“Night Forest” by Kimberly Throwbridge

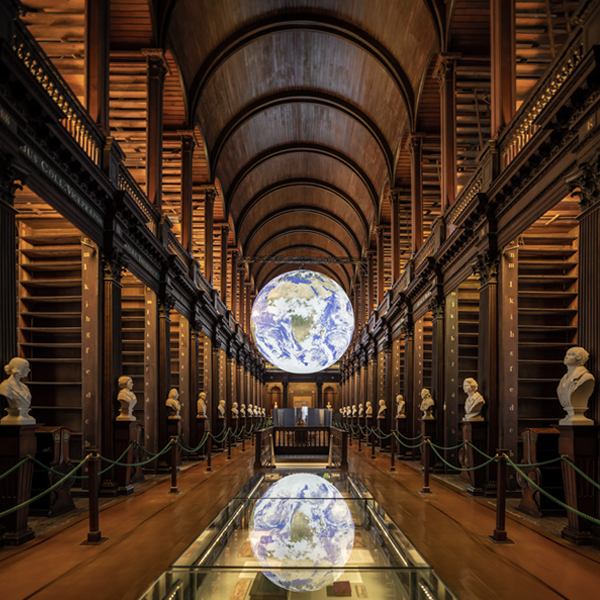

Art in hotels can often be an afterthought, a way to simply cover the walls rather than an avenue to engaging with guests. But not with Populus Seattle. The luxury hotel is set inside a restored warehouse in RailSpur, a micro-district within the city’s Pioneer Square neighborhood. It boasts beautiful rooms, tasty food and drinks, and an art program unlike any other. Its walls are lined with work by local artists, and everything you see there is for sale. Once a piece is purchased, the artwork is replaced with something new.

The Populus art collection is informed and shaped by the region in which it’s located, the Pacific Northwest (PNW). Works included were created by artists during a residency at RailSpur studios, next to the hotel. The collection is meant to grow over time, and each sale funds new commissions, allowing the program to support emerging artists and remain self-sufficient.

“The art program at Populus Seattle is exceptional for so many reasons,” says Eugene Kim, editor-in-chief at My Modern Met, who had the opportunity to visit the hotel this past summer. “Each piece is created on-site, giving artists a rare opportunity to both showcase and sell their work while contributing to the beauty of this carbon-positive hotel. It’s clear that extraordinary thought and care went into building such a forward-thinking art program—and hotel.”

Populus’ unique collection is made possible through a partnership with ARTXIV and developer Urban Villages. ARTXIV is led by Dominic Nieri and is a global art production house and creative strategy agency making good on its mission to integrate compelling artistic narratives into the built environment. It aims for work to be enriching and not a passive experience; in doing so, new voices grow.

Art was, and remains, a fundamental building block of RailSpur. “Pioneer Square has always been Seattle’s creative district, but its future felt fragile,” Nieri tells My Modern Met. “Our goal wasn’t just to fill space. It was to design a cultural engine that worked with the community rather than for it, a framework where artists and neighbors could remain embedded in the life of the district.”

Within Populus Seattle, one work you might see is Night Forest by Kimberly Throwbridge. Her massive painting features a woodland scene at dusk with an owl perched on a branch and a coyote slinking along the forest floor. There’s a dramatic interplay of light and shadow, creating an abstracted aesthetic that feels almost Cubist. The entire collection catalog can be viewed through ARTXIV.

My Modern Met had the opportunity to speak with Nieri about how ARTXIV began, developing RailSpur, and why he likes working with artists in the PNW. Scroll down for our exclusive interview.

“We Walked to the Top of the Mountain in Search of Miraculous Things by if Nothing Else the Thin Air Made Us Catch Our Breath Between Steps” by Andrea Heimer

What is your background? How did you begin working with artists, galleries, and museums in the way you do now?

I studied fine art at Oregon State University and opened a gallery in Pioneer Square in 2015. Almost right away, I felt the traditional gallery model was broken. The internet and social media were already shifting power toward artists, and I kept wondering if galleries were actually serving them, or just holding onto a hierarchy that kept themselves relevant. The old structures didn’t reflect how artists could now interact with the world.

At the same time, I was producing public art projects and mural festivals across the U.S. and abroad. Those projects ran on a very different economy. They didn’t offer much financial reward, but they gave artists real creative freedom and unique experiences. In that setting, artists pushed their practices further than institutions usually allowed, and communities formed through shared encounters. People came together, exchanged ideas, and built relationships that lasted long after the work was done. It showed me that authentic community doesn’t come from structure alone. It has to be lived and built in real time.

Later, I joined Meta Open Arts and produced more than 300 site-specific installations across North and South America. It was almost the opposite of the festivals. Artists suddenly had resources, institutional backing, and financial reward. Inside the offices, creativity stretched into things that once felt impossible. But outside, those same buildings often signaled displacement to the communities around them. What felt like cultural investment on the inside was often experienced as cultural loss on the outside. That contradiction made it clear there needed to be another approach—one where artists were resourced, but also remained permanent contributors to the life of a place.

That became ARTXIV. I didn’t want to build another gallery or consultancy. I wanted to create a collaborative organization that worked in true partnership with artists. ARTXIV is a connective layer. It makes sure artists aren’t limited by exclusivity and that they have the resources to realize their vision without compromise. We work alongside them at every stage, from concept and curation to production, documentation, and presentation. And just as important, we think about how the outside world interacts with artists. We build equity into projects so their contributions are valued, and we make sure their visions are understood and realized, not compromised to meet external concerns. Whether a project is self-produced or created for an institution, the artist’s voice stays central.

“Garden Sequence 070624” by Przemyslaw Blejzyk

“My Summer So Far” by Sean Barton

What is your favorite thing about what you do?

What I love most about this work is the freedom it creates, not just for artists, but for everyone involved in shaping an experience. For me, it’s about seeing ideas that once felt impossible actually come to life, and knowing that each project leaves behind the conditions for the next one. My experiences showed me how freedom fuels discovery and how resources fuel scale. ARTXIV is about holding both at once, and proving that when artists are trusted with freedom and support, the outcome is stronger than anything one person could have predicted on their own.

“Oblate Spheroid” by Devin Liston

“The Party is Behind Us” by Matthieu Pommier

How do you find artists to work with and feature?

I’m drawn to creativity that feels unsettled, when someone is still asking questions rather than presenting answers. That energy isn’t limited to artists. Some of the most meaningful projects I’ve been part of have come from curators, producers, or even developers and city planners who are willing to share in the risk of discovery. It’s less about chasing finished ideas and more about recognizing when someone is pushing into uncharted territory.

Collaboration is central to that. Gage Hamilton from Forest For The Trees has been one of my closest partners. His intuition as both an artist and curator balances my focus on systems and process, and together we’ve created conditions that allow new voices to grow.

That is the spirit behind ARTXIV. We build frameworks strong enough to hold risk so that fleeting discoveries don’t disappear. Instead, they accumulate into something lasting. In that way, finding artists is not just about selection. It’s about trust—trusting that if you build the right conditions, creativity will surface in ways no one could fully predict on their own.

“Canoe Journey” by Joe Feddersen

“Plant Fantastic” by Patty Haller

How did you get connected with the RailSpur project?

RailSpur began in 2021, in the quiet of COVID. Henry Watson invited us to activate an empty ground-floor space in a vacant building in Pioneer Square. We began by asking questions, and those questions led to an eight-story exhibition during the Seattle Art Fair just two months later, an exhibition that featured more than 200 artists and welcomed over 15,000 visitors in just four days. It also marked the launch of Forest For The Trees in Seattle.

Pioneer Square has always been Seattle’s creative district, but its future felt fragile. Our goal wasn’t just to fill space. It was to design a cultural engine that worked with the community rather than for it, a framework where artists and neighbors could remain embedded in the life of the district.

Most new developments don’t make that possible. Too often, the creative community is brought in as decoration at the end of a project, or used as a temporary placeholder until something more profitable arrives. Urban Villages ethos was different. Henry and the entire team approached art and community as infrastructure from the beginning. They gave us the trust and resources to experiment at a moment when the world felt uncertain, and that commitment set the tone for everything RailSpur could become.

“Night Forest” by Juliet Shen

“Love, and Lost” by Amy Bay

What has been the most rewarding part of the endeavor?

The most rewarding part has been proving that the built environment endures when it is rooted in authenticity and connection, when relationships and experiences are valued as much as products. RailSpur shows that development can honor history while shaping a sustainable future, ensuring that artists, culture, and community remain at the heart of the neighborhood long into the future.

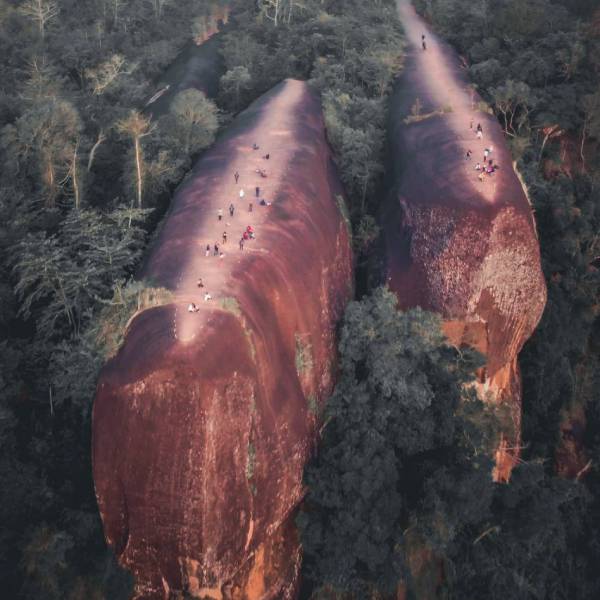

“Moving Mountains” by Cristina Martinez

“Reclamation” by Claire Putney

Can you tell us about the Populus Art Collection and what makes it unique?

In most hotels, art is an afterthought, outsourced to consultants who fill walls with safe, generic work. With Populus, we wanted to take a different approach: treating art as infrastructure and building it into the identity of the place from the very beginning.

To do that, we turned 10,000 square feet of the RailSpur Manufacturers Building into a production studio and invited more than 30 artists into a three-month residency. Instead of acquiring finished works, we asked them to create in direct response to the building, the neighborhood, the natural world and the city. Out of that came hundreds of new pieces that reflect a region in motion, rooted in the environmetal landscape yet shaped by the energy of an evolving urban city.

The collection itself is designed to evolve. Every piece is available for acquisition, and when one leaves, it is replaced by a new commission created on-site. Collectors aren’t just taking home art, they’re helping sustain the next wave of artists and ensuring the collection continues to provide more opportunities for artists in the future.

That ongoing cycle is what makes the Populus Collection unique. It’s not a static display, but a living framework where creativity, place, and community remain in constant dialogue.

“Otherside Of” by Pajtim Osmanaj

Becca Fuhrman

What do you love about the artwork and artists in the Pacific Northwest?

The Pacific Northwest feels like a proving ground. It has a history of experimentation but is free from many of the entrenched systems that weigh down older art capitals. That openness creates space for new models to take shape in real time, and artists here are unafraid to test them.

What I love most is the balance they hold. The artists of this region are deeply tied to place, yet restless enough to push outward. They draw from the landscape and history, but they don’t stop there. They adapt, remix, and stretch those influences into something new. Combined with a city still defining its cultural identity, it creates fertile ground for innovation.

At a moment when culture everywhere feels pulled toward convenience and disconnection, Seattle has the chance to move differently, to lead not by imitation, but by authenticity and connection. Those are the qualities that endure, and the ones ARTXIV is working to cultivate.

“The Haul of Industry” by Joe Nix

“Izzy Bouquet” by Baso Fibonacci

My Modern Met had the chance to chat with Dominic Nieri while visiting Populus Seattle. Check out the video interview below.

View this post on Instagram