Gustave Moreau, “The Apparition” (detail), ca. 1886 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

In 1886, Greek writer and art critic Jean Moréas published a manifesto on Symbolism. Described by Moréas as a “present thrust of the creative spirit in art,” Symbolism was sparked by an interest in spirituality, materializing as a movement that favored subjectivity over realism.

While Symbolism's popularity waned in the early 20th century, its influence has been long-lasting, touching subsequent movements and inspiring artists for years to come. Here, we take a closer look at this dreamy genre, exploring everything from its fascinating origin to its enchanting legacy.

What is Symbolism?

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, “The Dream,” 1883 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Taking this approach to the next level, Symbolists strategically produced works whose contents (whether written or painted) served as symbols of deeper ideas—not as a means to replicate reality. “Every manifestation of art meets with fatal impoverishment and exhaustion,” Moréas wrote in Le Symbolisme, his Symbolist manifesto, “then follow copies of copies, imitations of imitations; what was new and spontaneous becomes cliché and commonplace.” Channeling dreams and harnessing the subconscious, he believed, would revive the arts and breathe new life into a cultural landscape lacking imagination.

The Symbolist Movement

Writing

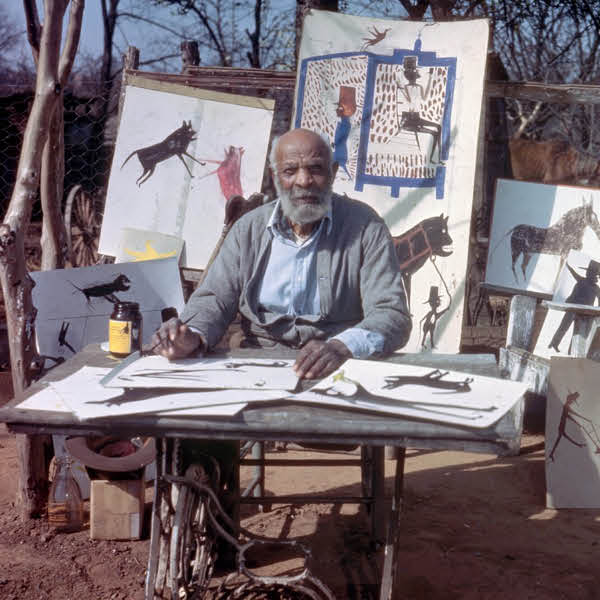

Frédéric-Auguste Cazals, “7e Exposition du Salon des Cent” (detail featuring Paul Verlaine and Jean Moréas), 1894 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

On top of Symbolism's more abstract qualities, the manifesto also outlined its technical considerations. According to Moréas, Symbolist poetry comprises “falling undulations,” “mysterious ellipses,” “rhyme of abstruse fluidity,” and other writing tools favored by poets interested in “freely firing the fierce darts of language.” These Symbolist elements are particularly evident in the prose-poetry of Charles Baudelaire, the complex works of Stéphane Mallarmé, and Paul Verlaine‘s “poetic art.”

In addition to poetry, Symbolist writers also wrote prose, which they published in periodicals, like Le Figaro, and literary magazines, including Le Plume.

Fine Art

Gustav Klimt, “Judith I,” 1901 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, for example, favored dreamy subjects rooted in mythological tales and biblical stories; Gustav Klimt preferred painting ethereal portraits of women and surreal allegories; Edvard Munch excelled in dark and dreary paintings and prints; and Odilon Redon explored everything from floating floral studies to anthropomorphic spiders rendered in what he believed to be the most spiritual hue: black.

“Black is the most essential color,” Redon said. “It conveys the very vitality of a being, his energy, his mind, something of his soul, the reflection of his sensitivity. One must respect black. Nothing prostitutes it. It does not please the eye and it awakens no sensuality. It is the agent of the mind far more than the most beautiful color of the palette or prism.”

Influence

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for “The Slav Epic” exhibition, 1928 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Subsequent writers looked to Symbolist poets for inspiration for decades. Specifically, as writer Wallace Fowley has noted, “ever since the rich period of Symbolism . . . French poetry has been obsessed with the idea of purity“—a concept pioneered by Symbolist poets. It is not just fellow writers, however, who have turned to their work. Composers have also cited specific Symbolist poems as their muses, with Claude Debussy's Clair de lune (a piece based on a poem by Paul Verlaine) serving as a particularly celebrated example.

Modernist artists were also drawn to Symbolism. Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha, a contemporary figure, adapted the movement's use of metaphor and dreamy imagery to craft spellbinding and sinuous paintings and prints. Les Nabis, a color-loving, cult-like group of Post Impressionists, also incorporated meaningful symbols into their paintings, while the Surrealists, channeling the Symbolists' focus on the imagination, famously relied on the subconscious as a source of creativity.

“The imaginary,” Surrealist pioneer André Breton said, “is what tends to become real.”

Related Articles:

How “La Belle Époque” Transformed Paris Into the City We Know and Love Today

Moulin Rouge: Explore the Dazzling History of Paris’ Most Celebrated Cabaret

8 Iconic Artists and the Inspiration Behind Their Favorite Subjects

5 Facts About Edgar Allan Poe – the Literary Master of the Macabre