“Bee Balling” by Karine Aigner. Grand Prize Winner.

“On a warm spring morning in South Texas, a female cactus bee (Diadasia rinconis) emerged from her small, cylindrical nest in the ground, rising like ash from a chimney. Almost instantly, she was swarmed by dozens of patrolling males, their tawny bodies forming a buzzing, roiling “mating ball” as they vied for a chance to copulate with her. After a tumultuous 20 seconds or so, the ball of bees dissipated, and the female flew off—a single, victorious male holding tight to her back.

Mating aggregations only last for a little more than a week, so photographer Karine Aigner was fortunate to capture this particular mating ball. While rarely noticed or documented by humans, these native bees play a critical role as pollinators, especially for prickly pear (Opuntia spp.) cacti, a critical source of sustenance for many species in the dry American Southwest.”

The annual BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition has just released the winners and finalists for 2022. As always, the California Academy of Sciences puts together the event to celebrate Earth's biodiversity. This year's big winner, Karine Aigner, took home the top prize for a rare look at the bizarre mating ritual of cactus bees.

Hers is just one of many photographs in the contest that document exceptional behavior by animals, whether they are on land or under water. For example, Jose Grandío's image of an acrobatic stoat is a charming example of behavior that scientists are still trying to understand. Whatever the reason for this “dancing,” what is clear is that we are lucky to have photographers like Grandío who are willing to take the time to immortalize these flips and leaps.

Whether exploring mating rituals or looking at how animals are adapting to human development, all of the photographs celebrate the natural world. And, at the same time, they teach us about what is really happening in the animal kingdom. So while appreciating the artistry of these photographs, we are also pushed to learn more about how animals are thriving or struggling and what we can do to help.

This gallery was originally published in bioGraphic, an independent magazine about nature and conservation powered by the California Academy of Sciences, and media partner of the BigPicture Natural World Photography Competition.

The winners of the 2022 BigPicture Natural World Photography Contest celebrate nature and its biodiversity.

“The Stoat’s Game” by Jose Grandío. Terrestrial Life Finalist.

“In the pre-dawn hours of a cold winter morning in the French Alps, photographer Jose Grandío lay still in the snow, waiting for a stoat (Mustela erminea) to emerge from its burrow. He had spent the past few days waiting in the same manner, without payoff, but his patience was about to be rewarded. Shortly after the sun rose, the stoat climbed out into the pale, winter light and proceeded to put on a spectacular show. “He seemed to be playing with the fresh snow that had just fallen, making sudden jumps and crawling through the snow,” recalls Grandío.

Scientists have witnessed stoats engaging in similar displays on many occasions, and they refer to the behavior as dancing, although their opinions are divided about what motivates the leaps and twists. Sometimes, the dances are performed in front of a rabbit or large bird in a seeming attempt to confuse or distract potential prey—a strategy that has proven effective in a number of documented interactions. At other times, as was the case in the display Grandío photographed, there is no prey animal in sight, and the dance seems simply to be an expression of exuberance. A third hypothesis is that the dances are actually an involuntary response to a parasitic infection, since stoats are known to be hosts for cranial parasitic worms. Whatever the interpretation of the behavior, one thing scientists have learned is that when associated with an attack on a large prey species, these displays reduce the risk of injury to the stoat—likely because they provide an element of surprise. Such a benefit could eventually reinforce the behavior, whether it was originally intentional or not.

In this particular case, the stoat leapt and danced for about half an hour before returning to his den for the rest of the day. While the impetus for his energetic display is unclear, Grandío can’t help thinking it was “something like a game for him,” a joyful response to the pleasure of pristine snow.”

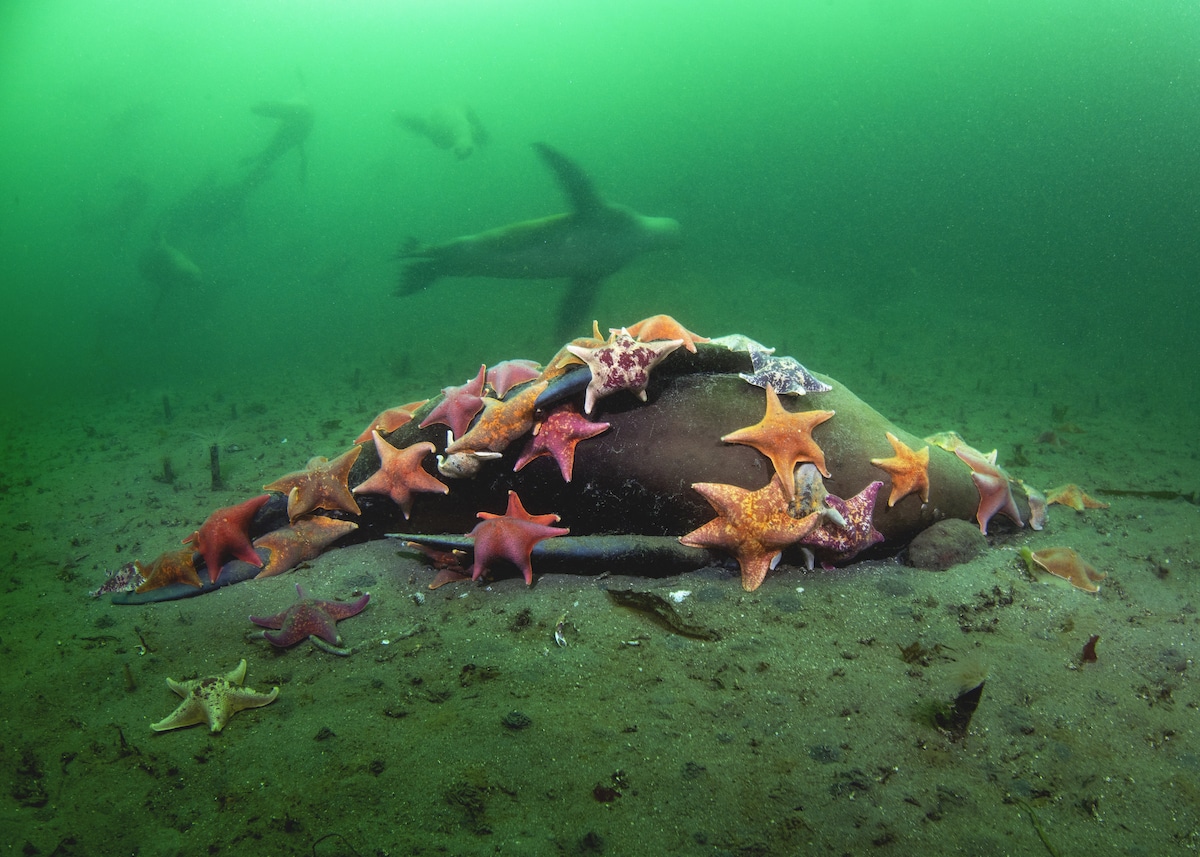

“After the Fall” by David Slater. Aquatic Life Winner.

“California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are iconic members of the Monterey Bay ecosystem, and photographer David Slater loves diving with them. “They rush past you with such beauty and grace that they leave you stunned,” he gushes. But during a dive last September, Slater witnessed a more somber sea lion scene. On a mucky stretch of sea floor, a dead sea lion had fallen to its final resting place, a colorful array of bat stars (Patiria miniata) strewn across its body like flowers tossed onto a grave.

Bat stars are omnivorous and frequently feed on carcasses that fall to the ocean floor.”

“Tunnel Vision” by Tom Shlesinger. Aquatic Life Finalist.

“Each year, from August to early October, Atlantic goliath groupers (Epinephelus itajara) gather off the east coast of Florida to spawn. On dark nights when the moon is new, refrigerator-sized males produce low-frequency booming sounds by contracting their swim bladders, calling other groupers to congregate around shipwrecks or rocky reefs. Fifty years ago, more than 100 fish might answer the call. But by 1990, the slow-moving species had been fished almost to extinction, and mating aggregations were often reduced to just a handful of fish. That year, goliath groupers were protected under both federal and state fishing bans, and the population slowly began to recover. While Florida’s mating aggregations have not yet attained the numbers local fishermen recall from the 1970s, it’s now common to see 20 to 40 groupers together during the breeding season.

However, in March, despite heavy opposition from scientists who study the species, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission voted to reopen recreational fishing for goliath groupers beginning in 2023. Under the new plan, up to 200 permits will be sold each year for between $150 and $500, each of which will allow for the harvest of an adult grouper.”

“Face to Face” by Fernando Constantino Martínez Belmar. Human/Nature Finalist.

“Two creatures face off through a woven-wire fence: one predator the other prey; one wild, the other, essentially, manufactured for our use. The moment is a manifestation of two worlds colliding, with no clear indication of which will prevail. Such images, of the natural world intersecting with one so heavily impacted by humans, have become a near obsession for Mexico-based photographer Fernando Constantino Martínez Belmar. And few places in the world present as many opportunities to capture the conflict first-hand as Martínez Belmar’s native Yucatán Peninsula, home to both the elusive jaguar (Panthera onca) and one of Mexico’s fastest-growing tourist hotspots, the “Maya Riviera.”

Until recently, scientists had little hope that a viable ecological corridor could exist between the two protected areas, given the heavily developed land that links them. However, a radio tracking study published earlier this year suggests that jaguars are not only using this corridor—they are establishing home ranges along its route. While the cats prefer forested or secondary growth areas over profusely disturbed habitat, they are capable of capitalizing on opportunities presented by human development. One male, for instance, centered his home range on a landfill, where he found a plentiful source of prey in the form of feral dogs and other animals that scavenged at the site. It’s not an ideal scenario, but the resilience demonstrated by these individuals provides hope that with thoughtful planning around future development in the area, the Yucatán Peninsula’s jaguars can continue to thrive.”

“Frame Within a Frame” by Sitaram May. Winged Life Winner.

“Photographer Sitaram May used to think of wildlife photography as something he did while traveling. But when the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe, he started to pay more attention to the wildlife in his own backyard. “One night, sitting on my balcony, I was looking out at a custard apple tree, and bats were coming frequently to eat the fruits,” he recalls. “The whole world was cursing bats, but I decided to observe them.” May spent three weeks watching the fruit bats, eventually learning to predict their behavior and identify gaps in the tree canopy where they were likely to make an entrance. At one such opening, he managed to capture this shot, perfectly framing the bat within a ring of lush, green foliage.”

“Spider Web” by Bence Máté. Terrestrial Life Winner.

“It was dawn in Hungary’s Kiskunsag National Park, and photographer Bence Máté lay still, barely breathing, on a coffin-sized floating hide. In front of him, a Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) was busy gnawing on a tree, backlit by the first rays of the morning sun. Nearby, previously felled trees emerged like dock pilings from the mist-shrouded water, one of them festooned with a glowing spider web. The ethereal scene was more than just beautiful; it was a striking illustration of the idea that beavers transform their environments when they build dams, creating habitats that are utilized by many other species.”

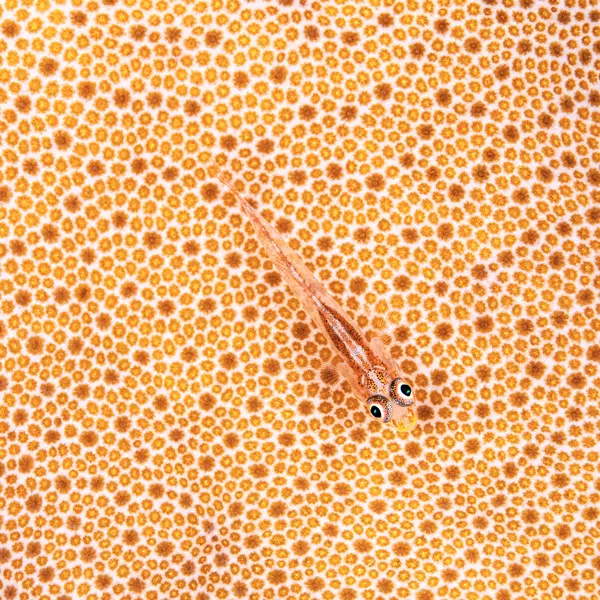

“Shooting Star” by Tony Wu. Aquatic Life Finalist.

“Three days before the full moon last July, photographer Tony Wu dove into a bay off the coast of Kagoshima, Japan, in search of a starry goby (Asterropteryx semipunctata)—a golf-tee-sized fish with bright, pin-prick dots scattered across its dark skin. He had been hoping to photograph the pretty, star-studded fish for weeks, and he expected to spend his whole dive focused on that task. But shortly after he spotted his first goby, Wu got sidetracked by a different stellar scene: A Leach’s sea star (Leiaster leachi) raised itself up onto the tips of its arms and began to spawn, shooting a Milky Way of sperm into the surrounding seawater.

Like many marine invertebrates, starfish reproduce by broadcast spawning—releasing large quantities of sperm and eggs into the water column within a short period of time. To maximize the chances of fertilization for these gametes, they synchronize their efforts with neighboring members of their species, using temperature, light, and lunar cycle cues to guide their timing.”

“Embryology” by Jaime Culebras. Terrestrial Life Finalist.

“On a moonlit night near the Yanayacu Research Station in northeastern Ecuador, a female Wiley’s glass frog (Nymphargus wileyi) hopped onto a fern and traversed one of its fronds, responding to the call of a waiting male. He mounted her back, prepared to hold on tight for several hours until she was ready to deposit her eggs. Finally, she positioned herself at the tip of a leafy arm that extended over a stream and pushed out a clutch of eggs, which the male immediately fertilized. Housed within a gelatinous mass that deters predators, protects against dehydration and prevents fungal infections, the embryos developed for a few days on the tip of the fern before dropping into the water to continue their metamorphosis. But before they fell, scientist and photographer Jaime Culebras captured this stunning, backlit portrait.

Very little is currently known about Wiley’s glass frogs. They weren’t documented by scientists until 2006, and so far, they have only been found in the immediate vicinity of the Yanayacu Research Station. While researchers have collected adults and seen their egg clutches, which contain between 19 and 28 embryos, they have never recorded the species’ mating calls, documented parental investment behaviors, observed the tadpoles, or conducted a population assessment.”

“Into the Light” by Pål Hermansen. Art of Nature Winner.

“When photographer Pål Hermansen walked outside one brisk March morning in Ski, Norway and looked back at his house, he was dismayed. One of the outdoor lights had been left on all night, and within its bright shell, he saw the dark stains of dozens of insects, drawn to their death by the accidental beacon. As he cleaned out the fixture, Hermansen was inspired to photograph the collection of insects, hoping to shine a light on ‘the hidden creatures that are a foundation for our lives—creatures that we easily ignore.'”

“Sickening Delicacy” by Bence Máté. Human/Nature Winner.

“While traveling in Romania’s Carpathian region several years ago, photographer Bence Máté came across a horrific scene. At a spawning site for common frogs (Rana temporaria), hundreds of frogs (and several toads) lay dead in the water, some still grasping partners, their hind legs notably missing. Poachers had plucked the amphibians from the pool as they attempted to breed, cut off their back legs to feed the frog-leg trade, and thrown them back into the water to die a lingering death among their spawn. ‘It was the cruelty that shocked me most,' says Máté, ‘but also the harm caused to local populations.'

Every year, millions of frogs are traded around the world as a source of food. The trade is fueled not just by the collection of wild animals on a local scale, as Máté witnessed in Romania, but also by industrial commercial farming in China and other countries. While poaching can imperil local populations, commercial farming actually poses an even greater threat to amphibians around the world. ‘Mass farming and international trade to supply the frog-leg industry are spreading deadly diseases and contributing to the current amphibian extinction crisis,' says herpetologist and wildlife trade expert Jonathan Kolby. ‘Two types of pathogens in particular, amphibian chytrid fungus and ranavirus, are being spread far and wide by the trade in frog legs and have already driven dozens of population declines and extinctions.'

If frog legs are to stay on the menu for humans, improved welfare and disease control measures are urgently needed to better protect amphibians globally.”

“Hidden Beauty” by Tom St George. Landscapes, Waterscapes, and Flora Winner.

“Deep in a cenote on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, photographer Tom St George encountered this otherworldly, seemingly lifeless cavern, its dimly lit waters penetrated by thousands of dramatic stalactites. Inhospitable as it may appear, this flooded cave is actually far from barren. It is part of an extensive subterranean network of flooded passages, sinkholes, and caves that host a surprising diversity of fish and zooplankton, most of which are found only in the Yucatán. Many are also endangered, since the peninsula’s cenotes are threatened by development and pollution. One of these species, Antromysis cenotensis, is a tiny crustacean that plays an outsized role in its ecosystem. Included on the Mexican Red List of Species at Risk, the shrimp-like organism makes long vertical migrations as it feeds, thus moving nutrients through the water column. It is also a critically important food source for cenote fish.”