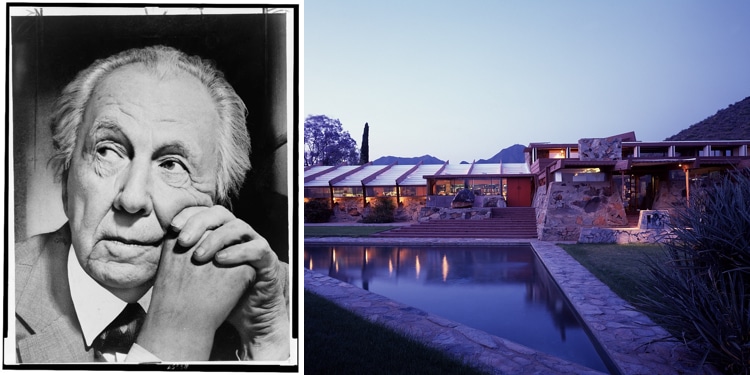

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1954 (Photo: Library of Congress) / Taliesin West, 1937. Scottsdale, AZ (Photo: Library of Congress). This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

With a career spanning over 70 years, American architect Frank Lloyd Wright changed the course of American architecture. Born in Wisconsin in 1867, Wright spent his formative years in the Midwest, and it was in Chicago, where he was hired as a draftsman at an architectural firm, that his career would take off after opening his own studio in 1893.

During his career, he designed more than 1,000 structures, with about 650 actually being constructed. As an architect, interior designer, writer, and educator, he was incredibly prolific. In fact, in 1991, the American Institute of Architects named him “the greatest American architect of all time.” Many of his buildings have been named UNESCO World Heritage sites and he is credited with creating the first American style of architecture. Just what is it about Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture that has left such a legacy?

Wright felt strongly that architecture was the great record of each civilization and that architects were the poets of their time, with a duty to capture their moment in history. He was able to break barriers as an innovator, moving from closed, restrictive Victorian architecture into a new American genre that favored clean lines and open spaces. Inside and out, his buildings play off nature, and have left a legacy that still pervades modern architecture and decorative arts.

Full Name | Frank Lloyd Wright |

Born | June 8, 1867 (Richland Center, Wisconsin) |

Died | April 9, 1959 (Phoenix, Arizona) |

Notable Work | Fallingwater, Guggenheim Museum |

Movement | Prairie School, Modernist |

Robie House, 1909. Chicago, IL (Photo: Stock Photos from Marek Lipka-Kadaj/Shutterstock)

Styles of Architecture

We've all heard of Frank Lloyd Wright, but what is it about his architecture that has made such a lasting impression? Of course, with such a long career, his style evolved, allowing us to categorize his work into distinct categories that evolve into one another.

Unity Temple, 1905-1908. Oak Park, IL (Photo: Stock Photos from Nagel Photography/Shutterstock)

Prairie School

Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement, which is exemplified by his Prairie homes built between 1900 and 1914. Born in the Midwest, the Prairie School attempted to develop a distinctly American architectural style that was not influenced at all by European styles. Low-pitched roofs, overhanging eaves, and an open floor plan are hallmarks of the style. The wide, flat expanse of the buildings was meant to mimic the prairie landscape found in the surrounding area. Natural materials like wood and stone also help integrate the buildings with the environment, something that would become increasingly important to Wright’s work.

He also used coordinated design elements based on nature throughout the homes, whether in stained glass or custom-designed furniture. The Robie House in Chicago is a prime example of his residential work during this period, while the Unity Temple in Oak Park is a public building done in the Prairie style. Both of these buildings remain some of Frank Lloyd Wright's most famous pieces of architecture.

Ennis House, 1924. Los Feliz, CA. (Photo: Mike Dilon via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Mayan Revival

Wright then began transitioning into a style influenced by Mayan and Egyptian architecture. The linear style made use of precast concrete blocks and was called the textile style. This work unfolded over the 1920s, primarily in a series of houses in California. As always, landscape was a big consideration, with large expanses of glass used to blur the boundaries between indoors and outdoors. The Ennis House in Los Feliz, which is sometimes called Mayan Revival architecture, exemplifies Wright’s work in this style.

Interior, Rosenbaum House, 1940. Florence, AL. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Usonian

Moving into the 1930s, Wright built a series of 60 homes known as Usonian houses. The architect used the word Usonian to describe his vision of the American landscape, one that would be free of prior architectural notions. These homes were typically one story, without attics, basements, or much storage. Their flat roofs and cantilevered overhangs allowed for passive heating and cooling, and they possess a strong visual connection between indoor and outdoor.

It’s with his Usonian homes that Wright coined the word carport, used to describe the overhang that sheltered a parking spot. Wright’s concepts for Usonian homes are considered to be the roots of ranch-style houses that would gain popularity in the United States in the 1950s. The Rosenbaum House in Florence, Alabama, is considered “the purest example of the Usonian” by Frank Lloyd Wright scholar John Sargeant.

Frank Lloyd Wright, written by former apprentice Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, gives a comprehensive look at all the architect's work.

Organic Architecture

Fallingwater, 1936-1939. Mill Run, PA. (Photo: Carole B. Highsmith via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Wright began using the term organic architecture as early as 1908 to describe his architectural philosophy. It’s based on the harmony between human habitats and the natural world, with the design crafted to integrate the manmade architecture into the landscape. Unsurprisingly, much of this philosophy is influenced by Japanese architecture, which Wright would increasingly look to for inspiration throughout his career.

Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania, is perhaps Wright’s most famous example of organic architecture. The idea is for the architecture to blend so completely into the landscape that they become one and the same. “A building should appear to grow easily from its site and be shaped to harmonize with its surroundings if Nature is manifest there.”

This is also achieved through repeating patterns based on nature throughout the building, as well as the use of natural materials. With Fallingwater, Wright choice to place the home directly over the waterfall and creek helps create the close relationship with nature he desired. “No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.”

Want to spend the night in a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright? Cooke House, located in Virginia Beach, is available for rent on Airbnb.

Interior Design and Decorative Arts

Interior, Robie House. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Wright paid close attention to all aspects of the interior and exterior design of his buildings. In fact, he once wrote, “to thus make of a dwelling place a complete work of art… this is the modern American opportunity.” Unsurprisingly, he took care to design much of the furniture and decorative arts that went inside his homes and public buildings.

These decorative motifs, which took inspiration from sources as varied as Japanese screens and the Vienna Secession have left a lasting legacy. For instance, he was an early adopter of recessed lighting, often placing rice paper or decorative wood grilles in front of fixtures to filter light.

Prairie-style glass from Frank Lloyd Wright's house in Oak Park. (Photo: The Chicago Files)

He is perhaps best known for his work in leaded stained glass. From 1885 and 1923, when he stopped using the technique, Wright designed 163 buildings that included leaded glass of his own design. He thought of them as “light screens,” and their motifs show the distinct influence of Japanese prints that the architect would have seen when he first visited Japan in 1905. To this day, it’s possible to purchase furniture, prints, decorative items, and even coloring books using his intricate patterns.

Read more about Frank Lloyd Wright's interiors and decorative designs in Margo Stipe's Frank Lloyd Wright: The Rooms: Interiors and Decorative Arts.

The Guggenheim

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, completed 1959. New York City, NY. (Photo: Stock Photos from Tinnaporn Sathapornnanont/Shutterstock)

After WWII, having turned 80, Wright occupied himself with one of his most significant masterpieces, the Guggenheim in New York. He worked for 16 years, from 1943 to 1959, on the building. Using principles of organic architecture, the design is based on the spiral of a seashell.

Unfortunately, the building would open only 6 months after his death, with several of his final wishes ignored. For instance, the interior was meant to be painted off-white, and visitors were supposed to view the artwork by descending the central ramp, not traveling upwards as the museum now functions.

In fact, the architecture was initially faced with criticism. Wright wanted to make a museum whose physical space was just as impressive as the collection it housed—something now commonplace but at the time controversial. At the time, it was assailed by critics who dubbed it “washing machine,” an “imitation beehive,” and a “giant toilet bowl.” Over time, Wright’s most significant commission in New York was seen as a pivotal moment in museum architecture, liberating it from traditional archetypes and setting forth the age of modern museums.

Want to know more about Frank Lloyd Wright's life? Ken Burns' documentary may be what you are looking for.

Legacy

Photo: Daniel Daniel Hooker (CC BY-NC 2.0)

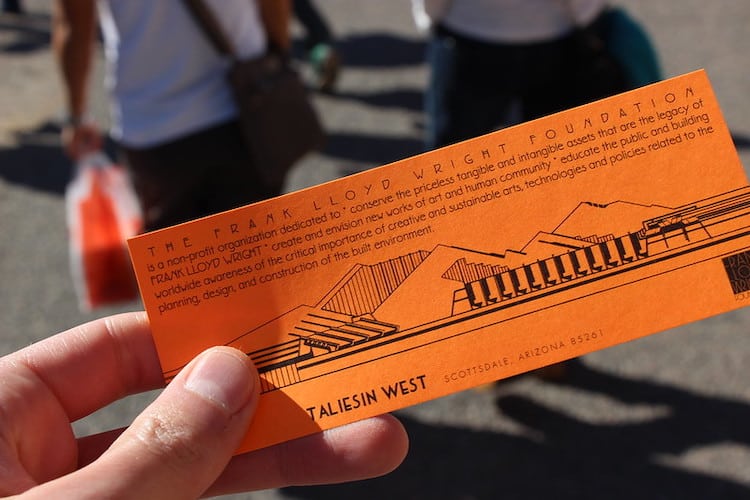

Today, Frank Lloyd Wright's legacy lives on, in large part due to the work of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Created by the architect in 1940, the organization preserves Wright's iconic homes and studio spaces, Taliesin and Taliesin West. They carry on the architect's mission of better living through a connection between nature and architecture by conducting educational programming and virtual events.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Conservancy was created in 1989 to “facilitate the preservation and stewardship of the remaining built works designed by Frank Lloyd Wright through advocacy, education, and technical services.” The organization works tirelessly to ensure that all of Wright's buildings are preserved and kept as the works of are they are.

In the professional world, Frank Lloyd Wright's legacy can be seen in increased attention to marrying architecture and nature. While he was a front-runner in blending his buildings into the natural landscape, his organic architecture philosophy has become a rallying try for many contemporary architects. And his ability to design anything, from a building facade to a piece of furniture, is an example that more and more designers are taking.

Wright's legacy as America's leading architect was cemented further in 2019 when it was announced that eight of his buildings in the United States were named UNESCO World Heritage monuments. They are: Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois (1909); the Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago, Illinois (1910); Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin (begun 1911); Hollyhock House in Los Angeles, California (1921); the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House in Madison, Wisconsin (1937); Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona (begun 1938); Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania (1939); and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, New York (1959).

Frank Lloyd Wright Infographic

![10 Facts About Frank Lloyd Wright the Most Famous American Architect [Infographic]](https://mymodernmet.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/frank-lloyd-wright-famous-american-architect-infographic-my-modern-met-1.png)

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

You Can Virtually Tour 12 of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Most Famous Buildings

10 Attributes of a Successful Artist According to Frank Lloyd Wright

Designers Help Bring Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unbuilt Projects to Life

Architects Transform a Frank Lloyd Wright-Style Villa Into a Chic Tokyo Hotel