Photo: Stock Photos from PAVLO S/Shutterstock

A review paper published in Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews has analyzed thirty years' worth of brain studies to conclude that very little difference has ever been successfully shown between the male and female brain. In fact, when ignoring the long acknowledged fact that male brains are typically larger (which does not improve cognition), sex accounts for only one percent of differences observed.

Scientific review papers usually present the state of a research field as it has developed over recent years. Meta-analysis of published studies is a powerful tool. The research team—led by neuroscientist Lise Eliot—analyzed three decades' worth of cadaver and MRI studies which focused on examining the brain for potential differences rooted in sex. The review published by Eliot and her team is a summary of findings made over a very pivotal period in the study of neuroscience. A boom in studies since the 1990s is indicative of vast leaps in brain imaging technology, among other reasons.

While sorting through past studies, the team discovered the field of studying sex differences in the brain has likely been significantly hampered by what is known as the file drawer effect. In scientific fields, many experiments which produce negligible results (i.e. no difference between male and female brains) simply vanish into the files of personal researchers without being published. As a result, published studies skew towards those which “discovered” something, in this case a difference based on sex. In their analysis of the field, the authors demonstrated this bias which has contributed to neurosexism—the persistent belief based on skewed (or even openly biased) science that female brains are less developed, less spatially capable, less logical, etc.

Photo: Stock Photos from YURCHANKA SIARHEI/Shutterstock

Besides pointing out the general bias in the field towards publishing narratives of difference, the authors likewise interrogated the data which has been published to gauge how much difference has actually been discovered. The results are emphatic: the human brain is incredibly similar in structure and function across the sexes. The most notable difference—that adult male brains are about 11% larger on average—has been known since the 19th century. In the 19th century, this was seen as scientific proof of the female brain's inferior capabilities. However, this additional size is mostly attributed to white matter and there is no correlation that bigger brains are “better” for cognition. The male brain being larger produces the same effects as one female brain being larger than another of the same sex.

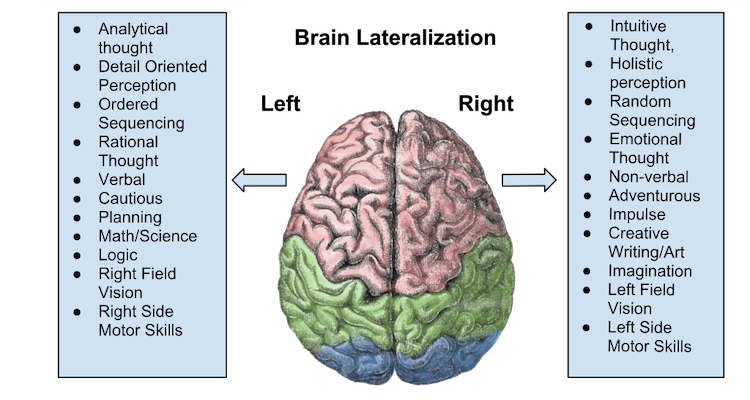

When isolating and removing brain size as a difference, the team discovered the published findings of the past 30 years do not support the idea that human brains are dimorphic—meaning occurring in two distinct forms. In fact, they appear to be quite monomorphic. For differences in brain structure and laterality (dominance of one side of the brain), sex appears to statistically account for less than one percent of difference. This finding completely debunks ideas that men are more left-brained (logical, reasonable) and women are more right-brained (emotional, artistic). This myth dates to the 19th century, when the hemispheres of the brain were even explicitly identified with the sexes.

Photo: Chickensaresocute (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Rather than male and female brain structures, this recent review of the field suggests a new direction for studying the human brain as monomorphic. Neuroscientists are beginning to reframe the way they approach the brain and sex difference. As science and society continue to explore the nuance of both gender and sex, the differences of human brains are being explored in new ways. A 2015 paper found that the brain is in fact a “mosaic” of characteristics, some of which appear more commonly in males or females. That paper, too, found that “human brains cannot be categorized into two distinct classes: male brain/female brain.” While sex and gender are associated with certain behaviors and even psychiatric disorders based in brain chemistry, Eliot et al.'s review describes these matters as much more complex than a simple dichotomy of brains based on sex.

The review paper by Eliot et al. is a new phase in the nature versus nurture debate with regards to the brain. It detangles certain confusing threads. For example, there is no evidence that female brains are innately less capable of advanced logical thinking than male brains. However, in society, it has been observed that socialization often teaches young girls that they should not be good at math, resulting in less women in STEM. However, in Cold War East Germany, the radical social structures which emphasized greater gender parity than in West Germany were shown to correlate with better math scores and confidence among girls. In short, the brain and human behavior are highly variable and influenced by cultural expectations, socialization, and even factors such as epigenetics. As the authors of the review note, “lifelong neuroplasticity” (the adaptability of our brains) means these factors must all be considered by neuroscientists.

While the scientific details are hashed out in labs and scholarly journals, the neurosexism debunked by this review paper is still pervasive in popular culture. With the popular release of The Queen's Gambit in 2020, attention focused on the sparse numbers of female chess players, particularly at the highest levels of competition. Many male chess players have spoken on this over the decades, frequently attributing it to differences in female brains (as well as other outdated notions about gender roles). To debunk this instance of popular neurosexism, Wei Ji Ma—a professor of neuroscience at NYU who is also a chess master–wrote a piece for Slate on why there is no evidence showing brain “hardwiring” has anything to do with women in chess. While it is easy for popular culture to play on notions of sexual difference in human brains, it is best for all of us to follow the science and leave neurosexism behind.

h/t: [IFL Science]

Related Articles:

Revolutionary Funeral Facility To Turn Humans Into Compost Is Now Open

Scientists Discover That Your Brain Stays Half Awake When You Sleep in a New Place

Enjoying Wine and Cheese Might Actually Help You Avoid Dementia Later in Life