Galileo Galilei, astronomer and physicist, circa 1637, painted by Justus Sustermans. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The path of genius has not always been easy for those who walk it. When the work of the early modern astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei threatened the very ordering of the cosmos, he made a very powerful enemy in the Catholic Church.

The scientist was deemed heretical by the Inquisition and subject to extended house arrest. But these efforts were unable to stem the tide of heliocentrism: the concept, now common knowledge, that the Earth rotates around the sun at the center of our solar system. With the use of a revolutionary telescope he built himself, Galileo was able to observe celestial bodies in new ways. His work contributed to a paradigm shift which established him as a leading figure of the Scientific Revolution and the father of modern astronomy.

Crafting an Early Telescope

Galileo grew up in Pisa in the Duchy of Florence. At the University of Pisa, he became interested in mathematics and physics. His work on pendulums and his invention of the thermoscope were early achievements. He taught geometry and astronomy to students at the Universities of Pisa and Padua. At this time, the heliocentric view of the universe was in circulation as it was postulated by Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543. This disrupted the long-established Ptolemaic system which was geocentric; however, it was still very much a matter for scientific and religious debate. The revolutionary, even heretical, idea had yet to be proven.

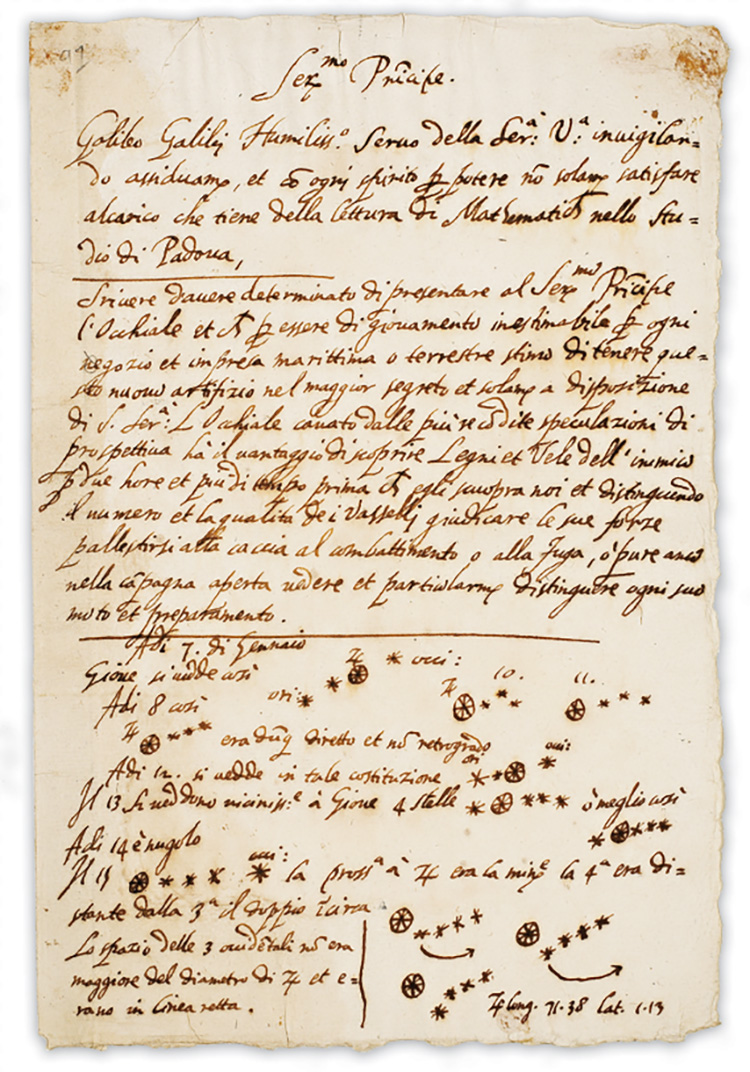

In 1608, Dutch spectacle makers Hans Lippershey and Zacharias Janssen, and Jacob Metius independently created the first known telescopes. Optics was a long-established science, and the principles of magnification behind the telescope were not new. The next year, Galileo caught wind of this “perspective glass” or spyglass. With vast experience creating scientific instruments, he set about making one of his own.

Galileo Perfects His Spyglass

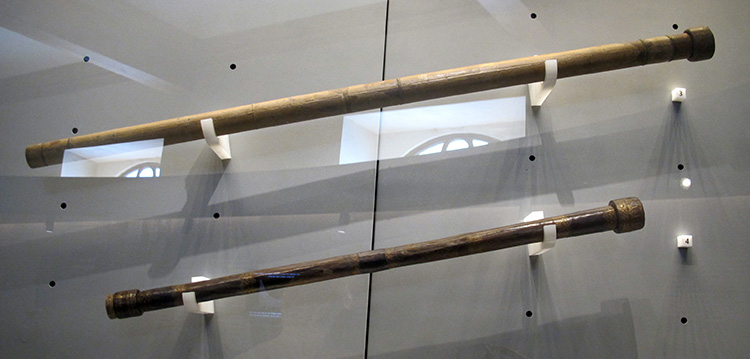

Galileo's telescopes on view at the Museo Galileo. (Photo: Sailko via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Dutch versions and Galileo's first attempt at a telescope possessed only a modest magnification power of 3X. However, by late 1609, Galileo had created a wood and leather version with 21X magnification. Another version, from 1610, possesses 16X magnification.

These early models had narrow fields of view but they offered a whole new way of looking at the universe. Before the telescope, the universe was studied by measurements taken with other instruments. Direct viewing of a phenomenon was usually limited to the abilities of the human eye. Galileo exhibited his inventions to Italian nobles and word quickly spread of his work.

“Galileo Galilei showing the Doge of Venice how to use the telescope,” by Giuseppe Bertini, 1858. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Galileo's telescopes were refracting telescopes. Here's how they worked: a concave and convex lens were connected by a long tube. A viewing lens eyepiece on the end of the convex lens allowed someone to see the refracted image.

This setup allowed for some shocking discoveries. Peering through his telescope, Galileo discovered that the moon is not a perfect sphere, that Jupiter has moons, Venus went through phases, and that the sun rotates. (Chinese astronomers had actually known of the sun spots Galileo observed for over a thousand years, but this fact was new to Europeans.) He published his discoveries and sketches of what he saw in space in a famous work entitled Starry Messenger. The moons of Jupiter and phases of Venus, in particular, proved to be important evidence in support of heliocentrism.

The Church and the Galileo Affair

Draft letter written by Galileo Galilei in August 1609 to Leonardo Donato, Doge of Venice, in which he offers his new telescope to his patron. The letter is currently held in the University of Michigan Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library's Special Collections. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Refuting geocentrism was still a bold scientific and social move in the early 17th century. Church and science were intimately entwined at the time. Many supporters of geocentrism relied literally on Biblical verses referencing the movement of the sun. However, the church was also a patron of scientific investigation and many learned priests were interested in the heavens, math, and other topics. Galileo, a devout Catholic, was not intending to overthrow religion. However, the period from about 1610 to 1633 came to be known as the Galileo affair in the history of the church.

By 1610, Galileo was actively defending heliocentrism in his correspondence and work. In 1615, a Dominican friar wrote to the Roman Inquisition complaining about Galileo's controversial stance. After an investigation of these charges of heresy, Galileo was not found guilty (yet). However, the Inquisition under Pope Paul V declared that heliocentrism was scientifically and theoretically wrong and prohibited the entire theory. Copernicus’s Revolutions and other books promoting the theory were banned. Galileo himself was personally warned.

When Pope Urban VIII was elected, Galileo was in the papal good books. His work comparing the geocentric and heliocentric models—entitled Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems—was published in 1632 with papal and Inquisition approval. However, it appears the church did not anticipate the true impact of the work. Presented in contrast, the merits of the two theories were unequal, despite what historians agree was Galileo's best efforts. Galileo found himself once more in front of the Inquisition which had authorized the book. This time he was found guilty of “suspected heresy” and denying scripture. Galileo, for his part, maintained he had not been a heliocentrist since its banning.

Galileo's Paradigm-Shifting Legacy

Galileo lived the rest of his life under house arrest, and he worked on kinematics and material science. Meanwhile, his heliocentric theories and use of the telescope—along with the work by contemporaries such as Johannes Kepler—had furthered both the theory and the study of astronomy.

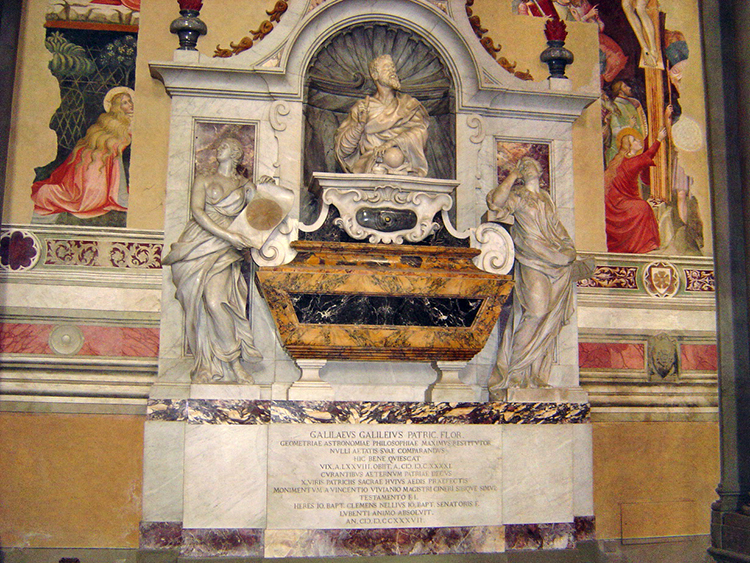

Galileo is considered a father of astronomy to this day. His works remained anathema to the church until the 18th century; with the unbanning of his works, his body was re-interred in a grand mausoleum in Florence. His designs and uses of the telescope remain one of his most important legacies. Today, you can view the telescopes at the Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy. To learn more, check out their entire website dedicated to Galileo's telescopes.

Tomb of Galileo Galilei in Florence. (Photo: stanthejeep via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Related Articles:

Meet the Harvard Computers, the Undervalued Women Who Mapped 400,000 Stars

Check Out 2021’s Best Milky Way Photography and Enjoy the Beauty of Our Galaxy

Amazing Restored Photos of Earth Taken by Apollo Astronauts

Who Was Marie Curie? Learn More About This Pioneering Nobel Prize Winner