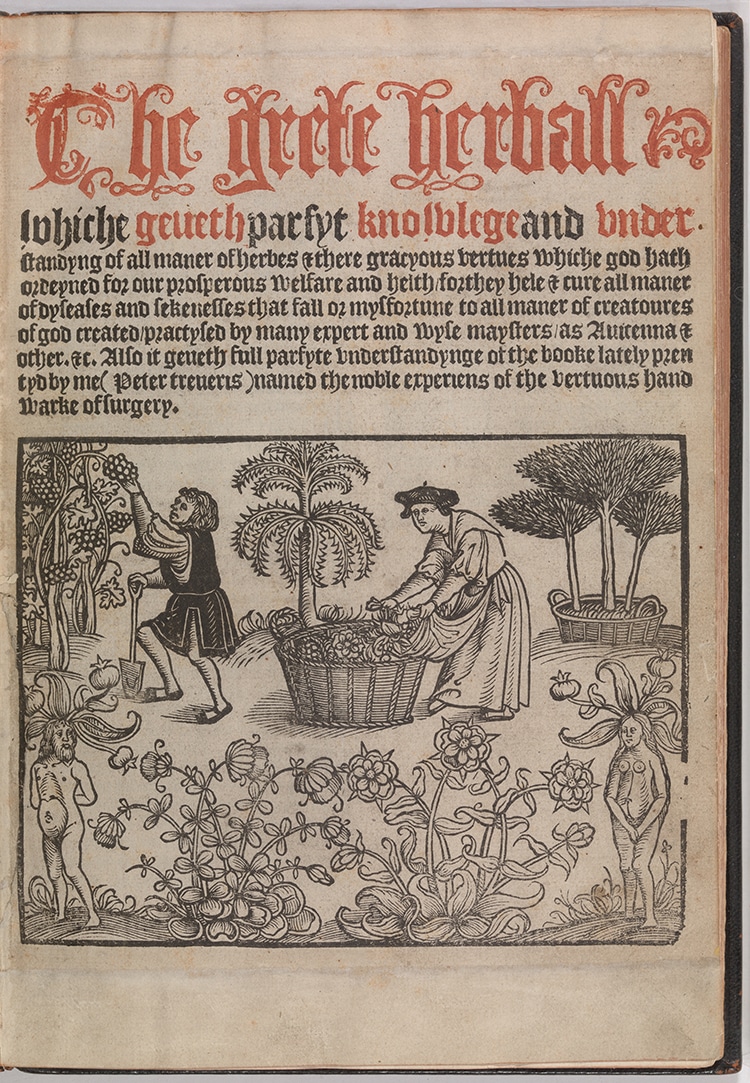

Title page of “The Grete Herball” by Peter Treveris, printed in London in 1526 and illustrated with woodcuts. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

If you were sick in medieval times, how would you be treated? Likely with a “physick,” tonic, or salve. These medicines would often be prepared by local apothecaries, wise women, or savvy housewives. They were based on herbs and other ingredients, some of which may seem quite strange to those used to modern medicine. To cure a headache, you might try a concoction including bishopwort and garlic. Magic or superstitious talismans were thought to aid healing—as could pious prayer.

Critical to the medical knowledge of ancient civilizations, the broad knowledge of herbs was among the antique legacies passed on to Dark Ages Europe. Inscribed in manuscript texts known as herbals, plants and their medical properties became central to the tradition of medieval illuminated manuscripts. Many of the richly illustrated texts have survived to be studied. Whether they record the floral discoveries of the new world or include entries describing mythical mandrakes, the tradition of herbals is a testament to early medicinal thinking as well as the art of the book.

What is an herbal?

An Iris germanica shown in watercolor by Elizabeth Blackwell in “A Curious Herbal,” circa 1737 to 1739. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

At its most basic, an herbal is a written text about plants and their characteristics. Each plant is typically listed with its physical description or an image to aid in identifying safe, poisonous, or benign flora. The medical uses of a plant are often included as well. These could be as simple as helping to cure a headache or as esoteric as encouraging a personality trait such as bravery.

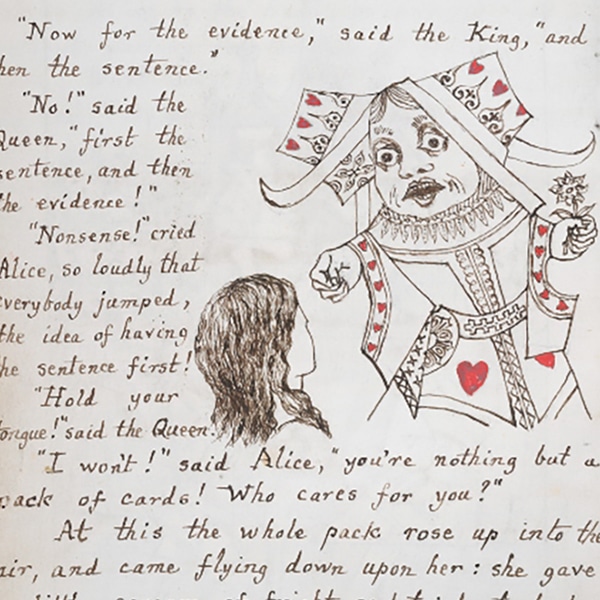

European herbals began in manuscript form and were painstakingly written by hand by professional scribes. These manuscripts could be richly illuminated and illustrated. As the owner of a herbal learned more about remedies and plants, many made notations in the margins or kept pages of their own recipes. This marginalia contributed to a living tradition of text. With the introduction to Europe of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century, herbals—like psalters and prayer books—began to be printed for wider distribution. While printing was new to Europe, the technology was well known in China where woodblock printing was both utilitarian and an art form.

Where and when were herbals made?

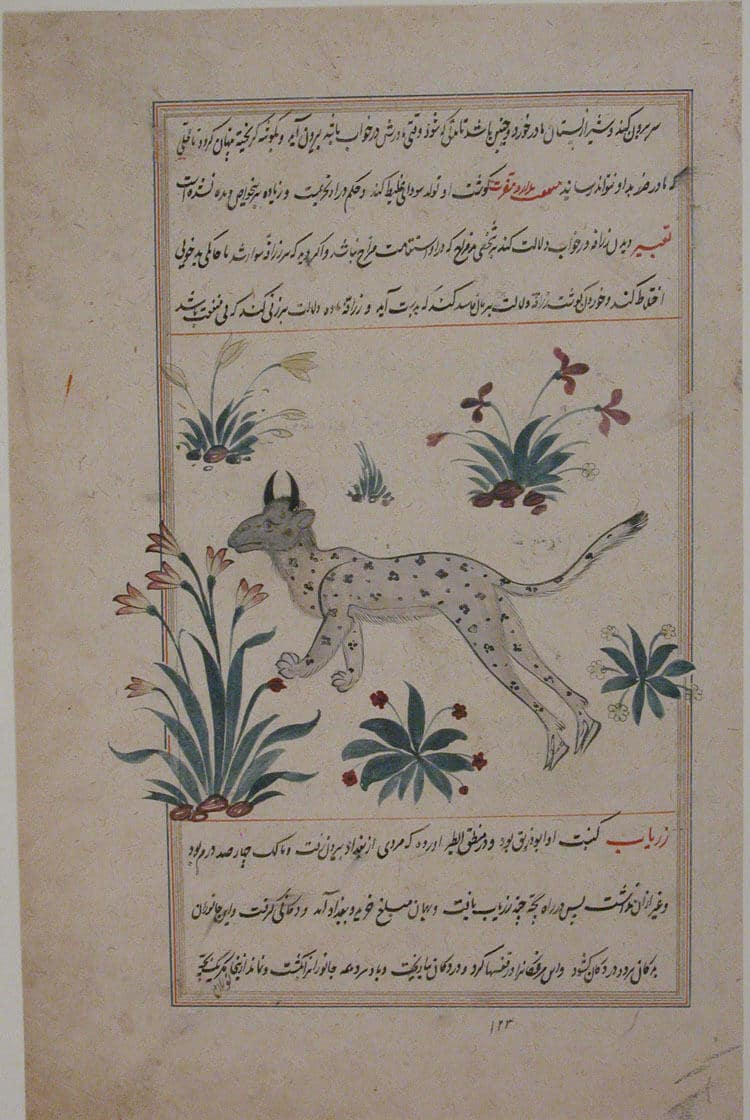

A bestiary and herbal from Iran, circa 1600. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

Herbals are an ancient textual tradition. Medical in nature, these texts often codified knowledge that had long been orally passed on. In Han dynasty China, Shennong Ben Cao Jing (also known as Shennong's Materia Medica) was written down for the first time. However, the 365 plants categorized within it are said to originate in the knowledge and work of the ancient (possibly mythical) ruler and herbalist Shennong. Other ancient compilations of herbal knowledge can be traced in ancient Indian, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian traditions. The Greeks and Romans created some of the most influential herbal texts—although the originals do not survive. Their knowledge was preserved in the medieval manuscripts of the Byzantines, the Islamic lands, and even Dark Age Europe.

The ancients were very interested in medicine as part of natural history. For example, Pliny the Elder wrote Naturalis Historia in the 1st century CE. While often cited as an herbal, the work is in fact a much larger attempt to synthesize knowledge of the natural world. Like other ancient works that survived, it is known through repeated medieval and early modern editions.

In the industrial age, growing herbs for medicinal uses became increasingly less critical to everyday life. Modern pharmacology—while greatly in debt to botanical knowledge—meant that medical textbooks replaced illustrated herbals. However, the herbal text has never vanished into complete disuse. Gardening as a hobby has produced useful guides to diverse flora. Modern herbalists and those who use traditional medicines still turn to the healing properties of plants. While the elaborately illustrated manuscripts of medieval days have morphed into guides filled with photographs, the fascination with the uses of plants remains fundamental.

Explore a few famous examples of herbals from different eras.

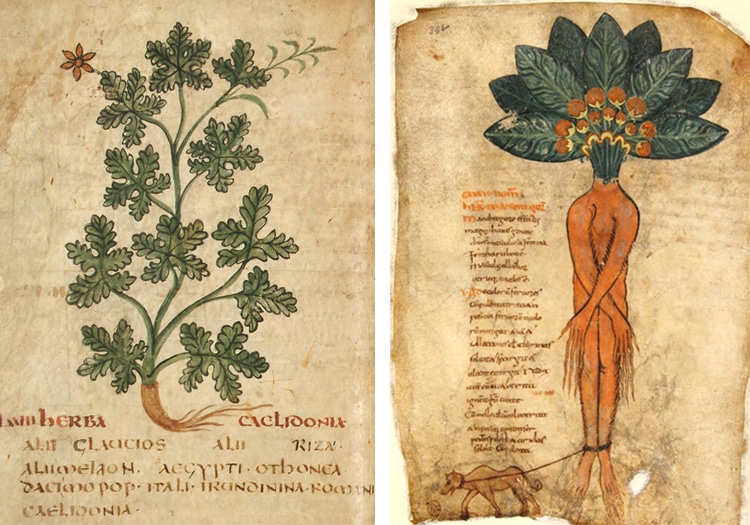

The Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius

Left: The 6th-century Leiden manuscript of the “Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius” (MS. Voss. Q.9.). This page shows Caelidonia. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Right: A mandragora or mandrake in the Kassel manuscript of “Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius,” 9th century. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Among the ancient texts turned medieval lore is the Pseudo-Apuleius Herbarius. The text is thought to be a 4th-century synthesis of Pliny's Historia Naturalis and the Greek Discorides's De Materia Medica. The earliest manuscript dates to the 6th century and is lavishly illustrated. However, countless copies were made of the text through the 14th century and beyond. The work was even translated into Old English, proving the spread of knowledge from Latin to local vernacular. The authorship of this important work remains shrouded in mystery. While originally attributed to the Roman thinker Apuleius of Madaura, this has long been thought to be a copy-cat attribution. Explore this digitized 10th-century version from the British Library or check out this early printed edition from North Africa.

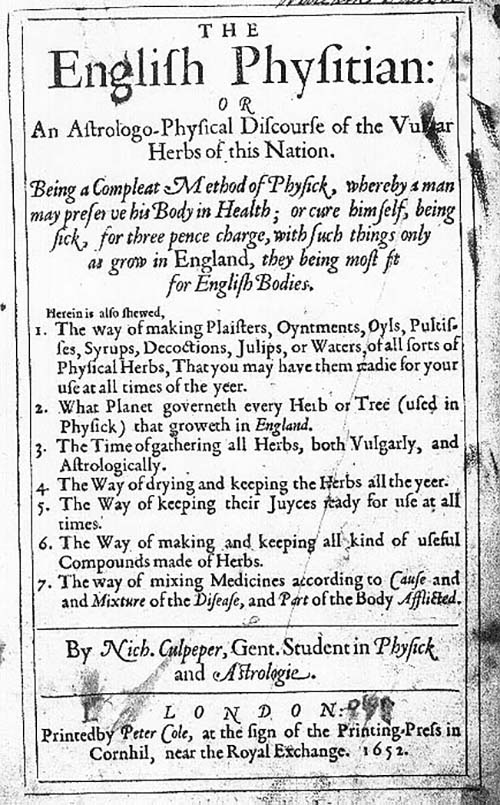

The English Physitian

“The English Physitian” by Nicholas Culpeper, 1652. (Photo: Wikipedia, Public domain)

The 17th century was an important time for medicine and scientific advancement. Nicholas Culpeper‘s work The English Physitian was first published whilst England was mid-throes of the Interregnum—the period between monarchs after the mid-17th century Civil War. The author subscribed to the radical political ideals of the day, but he was also an egalitarian in his approach to herbal remedies; his book detailing simple remedies was printed and sold at a price available to average people.

Based on Galenic humoral theories and the association between astrology and herbs, Culpeper's advice would eventually be known as the Complete Herbal. His herbal would influence the development of medicine across the expanding British Empire. You can read his work online thanks to Project Gutenberg.

The Ebers Papyrus

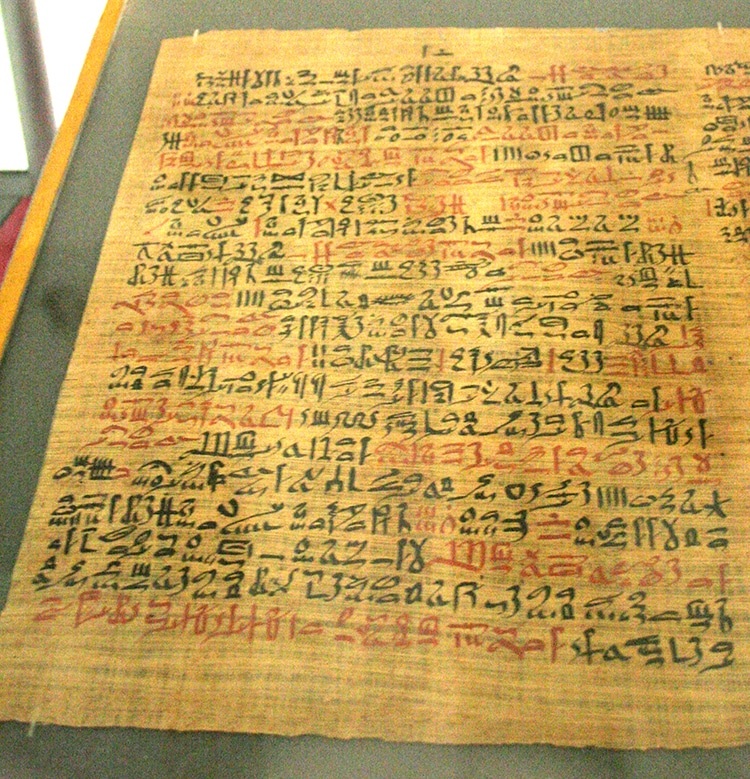

The Ebers Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian herbal and medicinal text dating to the 16th century BCE. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Named for its 19th-century European owner Georg Ebers, the Ebers Papyrus is one of the oldest medical treatises in the world. It is quite extensive; the scroll measures over 20 meters long. Although not fully decoded, its hundreds of useful recipes include many herbal ingredients. While the herbs are not listed as in a classic herbal, the text is an early study in toxicology. Licorice, for example, is used as a laxative while sesame is recommended for asthma.

And many more…

A 17th-century Japanese herbal showing a plant from Peru. (Photo: Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

The above examples of herbals are just a few of the texts to be found in museums around the world. From papyri to printed manuscripts, the herbals of yesteryear have informed the medical developments that save lives today. To explore more herbals, check out this article from the experts at Botanical Arts & Artists. The British Library is also home to many illustrious manuscripts, many of which are able to explore digitally.

Related Articles:

800 Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts from France and Britain Available Online

How Illuminated Manuscripts Were Created During the Middle Ages

World’s Largest Early World Map Stitched Together for the First Time