Berthe Morisot, “Self-Portrait,” 1885 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

As the catalyst of modern art, it's no surprise that Impressionism remains one of art history's most innovative movements. Impressionist artists are known for their avant-garde approach to brushwork and interest in capturing fleeting impressions of the world around them. In addition to these technical developments, Impressionism was groundbreaking for another reason: its inclusion of women.

Though the movement was still male-dominated, a few women were able to make a name for themselves among Paris' premier Impressionists, with Berthe Morisot being the first.

Berthe Morisot (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Artistic Background

Full Name | Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot |

Born | January 14, 1841 (Bourges, France) |

Died | March 2, 1895 (Paris, France) |

Notable Artwork | Lady at Her Toilette |

Movement | Impressionism |

In 1841, Berthe Morisot was born in Bruges, France. At the age of 11, she and her family moved to Paris, where she—like most other wealthy young girls—received private art lessons from Joseph Guichard, a French painter. On top of teaching her technical skills, Guichard helped Morisot break in to the Parisian art scene by introducing her to established artists, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Édouard Manet, whose brother she would eventually marry.

Morisot also met other artists while working as a copyist at the Louvre, and was part of Paris' up-and-coming circle of artists by the mid-1860s.

Édouard Manet invited Morisot to model for his painting, “The Balcony,” in 1868. She is shown sitting. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

While Morisot would eventually be known for her work in oil paint, she dabbled in drawing and sculpting early in her career. Unfortunately, not many of these pieces exist today. Working under the belief that she was “incapable of doing anything properly,” Morisot destroyed a substantial number of works of art created in the 1860s. This attitude shifted in 1870, however, when Morisot found her niche in en plein air (“open air”) painting, a technique that would come to define Impressionism.

Berthe Morisot, “The Harbor at Lorient,” 1870 (Photo: Wiki Art Public Domain)

Joining the Impressionists

From 1864 until 1873, Morisot saw success in Paris' salons, annual exhibitions that adhered to the traditional tastes of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. These shows tended to favor conventional subject matter—including historical, mythological, and allegorical scenes—rendered in a realistic style, making them the antithesis of Impressionist ideals.

Toward the end of her salon stint, Morisot was becoming increasingly experimental in her work, often mixing watercolors, oil paint, and pastels on a single canvas. When paired with her growing interest in painting outside of the confines of a traditional studio, this shift in style prompted Morisot to forego the salon and instead join the Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs.

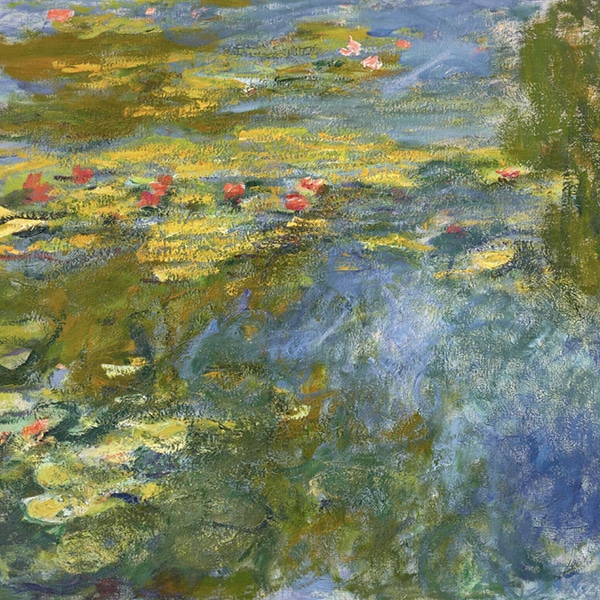

Eventually known as the Impressionists, this group of artists included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro. In 1874, they held their first independent exhibition. Morisot showed The Cradle, an oil painting that would eventually become her most well-known work of art.

Berthe Morisot, “The Cradle,” 1872 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

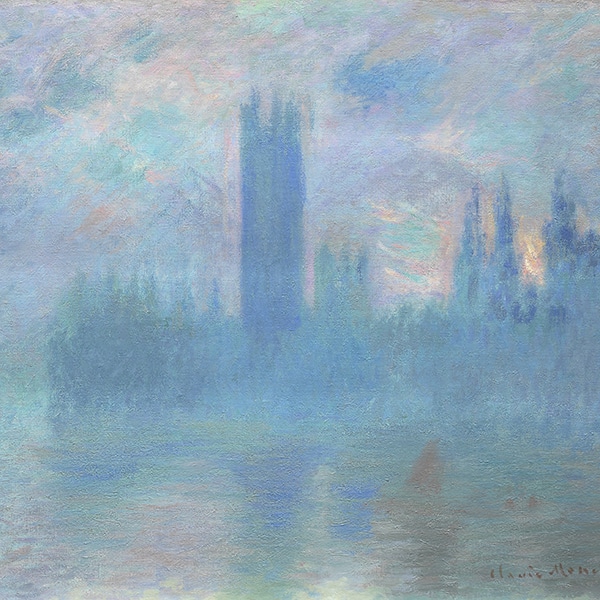

While the exhibition was met with mixed reviews (one critic infamously compared Claude Monet's iconic Impression, Sunrise to “wallpaper in its most embryonic state”), Morisot's piece was praised for its “feminine grace.”

“Feminine” Style

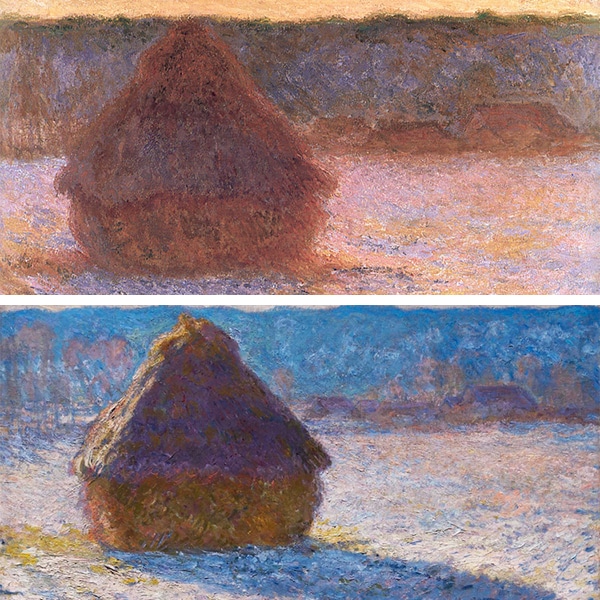

For her entire career, Morisot's work would continue to be described as “feminine.” This characterization can be attributed to two predominant characteristics: a soft color palette and a delicate touch.

Color

No matter the medium, Morisot preferred working in pastel tones and incorporating an abundance of white into her compositions. With this palette, her works adopted an ethereal feel: in her portraits, human skin takes on a porcelain-like aesthetic; in her seascapes, the ocean looks like glass; and, in her landscapes (e.g. Hanging the Laundry out to Dry) the sky becomes cotton candy.

Berthe Morisot, “Hanging the Laundry out to Dry,” 1875 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Morisot's exquisite treatment of color was praised by her fellow artists and contemporary critics alike. “Here is a delicate colorist,” French art critic Philippe Burty remarked in 1877, “who succeeds in making everything cohere into an overall harmony of shades of white.”

“Freedom of Handling”

Much like her use of color, Morisot's approach to brushwork and her handling of pastels became intrinsic to her art—and one of her most celebrated skills.

“Her watercolors, her pastels, her paintings all show. . . a light touch and unpretentious allure that we can only admire,” critic Georges Rivière said in 1877. “Mademoiselle Morisot has an extraordinary sensitive eye [and] succeeds in capturing fleeting notes on her canvases, with a delicacy, spirit, and skill that ensure her a prominent place at the center of the Impressionists' group.”

Berthe Morisot, “The Cherry Picker,” 1891 (Photo: Wiki Art Public Domain)

Poetically described by the Musée Marmottan as a “freedom of handling,” this technical skill was a perfect match for her preferred subject matter: breezy landscapes in Normandy, warm South of France seascapes, and children playing in blossoming gardens.

Late Career and Legacy

Morisot continued to hone her “feminine” style as she navigated her career. With the emergence of photography, she began experimenting with cropped compositions in the 1880s. And, inspired by the graphic aesthetic of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, she played with line in the 1890s. Even with these new developments, however, she retained the pastel palette and graceful “touch” characteristic of her Impressionist phase.

Berthe Morisot, “Before the Mirror,” 1890 (Photo: Wiki Art Public Domain)

Today, her work is not as well-known as that of her male contemporaries, but many museums still regard her as one of the movement's key innovators—and, along with fellow Impressionist Mary Cassatt, she is recognized as one of art history's most important female figures.

Related Articles:

The History of the Color Blue: From Ancient Egypt to the Latest Scientific Discoveries

Empowering Art Book Highlights Female Artists Overlooked by Museums

Online Database Features Overlooked Female Artists from 15th-19th Centuries