“Nose to Nose” by Douglas Gimesy

Human/Nature Winner

“Since 2006, developers have constructed dozens of new subdivisions on the outskirts of Melbourne, Australia, transforming bushland that once sheltered kangaroos, wombats, flying foxes, and other wildlife into tidy suburban streets. As the built environment encroaches on the wild, a growing number of displaced animals are struck by cars. Those that survive might, if lucky, find themselves in the care of a wildlife rehabilitation shelter like the Joey and Bat Sanctuary near Melbourne.

Photographer Douglas Gimesy was documenting work at the sanctuary last year when he met a bare-nosed wombat (Vombatus ursinus) whose mother had been killed by a car. A good samaritan had thought to check the dead marsupial’s pouch and found the four-month-old joey inside, still alive.

Gimesy watched a young veterinary student bottle-feed the orphaned wombat. When the feeding was over, the student touched her nose to the joey’s in a tender moment of interspecies bonding. Wombats’ sense of smell rivals that of bloodhounds, and scientists believe that the animals use their sophisticated noses to navigate at night and sniff out the poop of other wombats. Perhaps because her nose is so sensitive, Gimesy said that the baby wombat in this photograph seemed to especially enjoy the sensation of skin-to-skin—or nose-to-nose—contact.”

Some of the world's top nature conservation photographers came together to judge the California Academy of Sciences’ renowned BigPicture Photography Competition. Cristina Mittermeier, Suzi Eszterhas, and Ami Vitale are just some of the big names that weighed in on the final decision. The winning photographs are both a testament to our world's biodiversity, as well as the unique challenges it is currently facing.

Corey Arnold, who was named the Grand Prize winner, has a unique perspective on nature. As both a commercial fisherman and a photographer, he often explores the complex relationship between man and nature. Whether showing a lone coyote scurrying over a pedestrian bridge in Chicago or an American black bear hanging out on someone's back porch, Arnold's winning photo story is an interesting peek at how humans and animals co-exist.

Many of the other winning photos celebrated the touching relationships that can develop between humans and animals. Douglas Gimesy showed a moment of tenderness between a veterinary student in Australia and an orphaned baby wombat. This special glimpse at bonding is a touching tribute to the work that wildlife rehabilitation centers do.

Halfway around the world in the Democratic Republic of Congo, another caretaker is making sure that her charges are getting all the love they deserve. In Marcus Westberg‘s winning photo, orphaned chimps cling to their primary caregiver just as a baby would. This intense bond makes sense when one realizes that chimpanzees typically stay close to their mothers until they reach 5 years old. When mother chimps are killed by poachers, workers at the Lwiro Primate Sanctuary in Kahuzi-Biega National Park step in to make sure to fill the void.

“To view humans as entirely separate from other species… is both morally and factually wrong,” shares Westberg. “We are more similar than we realize.”

To dive even further into the natural world, scroll down to see a selection of the winning photographs. Hopefully, they provide inspiration and action to help preserve the sanctity of nature.

These images originally appeared on bioGraphic, an online magazine about nature and regeneration and the official media sponsor for the California Academy of Sciences’ BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

The winners of the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition embrace our world's biodiversity.

“Coyote Crossing” by Corey Arnold

Grand Prize Winner

“How did the coyote cross the road? If the coyote (Canis latrans) is among the 4,000 or so living in the Chicago metro area, the answer may be that it used a bridge to avoid being hit by a car. Across the United States, motor vehicle collisions are responsible for at least a million vertebrate deaths per day, and Chicago is no exception: Windy City coyotes typically live only about three years, compared to 10 years on average elsewhere in the wild and up to 18 years in captivity. Their most common cause of death is being struck by a car.

But like many wild animals living in densely populated urban environments— including those featured in Corey Arnold’s Grand Prize-winning photo story—coyotes have found ingenious ways to coexist with humans. In Chicago, where Arnold tagged along with scientists from the Cook County Urban Coyote Research Project, coyotes regularly use train trestles like this one to circumvent busy highways. They also shift their normal behavioral patterns to hunt mostly at night, when they’re less likely to encounter humans, and they seem to avoid trash in favor of Chicago’s live deer, rabbits, and rodents. Radio-tracking data from the Research Project’s studies has shown that even in America’s third-largest metropolitan area, coyotes and humans overlap on a daily basis—a testament to these canids’ remarkable tenacity, even after centuries of persecution across the United States.”

“Life on the Edge” by Amit Eshel

Terrestrial Wildlife Finalist

“Nubian ibexes (Capra nubiana) live on the knife edge of survival, in deserts with scant vegetation and harsh climates. They also live at the literal edge of cliffs, with little but space and steep drops for company. Such vertiginous topography helps deter predators like leopards and wolves; in Israel’s Avdat Nature Park, scientists have watched Nubian ibexes leave their newborns on cliff outcroppings too precipitous for most mammals to reach, then return for feedings until the young grew agile enough to traverse the sheer cliffs on their own.

Males of the species grow backward-curving horns that can be more than a meter (up to 4 feet) long. They use these impressive weapons to defend against predators and to compete with others for breeding rights, as photographer Amit Eshel captured in this image of two clashing males in Israel’s Zin Desert. Despite the violence of such encounters and the precarious stage on which they’re fought, male ibexes rarely to tumble to their death; the wild goats’ agility, speed, and comfort with the abyss seem to protect them even in the heat of battle.

Yet while the Nubian ibex’s ability to navigate steep terrain may protect it against natural predators and rival males, it’s proven little solace against the encroachment of humans. Ancient cave drawings and bone remnants suggest Nubian ibexes once ranged throughout the mountains of northeastern Africa and the Middle East. Today, only 5,000 or so cling to life in fragmented populations scattered across Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Arabian Peninsula. The healthiest populations are in Israel— though part of the reason for their success is that the Arabian leopards (Panthera pardus nimr) that once preyed on ibexes have been largely extirpated from the country.”

“Stunning Cephalopod” by Heng Cai

Aquatic Life Finalist

“In addition to being visually mesmerizing, the iridescent symmetry of this blanket octopus plays a key role in the cephalopod’s success as a predator. Four species of blanket octopuses (genus Tremoctopus) roam tropical and subtropical seas—including the Gulf of Mexico, the Indian Ocean, the Great Barrier Reef, and the Mediterranean—searching for fish and crustaceans to eat.

Most observations of blanket octopuses come from females, like this one photographed in the Philippines. Females can grow up to 3 meters (6 feet) long—more than 40,000 times larger than the walnut-sized males—and sport a characteristic fleshy “blanket” draped over their tentacles, which makes them appear even larger. If threatened, a female can shed her blanket in an instant to distract her predator and escape, then grow a new one. She’ll also squirt ink, change color, and generally outsmart and out-maneuver fellow ocean dwellers until she can mate and lay thousands of eggs.

What really sets these cephalopods apart, however, is a unique hunting method: Because blanket octopuses are immune to jellyfish toxins, they commonly tear an arm off a jellyfish or even a Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis), then carry around the severed appendage to use as a weapon for stunning prey.”

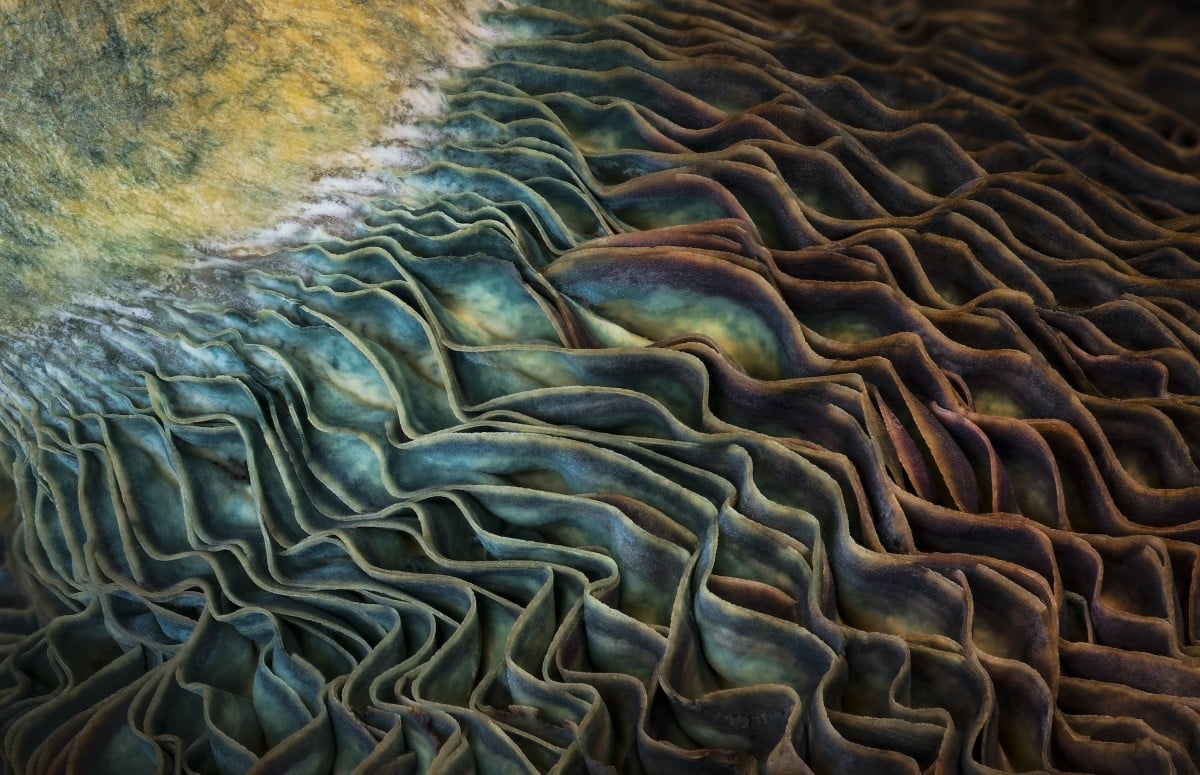

“Magical Mushroom” by J Fritz Rumpf

Art of Nature Winner

“Is it waves crashing onto shore? A landscape of furrowed canyons? The topography of a distant planet? People seeing J Fritz Rumpf’s photograph for the first time have transposed all kinds of fantasies onto its hypnotic patterns, but no one, Rumpf says, has correctly guessed what they’re looking at: the gills of a fungi from the genus Lactarius, better known as milk cap mushrooms for the milky, latex-like liquid they ooze when cut.

Rumpf was foraging for mushrooms in Arizona’s White Mountains one August afternoon when he picked up this one. Unsure if it was edible, he returned it the forest floor—and happened to notice the colors of its gills. Of the dozens of species of milk caps that grow in the American Southwest, many “bruise” when chemicals in their fruiting bodies are exposed to air, turning them the murky blue-green that caught Rumpf’s eye.

Milk caps work their magic in other ways as well. In the subterranean world below forests, their fungal filaments—called mycorrhizae—form a net of cells that grows with and around tree roots. Milk cap mycorrhizae help their host trees access water and nutrients, and they obtain carbohydrates in return. As scientists learn more about this symbiotic relationship, they’re uncovering the multitude of ways that milk caps and other fungi are essential to the health of forests and other ecosystems around the world.”

“All My Children” by Marcus Westberg

Human/Nature Finalist

“Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) share nearly 99 percent of their DNA with human beings. At the Lwiro Primate Sanctuary in Kahuzi-Biega National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, this genetic bond is perhaps reflected in the relationships that form between orphaned chimps and their human caregivers. Wild chimps typically stay close to their mothers until they’re about 5 years old, so when a mother is killed by poachers, the separation can cause irreparable harm for young, developing chimps. Many of the orphaned chimpanzees brought to the sanctuary by Congolese wildlife officials arrive carrying both physical and emotional wounds.

The healing at the sanctuary goes both ways: Some of the caregivers who feed, cuddle, and help rehabilitate chimps are themselves victims of sexual abuse who have found independence and employment working with chimpanzees. Photographer Marcus Westberg, who spent weeks at the sanctuary, said that caregivers treat the chimpanzees as tenderly if they’re human children, and the young chimps, likewise, often act like kids—alternately playful, mischievous, and vulnerable.

Our genetic and ecological connections to other creatures extend beyond the great apes—and arguably our care should as well. ‘To view humans as entirely separate from other species… is both morally and factually wrong,' said Westberg. ‘We are more similar than we realize.'”

“Spotted” by Donglin Zhou

Terrestrial Wildlife Winner

“At first glance, this might seem like a mother snow leopard (Panthera uncia) playing with her kitten, but a closer look reveals a lack of distinct spots on the cloudy fur of the smaller cat. The fully-grown feline is actually a Pallas’ cat, or manul (Otocolobus manul), a housecat-sized wildcat whose range across Central Asia overlaps with the mountains, steppe, and high deserts favored by its better-known cousin, the snow leopard.

Despite sharing a similar predilection for cold climates and high altitudes, there’s scant scientific evidence of snow leopards preying on Pallas’ cats. So when photographer Donglin Zhou saw a snow leopard stealthily approaching a mother Pallas’ cat on the Quinhai-Tibet Plateau, she was astonished. “Both species are hard to see at any time,” she said. “Let alone together.”

Oblivious to the snow leopard creeping up behind her, every fiber of the Pallas’ cat’s body was focused on hunting plateau pikas (Ochotona curzoniae) for the two-month-old kittens waiting in a nearby den. Zhou had spent days watching the mother cat feed her kittens, and was devastated to see the doting mother snatched by a snow leopard. Upon seeing her in the leopard’s jaws, she said, “the tears cannot stop coming into my eyes.”

After the snow leopard left the scene, Zhou, her guide, and forest rangers decided to leave some roadkilled pikas outside the den for the three kittens. For three weeks, they guarded and fed the kittens, until the tiny Pallas’ cats were ready to leave the safety of their den and begin to fend for themselves, stalking pikas and dodging danger on the wild, windswept plateau that had already claimed their mother.”

“Catch Me If You Can” by Xiaoping Lin

Winged Life Winner

“As a member of the heron family, the little egret (Egretta garzetta) is typically a stealthy hunter, standing still in shallow water or waiting in a roost for unsuspecting fish to swim by. Or the bird shuffles its yellow feet to scare up prey, which it then pierces with its sharp beak. This egret in a lake near Xiamen, China, however, was caught off-guard when the small fish it had been eyeing was chased clear out of the water—by a much larger fish.

Photographer Xiaoping Lin used high-speed continuous shooting to capture the startled egret as it lifted off above the churning waves. The resulting image of fleeting action permanently frozen in a palette of whites and silvers is “like a poem,” Lin said.

Indeed, egrets have featured in Chinese poetry since at least the 11th century BC. They appear three times in the first known collection of Chinese poetry, the Shih ching; for centuries afterward, poets compared them to snowflakes and frost and used them as symbols of purity and impermanence. Despite this reverence, some species of egret were hunted to the brink of extinction or local extirpation in the 19th century in pursuit of their fashionable plumes. Today, although the little egret’s population is stable, species such as the Chinese egret (Egretta eulophotes) are still struggling to rebound amidst ongoing habitat loss.”

“Blades and Spines” by Kate Vylet

Aquatic Life Winner

“The familiar story about sea urchins and kelp forests goes like this: First, sea otters that eat sea urchins were hunted nearly to extinction along much of the West Coast. Then, in the 2010s, sea star wasting disease killed off urchin-slurping sunflower stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides), causing sea urchin population to explode. Marine heat waves also took a heavy toll on giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera). Together, these factors left desolate “urchin barrens” where lush undersea forests had once thrived. Between 2008 and 2019, some 95 percent of kelp forests disappeared from Northern California.

Conservationists are now trying a variety of tactics to revive the lost forests, from breeding sunflower stars in captivity to designing an urchin-smashing robot to enlisting scuba divers to harvest urchins. Conservation photographer Kate Vylet, however, is troubled by the narrative that sea urchins are the bad guys in this story. “Urchins belong to the kelp forest as much as the kelp itself does,” Vylet said.

Vylet was swimming back to shore one day after diving in a thriving kelp forest off the coast of Carmel Bay, California, when she saw a blade of loose kelp being devoured by purple (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) and red (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) sea urchins. To her, it illustrated the role urchins can still play in a balanced ecosystem, and she set up her camera to capture nature at work in all its complex ebbs and flows.”

“Regeneration” by Miquel Angel Artús Illana

Landscape, Waterscapes, and Flora Winner

“Like many ecosystems in the western half of North America, many forests in Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada, benefit from naturally occurring, low-intensity wildfires. Fires replenish soil nutrients, keep forests from becoming homogenous, and spur the growth of berry bushes that grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) and other wildlife love to munch. Yet beginning in 1913, park managers have actively suppressed wildfires; across the 92,000 hectare (227,000 acre) park, only eight fires in the 20th century grew larger than 40 hectares before firefighters extinguished them. Land managers across Alberta adopted similar practices.

Without fire, trees grew unnaturally dense, and dead logs accumulated on the forest floor. Beetle infestations swept through Alberta in the 2010s, leaving more than 2.4 million hectares (nearly 6 million acres) of lifeless, standing trees.

As all this dead timber collides with the hotter, drier conditions wrought by climate change, abnormally large and intense wildfires have exploded. This spring, for instance, smoke from gigantic Alberta wildfires stretched across the continent. And while fire-adapted forests can recover from low-intensity wildfires, research from across the Rocky Mountains has shown that tree seedlings struggle to take hold in the wake of mega-fires.

Today in Jasper National Park, as elsewhere in western North America, forest managers are trying to reverse a century of misguided management by igniting controlled burns and letting some wildfires burn. The resulting landscape may look different than the swaths of green spruce and pine that many park visitors are accustomed to, but as this haunting image of a burned spruce forest shows, they can be equally captivating.”