teacher correcting their student's spelling. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Have you ever received test papers back from your teacher all decorated in red ink? Don't worry, you're not the only one. This standard form of correcting students' work is an ancient educational tradition—as evidenced by an ancient Egyptian writing board in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Dating to between 1981 and 1802 BCE, during the Middle Kingdom period, the gessoed board was a useful tool for apprentice scribes to practice their penmanship as they copied texts for their teachers to inspect.

Ancient Egyptian bureaucracy and industry required extensive record keeping and correspondence. To meet this need, promising young men trained as scribes from an early age. These apprentices learned from a master scribe, who instructed them in the technical skills of writing as well as the proper forms of documents, such as government letters, wills, and tax forms. The formal script used by the ancient Egyptians in their tombs and carved monuments were hieroglyphics—a rich script with about 1,000 distinct characters representing sounds and concepts. However, this script was laborious to use and hardly ideal for the massive amounts of paperwork required in Egyptian life.

A solution to the scribe's problem developed by about 3,000 BCE. A cursive version of hieroglyphics known as hieratic became the dominant script used in administrative and religious documents. The student's board above is an example of this script. As described by the Egyptologist William C. Hayes in his book The Scepter of Egypt, this exercise was written by a student named Iny-su, son of Sekhsekh. He writes (jokingly it seems) to his brother Peh-ny-su, treating him like a wealthy authority figure. The letter is practice for creating such formal and deferential correspondence later—a skill useful for a scribe in industry or government. Apprentice scribes like Iny-su would have been required to practice writing and memorize these useful form documents and letters.

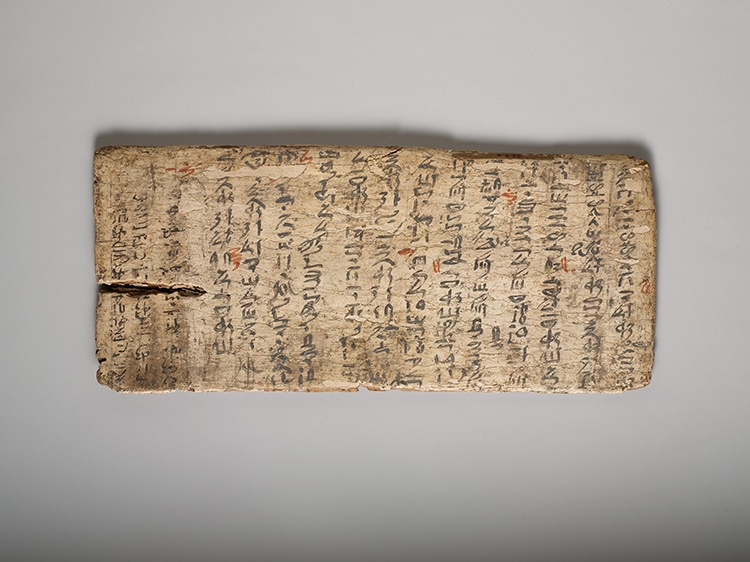

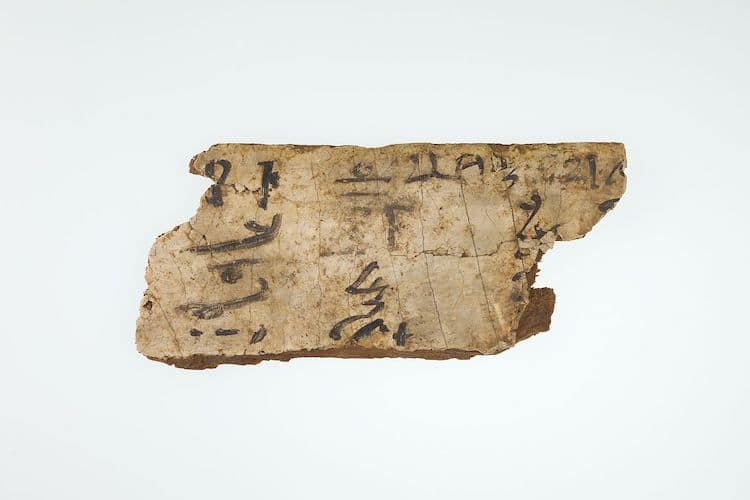

Fragments from a Scribe's Writing Board, ca. 2130–1981 BCE. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Modern knowledge of Egyptian scribes and their writings comes largely from artifacts found in tombs and other ancient sites. Scale models found in tombs depict scribes sitting on the ground, often cross-legged. They hold tablets much like the one used by Iny-su. These writing boards were crafted from wood and could be framed in precious materials such as ebony. The surface of the board would be written on, then painted over in white gesso (much like artists do with their canvases). In this way, students could practice their penmanship and boards could be resumed. Apprentice scribes also often practiced on ostraca—broken pieces of pottery which were recycled for writing. More practiced scribes could also use stone, papyrus, leather, or clay tablets.

The master scribe's corrections appear in red ink—just one of the many colors available to Egyptian scribes. Archeologists have found rich and colorful pigments preserved in palettes left behind by ancient artisans. A standard writing palette might hold two colors of ink as well as reed brushes. The ink was mixed from pigment and a light gum. Before writing, the scribe might cut his reeds into a sharp point using a knife. For a more brush-like tip, he could also chew the end of the reed. Mistakes could be painted over or scraped away depending on the writing surface. Young Iny-su was just getting started with his career when he completed this writing assignment 4,000 years ago. Like other Egyptian scribes, he was a vital part of the kingdom's everyday business.

A 4,000-year-old Ancient Egyptian writing board shows the writing assignment of an apprentice scribe being corrected by his teacher in red ink.

Scribes from Meketre's Model Granary, from the Middle Kingdom circa 1981 to 1975 BCE. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Apprentice scribes learned their trade from master scribes, who taught penmanship and the proper forms of letters and documents used in the Egyptian bureaucracy.

Writing board of an apprentice scribe, showing formal hieroglyphics which are oddly spaced and inexpertly shaped. From the First Intermediate Period, circa 2030 BCE. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

The writing boards were repeatedly made into “clean slates” by painting over a student's work with white gesso.

Palette inscribed for Smendes, High Priest of Amun, circa 1045–992 BCE. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Scribes wrote on boards, pottery, and papyrus using ink, reed brushes, and palettes.

Writing board which is missing most of the gesso which once covered it. From the Middle Kingdom, circa 2030–1981 BCE. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Whether in formal hieroglyphics or the cursive hieratic script, scribes left behind a wealth of writings and were important workers in ancient Egypt.

Scribe's Knife from the burial of Amenemhat, New Kingdom, circa 1504–1447 BCE. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

h/t: [Open Culture]

Related Articles:

This Virtual Tour Takes You Inside an Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh’s Tomb

This “Normal” Drinking Glass Is Actually an Ancient Greek Party Prank

What Is Ancient Assyrian Art? Discover the Visual Culture of This Powerful Empire

Archaeologists Unearth an Incredibly Well-Preserved Ancient Food Stall in Pompeii