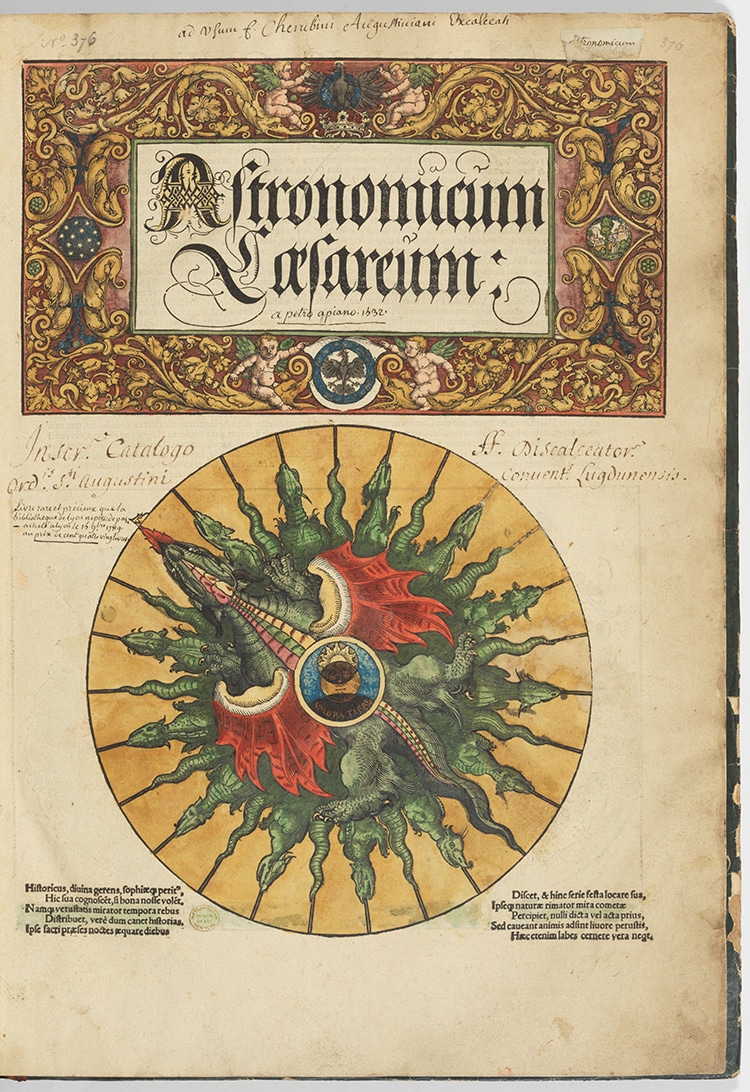

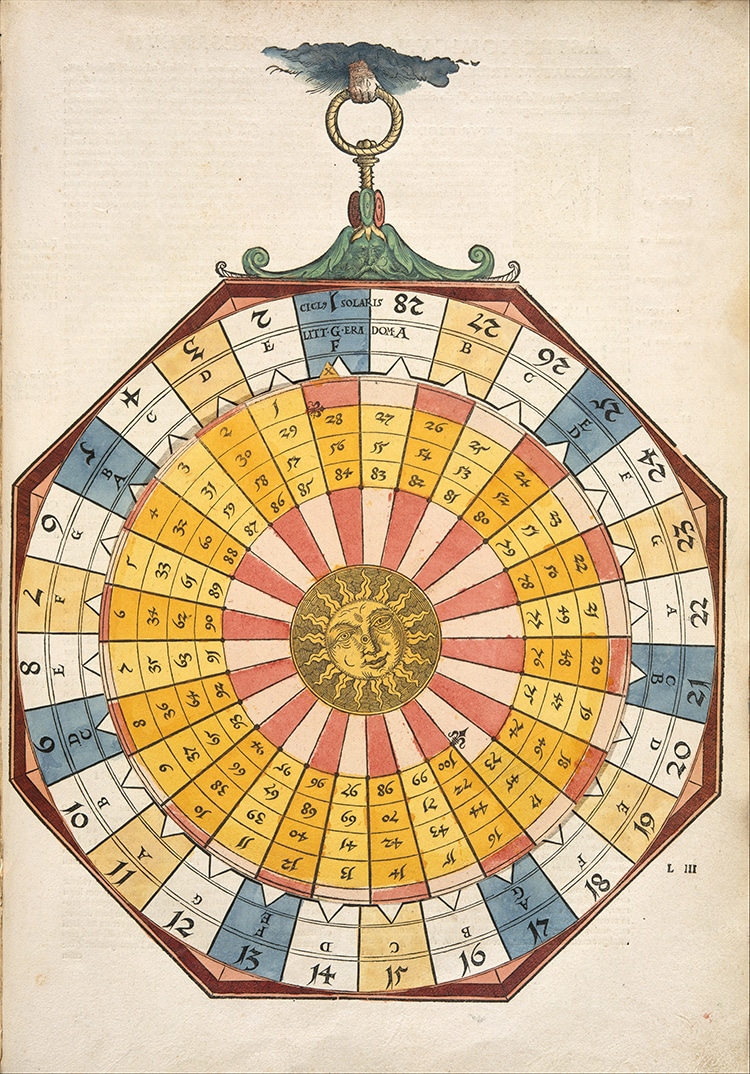

“Astronomicum Caesareum,” by Petrus Apianus, illustrated by Michael Ostendorfer, May 1540. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

It's 1540 and you'd like to cast a horoscope. If you are the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, you might turn to the Astronomicum Caesareum, or the Emperor's Astronomy. This richly illuminated manuscript is a stunning example of early printing and astronomical inquiry. The rich scientific tome was authored by court astronomer Petrus Apianus and published in May 1540. Today, it still stands out as one of the most stunningly artistic scientific works published in the Renaissance.

The volume pictured here is held at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which calls it the “most sumptuous of all Renaissance instructive manuals.” Like many books in the early years of the printing press, the type was printed and the illustrations were made with cut woodblocks. These illustrations were then precisely colored by hand. Astronomicum Caesareum was particularly well-crafted.

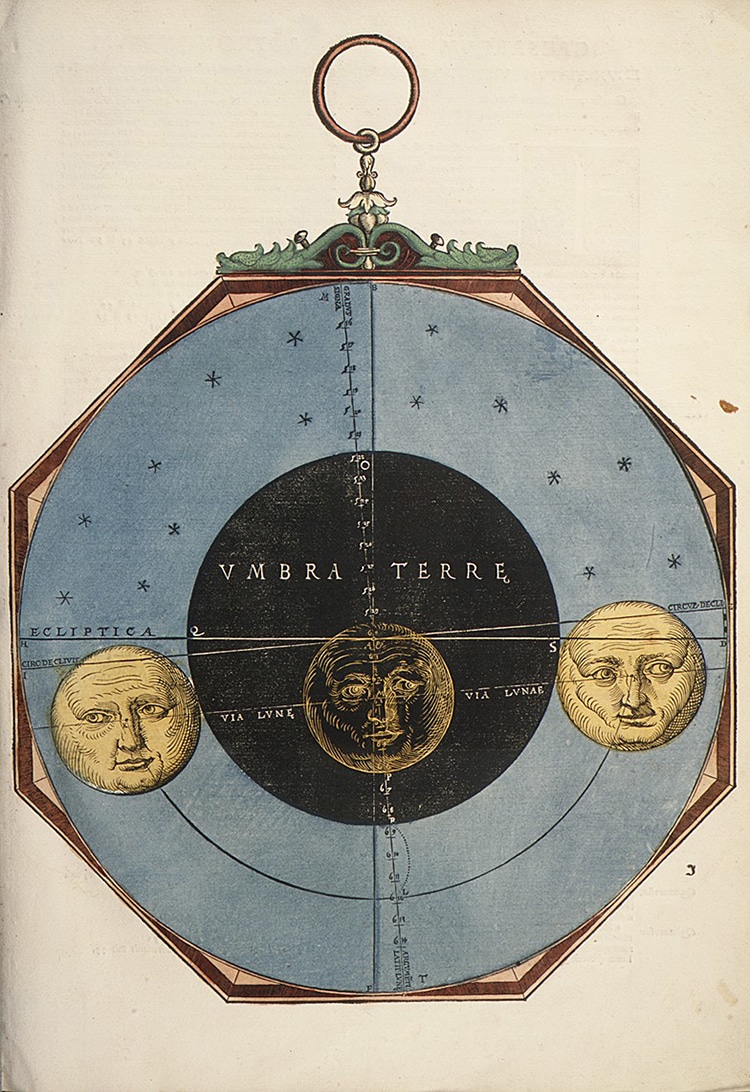

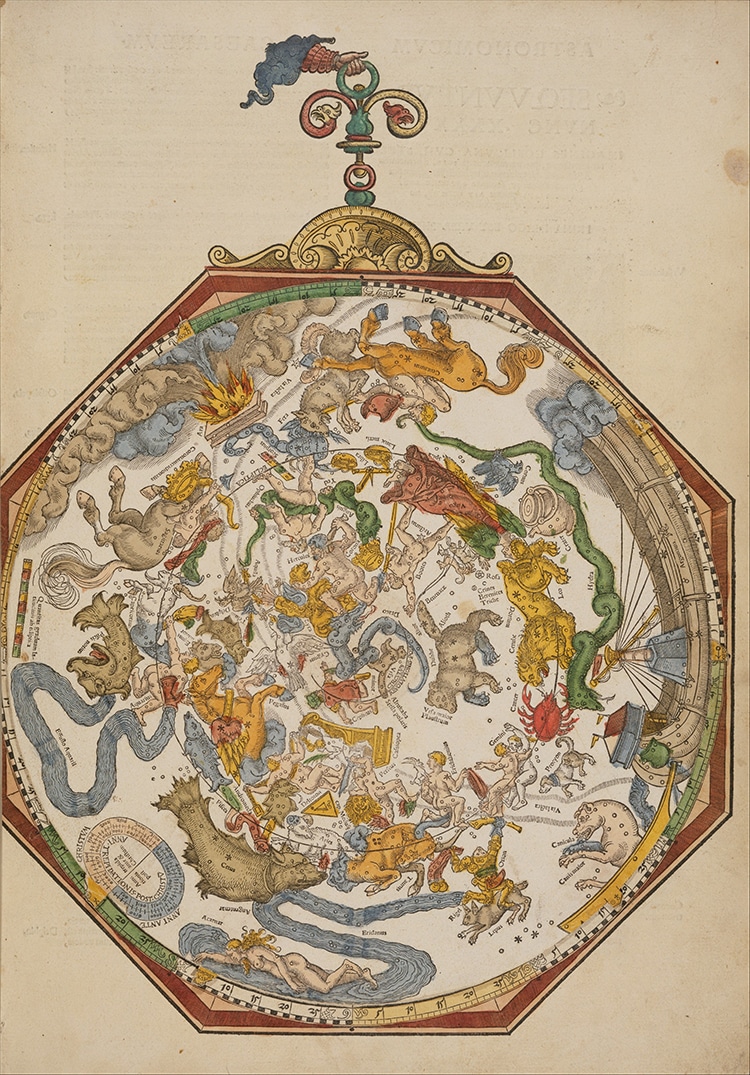

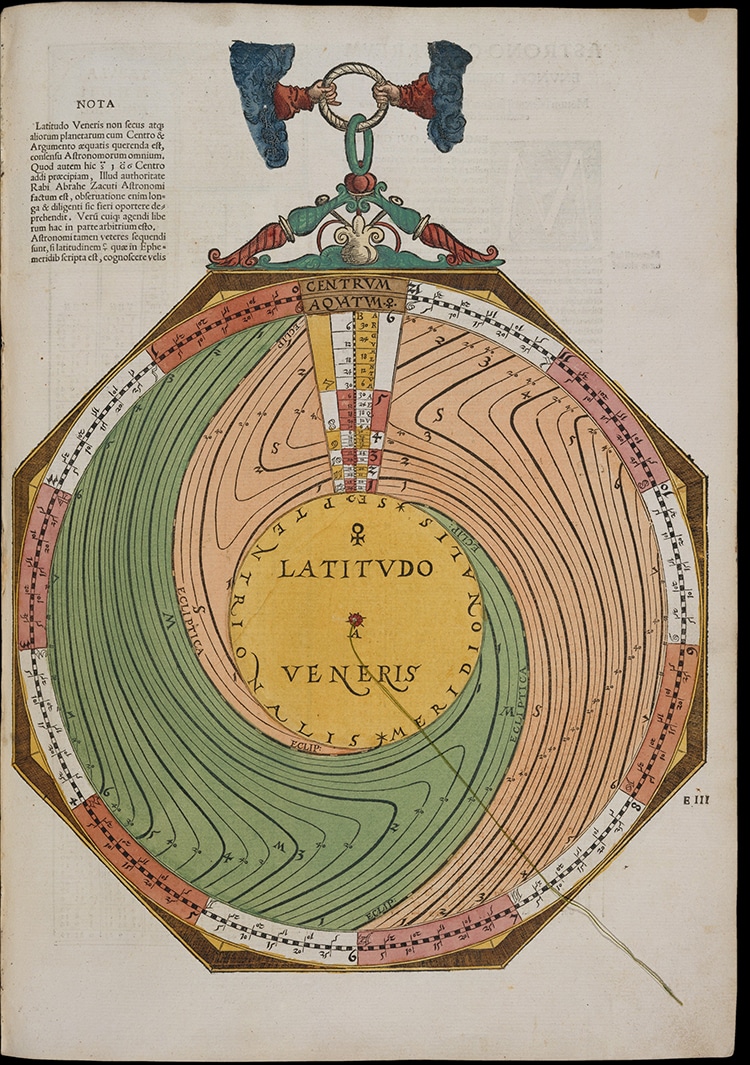

The volume contains 21 moving paper parts. Circular paper “spinners” called volvelles function as “computers” as they are arrayed with astrological information. The user could spin the layers to align the planets and calculate horoscopes or eclipses. A thread attached to the center of each volvelle used to feature small, luxurious seed pearls. This mimicked the function of the astrolabe—typically a hand-held, metal astronomical instrument. Apianus created horoscopes using these methods for Emperor Charles V and his brother Ferdinand I. This was a tribute to his noble patron, one which earned him extra privileges from the emperor.

In the Renaissance, astronomers and astrologers were largely one and the same. An emperor valued the predictive and research endeavors of his astronomers. So, how accurate were the astrological insights of Astronomicum Caesareum? The text is based on a geocentric model of the world—the dominant view before the publication of the works of Copernicus. However, despite this inaccuracy, Apianus accurately identified the paths of five comets including Halley’s Comet. He also was able to predict a future eclipse while describing some historical ones.

To learn more about the making of books such as Astronomicum Caesareum, check out this video of woodcut printing from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

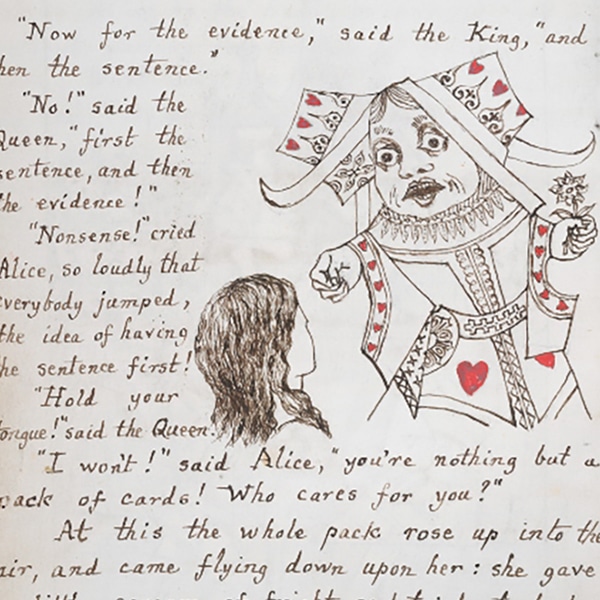

The Astronomicum Caesareum is a richly illustrated Renaissance scientific manuscript.

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain

The book features many moving paper models that function like astrolabes.

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain

The author, Petrus Apianus, used these moving diagrams to cast horoscopes and track the heavens.

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain

Only about 40 copies of this early printed work survive.

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain

Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain

h/t: [Open Culture]

Related Articles:

What Is a Reliquary? Here’s a Short Introduction To the Bejeweled Medieval Vessels

Where to View Leonardo da Vinci’s Notebooks Online for Free

Who Was Albrecht Dürer? Learn About the Pioneering Northern Renaissance Printmaker

Rarely-Seen Illustrations of Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’ Are Now Free for All To View Online