Mary Cassatt, “Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge,” 1879 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

When you think of Paris, its illustrious landmarks likely come to mind. While some of these monuments date all the way back to the Middle Ages, many of them were constructed during La Belle Époque.

Emerging in the late 19th century, this “golden age” saw the construction of icons ranging from the emblematic Eiffel Tower to the city's sinuous metro entrances. Architecture wasn't the only art form transformed by La Belle Époque's golden touch, however; French art and literature also made major strides during this period, culminating in a cultural phenomenon unlike any other.

What is La Belle Époque?

Stock Photos from Everett Historical/Shutterstock

Literally translated to “the beautiful era,” Paris' La Belle Époque lasted from 1871 to 1914. During this time, several aspects of Parisian culture saw important developments. In fine art, Impressionist, Cubist, and Fauvist pioneers revolutionized painting, and graphic designers elevated printmaking to a fine art form. Architects executed plans for a new Paris, while writers made their mark with a more modern approach to storytelling.

What sparked such an all-encompassing golden age? To find out, one must contextualize this cultural event within history.

Historical Context

English: The rue de Rivoli after the fights and the fires of the Paris Commune, Paris 4th arr. In the background, the hôtel de ville de Paris, 1871 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In the summer of 1871, the City of Light was finding its footing after the fall of the Paris Commune. The Paris Commune was a revolutionary government that emerged as a result of France's defeat during the Franco-Prussian War and, consequently, the collapse of Napoleon III's Second Empire. Backed by the National Guard, this radical left-wing commune seized power on March 18 and ruled Paris until May 28, when the city was reclaimed by the French Army—but not without a fight.

During the violent confrontation, buildings across Paris—including Haussmann apartments on the bustling rue de Rivoli, Hôtel de Ville, Paris' city hall, and most symbolically, the Tuileries Palace—were set alight. As a result, the new government was faced with the task of rebuilding Paris. While some buildings were restored to their original selves, others were either rebuilt in a new style or replaced entirely. In any case, these projects ushered in a new period of Paris: La Belle Époque.

Cultural Contributions

Iconic Architecture

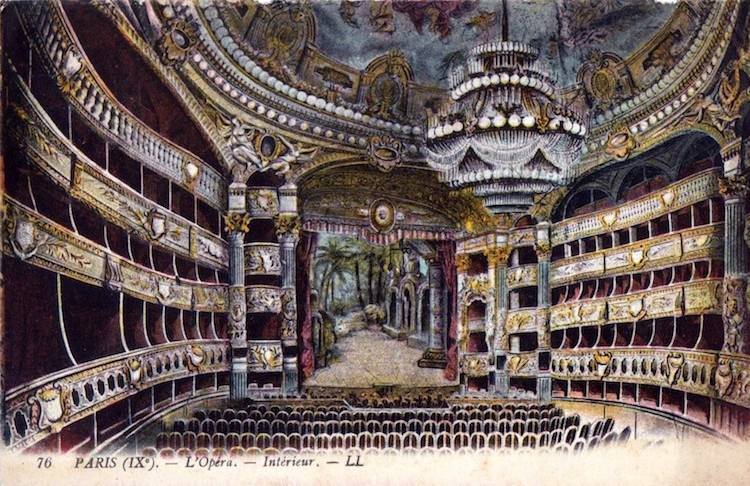

Palais Garnier's interior, postcard from 1909.(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Paris' architectural developments during La Belle Époque cannot be understated. In addition to the Eiffel Tower—a “great pylon” designed to serve as an entrance to the Exposition Universelle, or World’s Fair, in 1889—the period saw the construction of Beaux-Arts buildings like the Gare d'Orsay (the present-day Musée d'Orsay), the Petit Palais, the Grand Palais, and the Palais Garnier, Paris' premier opera house. The dazzling domes of Grands Magasins, or department stores, changed the skyline; Art Nouveau entryways transformed the underground; and the Romano-Byzantine Sacré-Coeur breathed new life into the heart of Paris.

Avant-Garde Art

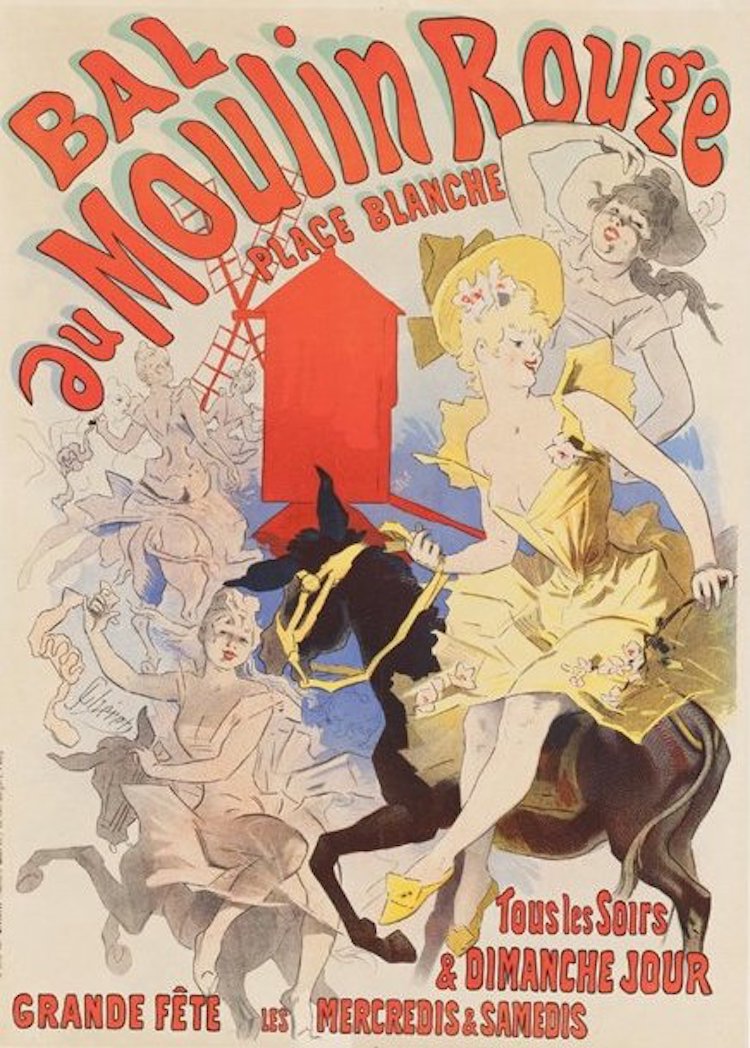

Jules Chéret, “Bal du Moulin Rouge,” 1889 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In fin de siècle (“end of century”) Paris, art underwent an avant-garde overhaul. Until the 1870s, most French painters clung to the traditional tastes of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. This prestigious Parisian organization held annual salons that exhibited a carefully selected collection of art. Typically, the jury favored works featuring conventional subject matter, from historic portraits to religious allegories. Reacting against these stifling standards, a group of artists—including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro—began working in a style characterized by unrealistic brushwork and ordinary subject matter. They held independent exhibitions, and eventually came to be known as the Impressionists.

The Impressionists paved the way for other modernist movements, including color-crazy Fauvism, abstract-minded Cubism, and eclectic Post-Impressionism. In addition to painting, however, La Belle Époque saw major strides in graphic design, when Jules Chéret, the “father of the modern poster,” introduced the color lithograph. With this new technology, artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha boldly immortalized the cafes, cabarets, and clubs that colored turn-of-the-century Paris.

Notable Writers

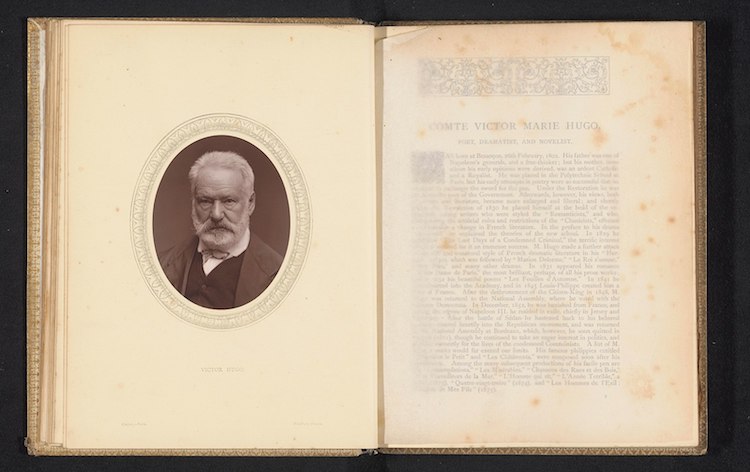

Portrait of Victor Hugo (ca. 1871) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

During La Belle Époque, Paris became a writers' hub. Among its most influential figures were short story pioneer Guy de Maupassant and Naturalist novelist, playwright, and journalist Émile Zola. Even Romantic writer Victor Hugo—who was raised in Paris but lived in exile from 1851—returned to the French capital in 1871 at the age of 68.

While he wrote his most famous Paris-set works years earlier (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and Les Misérables in 1831 and 1862, respectively), his lifelong work and love of Paris undoubtedly inspired writers to flee to the capital during La Belle Époque.

The End of an Era

Stock Photos from Premier Photo/Shutterstock

Just as military conflict sparked Paris' Golden Age, it also extinguished it. The onset of World War I brought an abrupt end to the period of prosperity, as Paris' recent cultural developments were overshadowed by mobilization efforts. In fact, it was during the war that La Belle Époque retroactively received its romantic name.

Though the era has long since ended, its presence can still be seen and felt throughout the City of Light, illustrating the range of its influence—and Paris' unchanging legacy. “He who contemplates the depths of Paris is seized with vertigo,” Victor Hugo wrote. “Nothing is more fantastic. Nothing is more tragic. Nothing is more sublime.”

Related Articles:

5 Must-See Museums in Paris (That Aren’t The Louvre or Musée d’Orsay)

5 Rock-Solid Facts About Paris’ Amazing Arc de Triomphe

6 Places in Paris Where You Can Still Experience Notre-Dame’s Medieval Magic