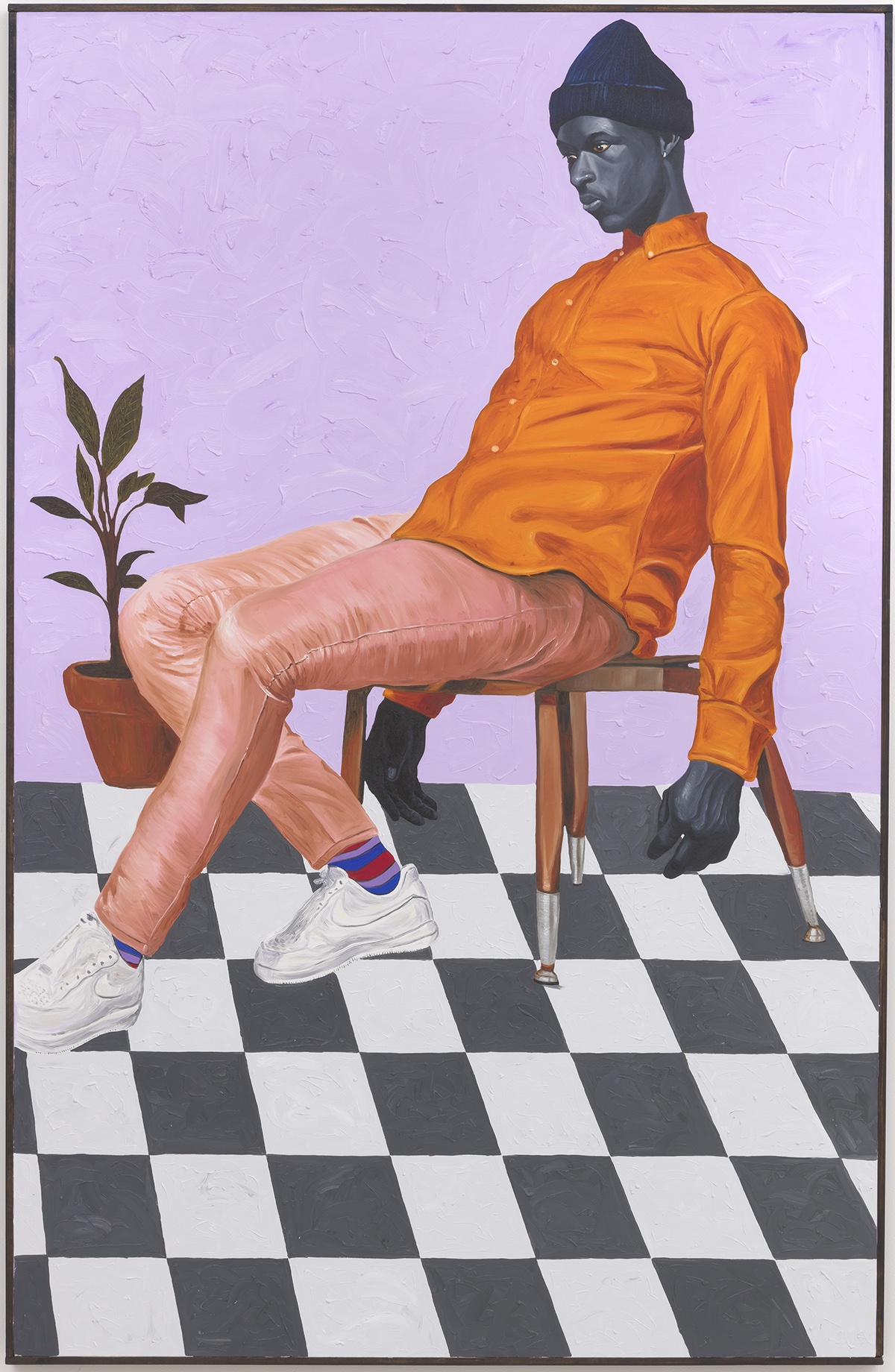

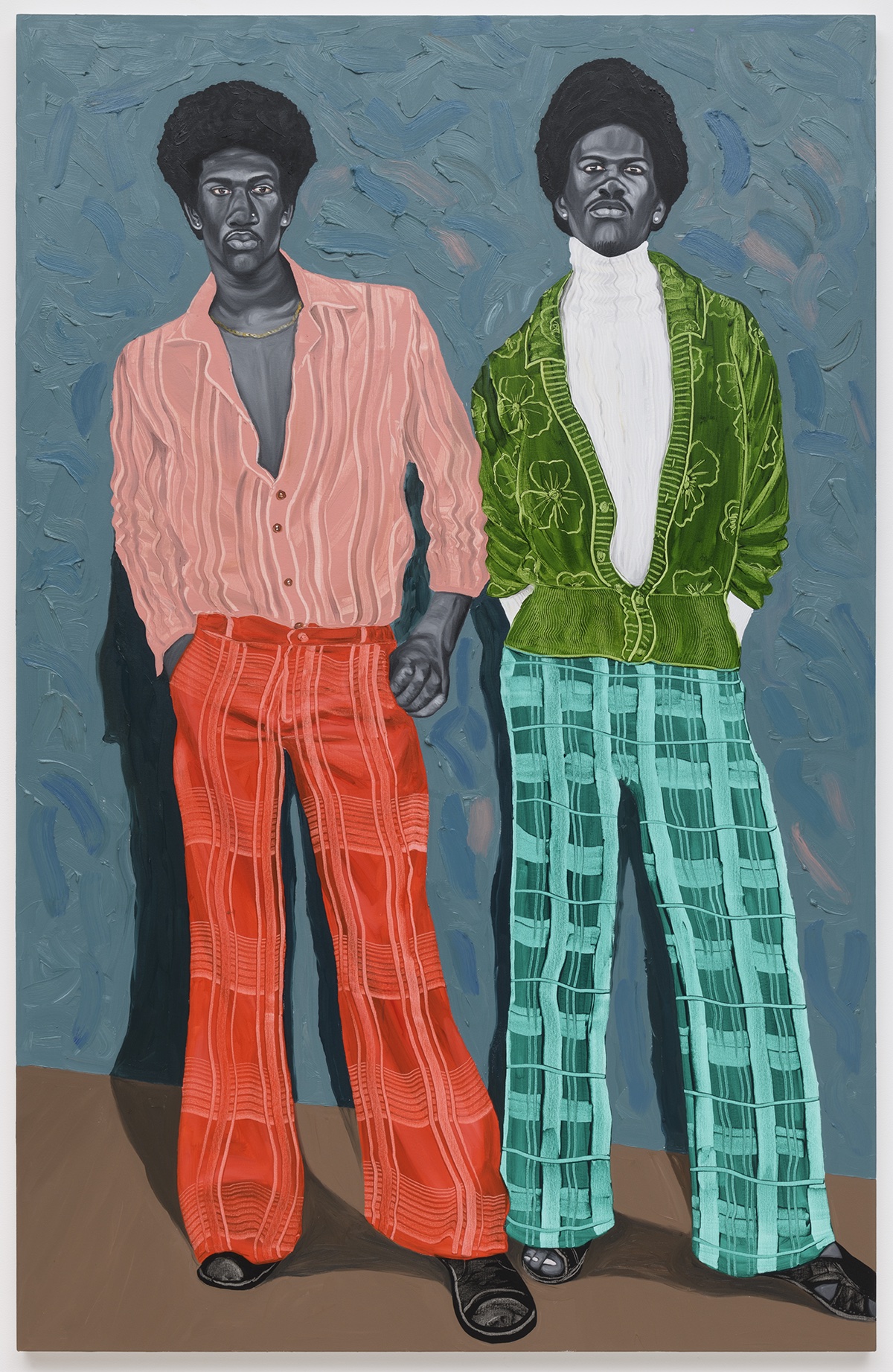

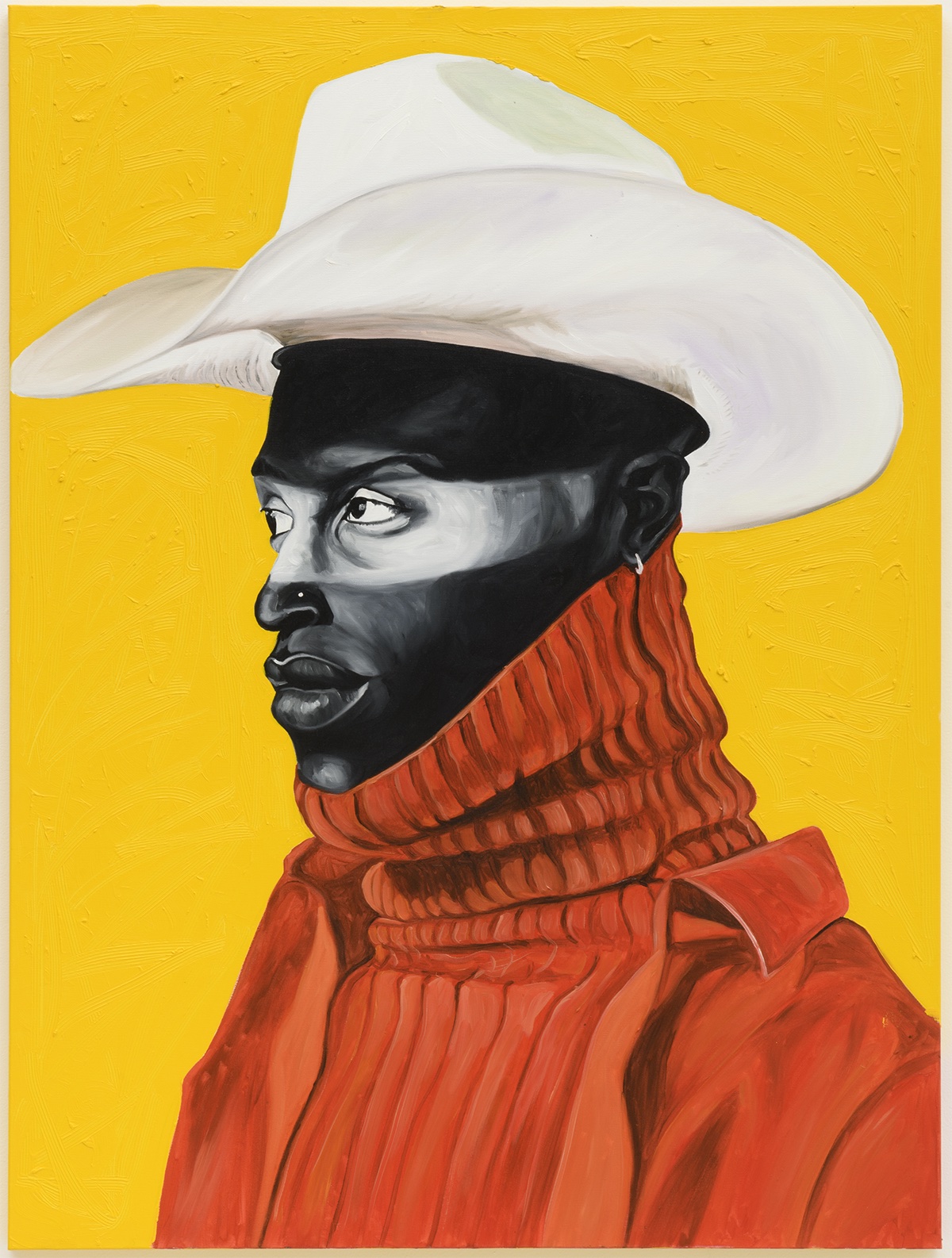

“Sitter,” 2019

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Robert Wedemeyer)

While bathing his viewer in a world awash with vibrant color, Ghanaian artist Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe forces them to look and truly see the figure staring back at them from the canvas. His evocative portraits explore what it means to be Black in America—whether you’re from here or not. And it’s impossible not to be drawn in by the arresting intensity of each subject’s gaze and their cool, collected demeanor. Behind each person is a life and a story.

As an immigrant to the United States, he’s had his fair share of experiences with the stereotypes, injustices, and nuances that come simply as a result of the color of his skin. Using his art, he seeks to give a voice to those who experience the same struggle and forge a bond of solidarity between them. Even delving into the forgotten history of the Black Cowboy—”one in four American cowboys was Black, yet the enduring narrative of the cowboy figure is that of the heroic white male”—his artworks tell a story that is both personal and universal.

We had the chance to chat with Quaicoe and learn more about his journey as an artist and the meaning behind his work. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

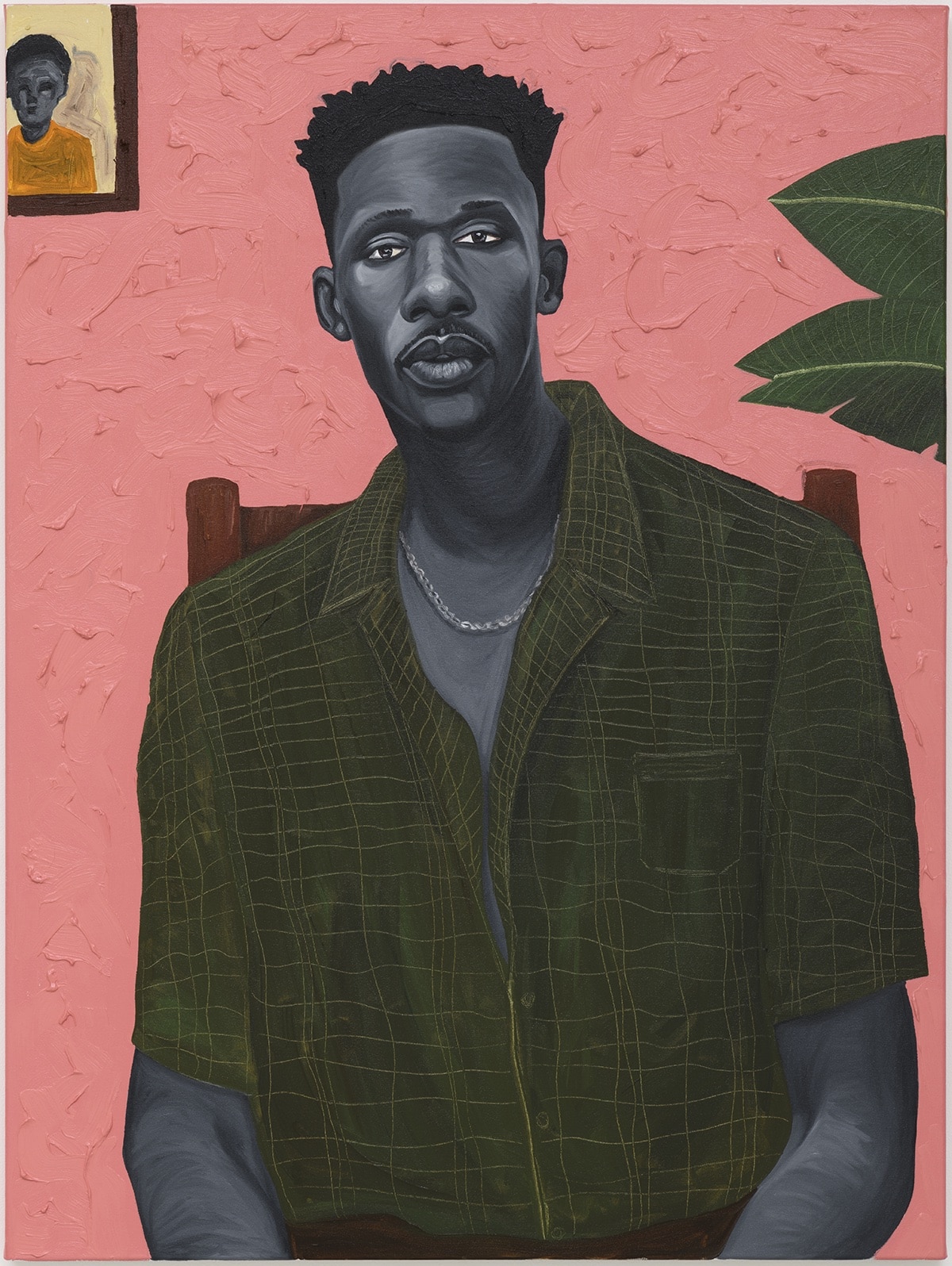

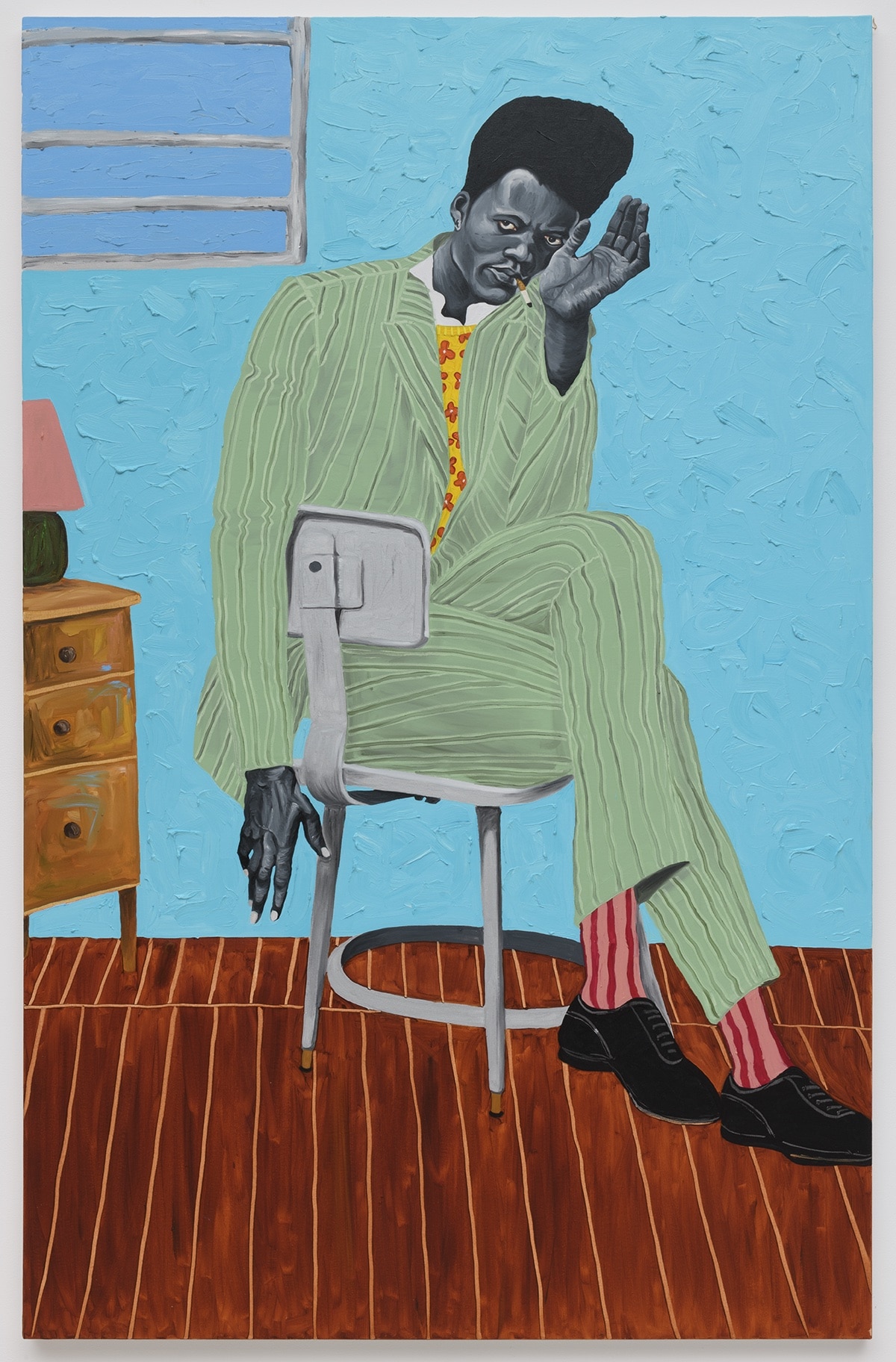

“Observing,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

How did you get started in painting?

Well, the reason I started painting was out of curiosity. I've always been a curious person since I was a child, and I watched movies all the time because I love movies. I just love the story behind movies—how people are able to take a story and make it into something visual like that—and there was this one movie theater that I used to go to all the time.

One day when the movie was over, I came out of the theater, and there was a door that was cracked open just a little bit. So, being curious, I peeped inside to see what was behind that door, and I saw a bunch of artists working on huge posters. Then, I realized that those posters were the same ones hanging in front of the movie theater. The posters that I’d been seeing were actually hand-painted by these artists that were commissioned to do that.

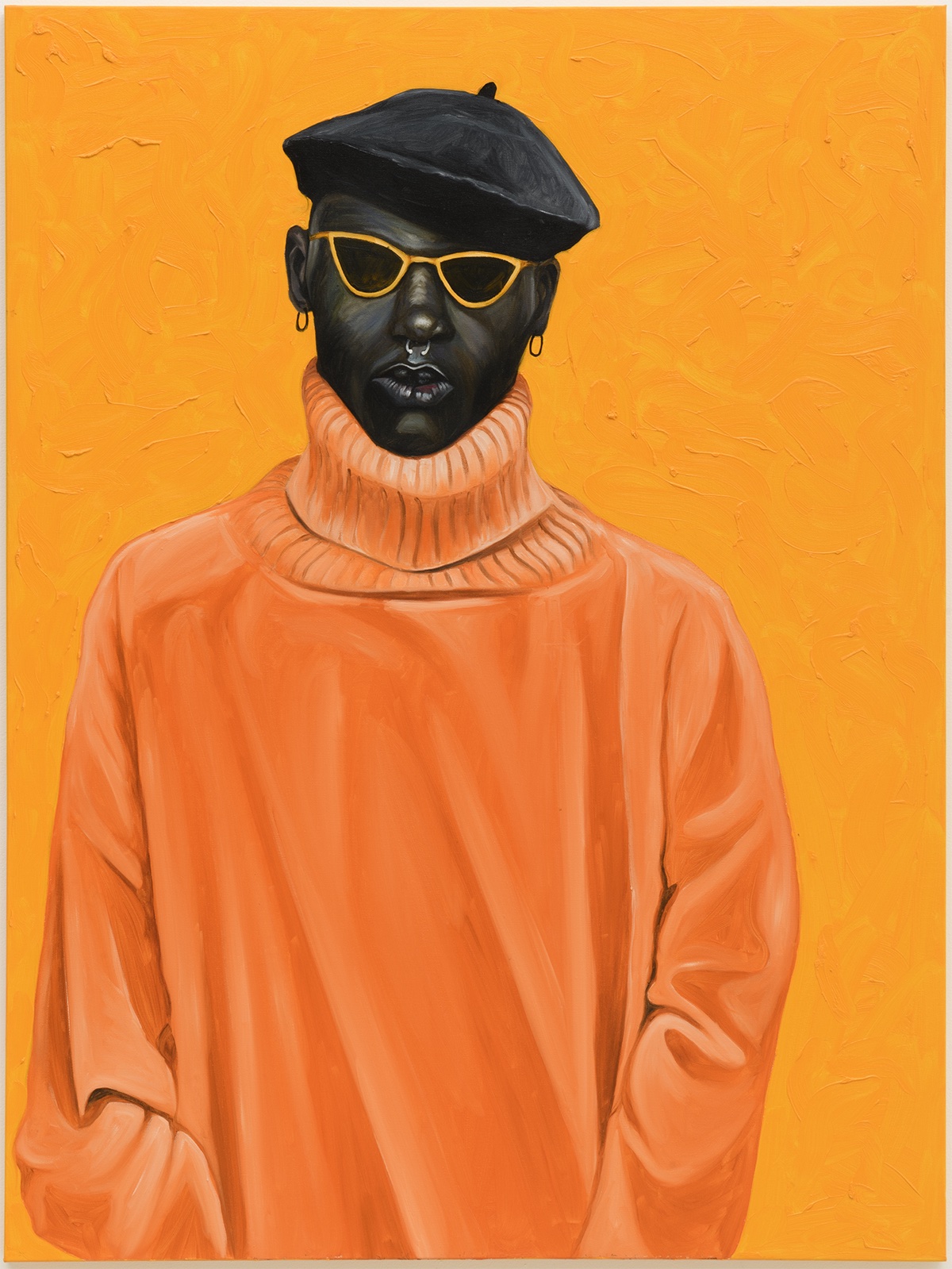

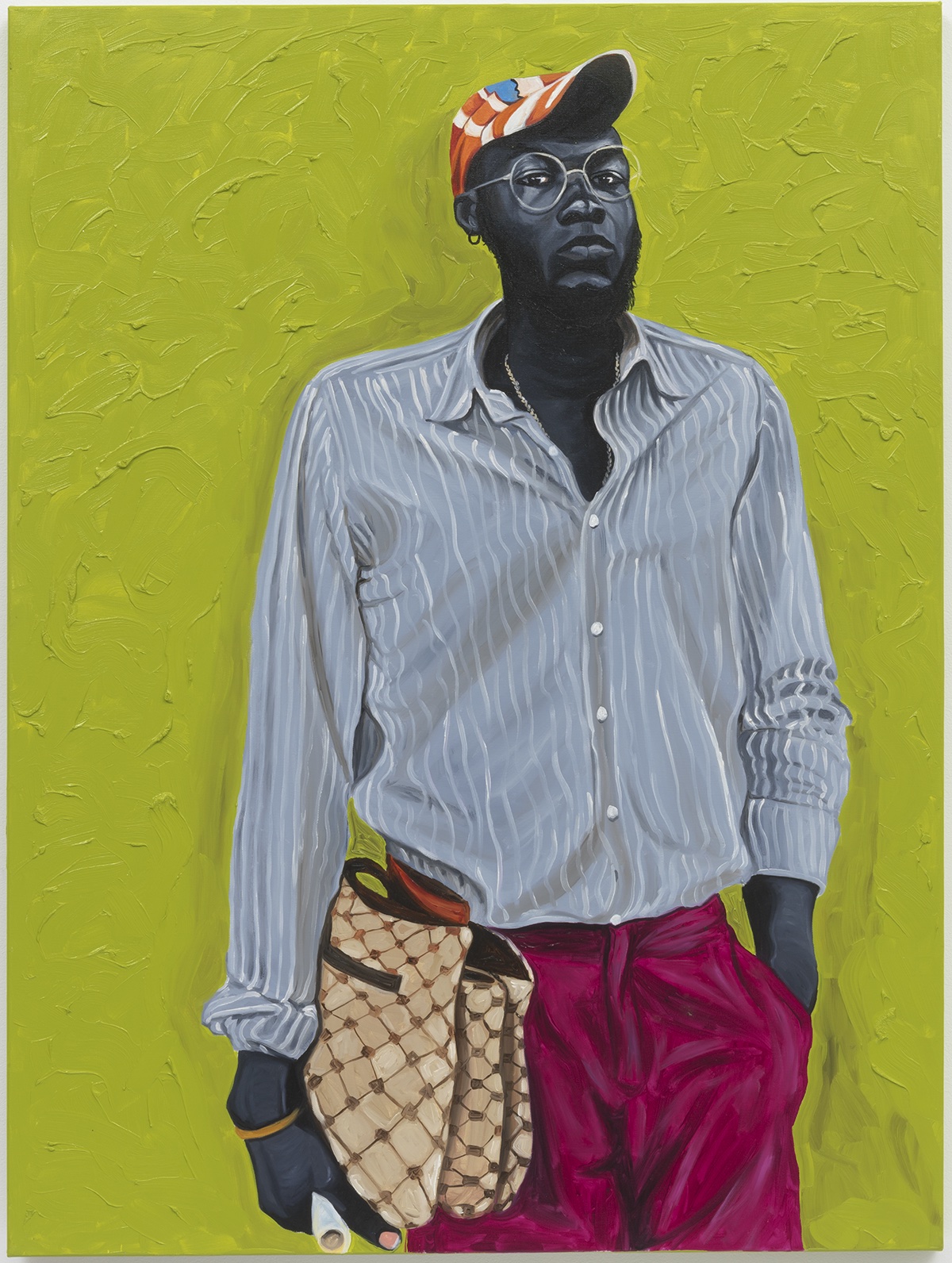

“Dapper II,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

(continued) That just blew my mind—how they were able to recreate a scene from the movie, capture that part of it, and then just paint it? For me, it was just something out of this world. I wished I could do that. That is how I've always been; it's just part of me. I always liked to challenge myself and see if I could do something. So, I reached out to one of the artists and told them that I would like to do that as well, and they were willing to teach me, bit by baby bit. And after that, I started to recreate anything that I could get my hands on—pictures from magazines, newspaper prints, photographs, or anything. I just started to recreate the same thing over and over and over.

So, gradually it became something I realized that I really loved. But I didn't know you could actually make a living or become somebody just painting. It was just something that I loved to do when I was growing up. Years later, someone introduced me to an art school. There, for the first time, I knew this was what I really wanted to do. So, I practiced art there for four years at the Ghanatta College of Arts and Design.

“Daniel Caesar,” 2019

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Robert Wedemeyer)

What led you to portraiture in particular?

When I came out of school, I started diving into other aspects of art as well. I love photography—especially the old photos in black and white—so I practiced that a little bit. A friend, who is a professional photographer, taught me how to shoot photographs and all that. And that is actually where portraiture started for me because, in school, I was mostly interested in abstract art and landscapes. This was mainly because I felt abstract gave me the free will to express myself in a way without judgment or me having to explain myself so much.

Sometimes it's just what you feel that you paint, when it comes to abstract. Sometimes there are certain things that come to you that are unexplainable, so you express the visual elements. But, after learning photography, I felt more connection with people. I thought that this was something that, when you paint, you can have some sort of emotional connection with. I felt more free with that, so I decided to practice more and become perfect in that—trying to capture the emotions and the same energy from a photograph. That is how portraiture and figuration started for me.

“Orange Turtleneck,” 2019

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

Do you base most of your portraits off of photographs now, or do you prefer in-person sittings?

I base them mostly on photographs. The reason why I love using photographs is that, when you bring a person in to sit for you, I feel you lose the essence of the person. Because when a person sits for you, and they sit for a long time, they tend to get tired. Then you start to lose their image and the good vibe you got from them from the beginning.

When they come in for the first time and you tell them to sit and feel free and be themselves, then you take the photograph, you just capture a moment that you only get once. And with photos, their focus is more directly looking at you, and you get all that kind of a real emotion that you want. That is also why I like taking the photographs myself.

Of course, I don't do any kind of editing to the photos. The only thing I do is change the image to black and white so that I get the real light source, where my light is coming in. I feel when the picture is in color, you can get all sorts of distractions. In black and white, it gives me the proper lights, all clean, and all the tools that I need.

“Isolation,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

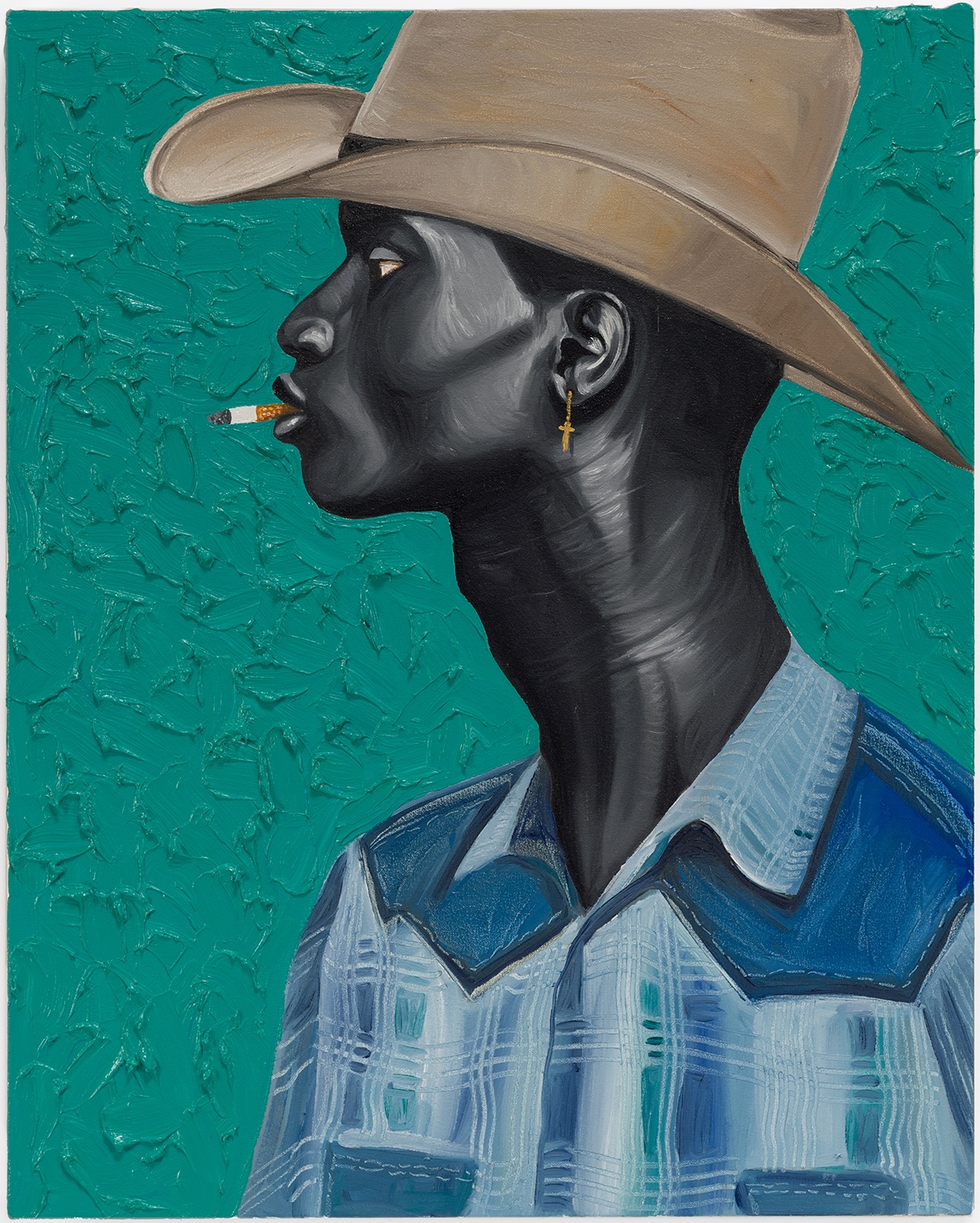

One striking component of your work is your use of very vibrant and vivid color. Since you’re usually working from a black and white photograph, how do you go about choosing your color palettes? What is the significance of color for you?

I love colors, especially bright colors in general. Personally, it's a way of me expressing myself. That is how I like to show who I am as a person. And I believe it's the same with everybody. People dress in a certain way just to let others know who they are and feel good because that is who they are. And there are certain colors that bring their character and their vibes out.

Where I grew up, and where I live in Ghana, color means a lot to us because color is associated with the tribes. And when I say tribes, it’s just like how you have states in the U.S. We have regions, and every region has tribes in them. And there are certain things that we use or wear that will tell you which tribe we belong to. The same thing happens with colors as well. There are certain colors that you can identify, and it’s a means and a way of identity. So, I try to involve that when I'm working on my canvas.

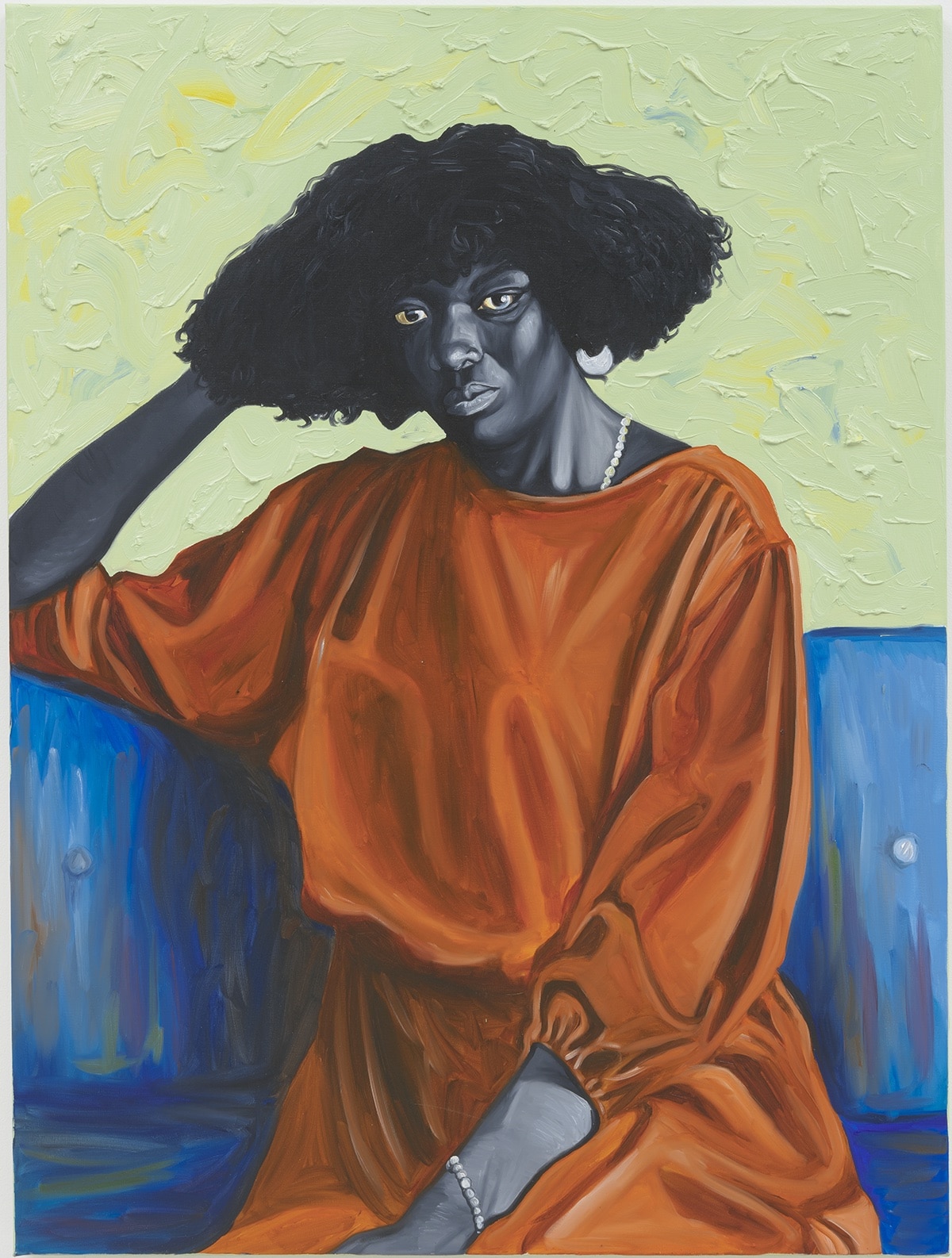

“Lady on Blue Couch,” 2019

(Sourced from an image of Velma Rosai Makhandia, originally photographed and copyrighted by Naafia Naahemaa, Berlin, 2018); Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of John Auerbach and Ed Tang, © Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, image of painting by Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles.

(continued) Much of it is personal. But when I am working on something that expresses that, I also try to base it on the person—my subject. Because, whoever I am painting, I'm also putting that person out there—the person's character, who the person is, what the person loves. I mostly feed on the energy of the person, and I associate that with a certain color, which is always based on the person's character. That is how I choose my colors because it's also a way of communicating with people.

“Daniel Quist,” 2019

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Robert Wedemeyer)

In the midst of all those bright colors on your canvases, you usually leave the subject themselves in grayscale tones. What is the reasoning behind that?

Some of the reason is to appreciate the skin tone of Blackness—the beauty of Blackness—and to appreciate and accept who we are. Yeah, of course, we are not all that same shade of black as in the painting, but it's a form of representation of who we are and how Blackness is being portrayed in the media and all the stereotypes. So, it's also a way of putting it out there to empower ourselves and to say that, “Yeah, this is who we are, and you better accept it or leave it.”

It's just a reference to how we live, especially in the States; but I know this happens everywhere else as well. We live in a beautiful, colorful world—colorful States—but black is always identified among all those beautiful things. So that is something that I try to portray. With all the beautiful colors of the background, you still see this figure sitting right in the middle of it.

“Dapper,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

(continued) That's exactly what I try to portray because it's just like being in the spotlight. There are a lot of people, but you are always being identified. You are always, sort of, the target. That is why I put so much tension in the eyes. I always like the subject to stare at you or to stare into space and make you wonder who the person is.

It's also because I have had my experience here with racial injustice and all that as well. So, I always channel what I have been through and what others have been through, and then I just try to put something together and put it out there. Because, even though I always say I'm an African, it’s different once I get here in the United States. You are no longer African; you are a Black person. That's it.

“Joseph Cubo,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

Has your experience here in America been something that has had a great influence on your work since leaving Ghana?

Yeah, it has been a big influence—a really, really big influence. Because back when I was in Ghana, my subjects were more based on politics most of the time—poor kids on the streets, environmental stuff. But when I got here, I had a different approach because of what I was also going through. Because I also suffered the same injustices that the African American suffers here. So, what better way to talk about that than using my art?

As I said, when you get here, all people see is your skin tone. Nothing else. You are being approached the same way they would approach any other Black person who lives in the States. So it became something that I wanted to talk about. But how best can I do that, except paint, and then use that as my voice? So I started meeting other people in town—other Black folks—and then just having conversations about how they live and how they're being treated. What they go through in their normal, busy daily life. So it's a huge part of the influence that has gotten me painting in this way—the struggle, and my experience as a Black person and as an immigrant living in the States.

“Side profile of David Theodore,” 2019

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California; (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

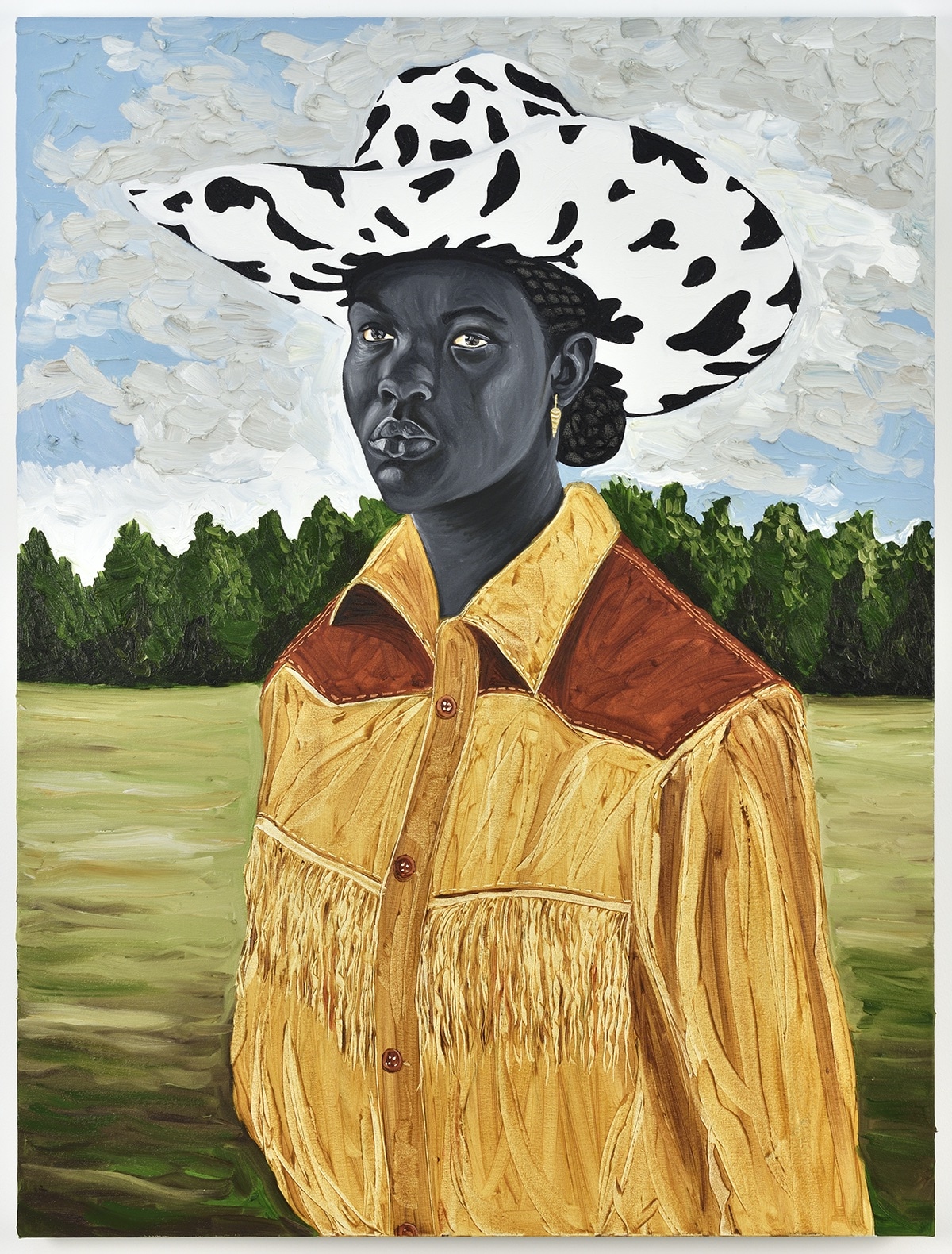

You are also working on a series of artworks centered around the “Black Cowboy.” Can you tell us a little bit more about that and what the inspiration was behind it?

It takes me back to when I used to watch movies. Cowboy movies were some of my favorites that I used to watch all the time, and I used to play and pretend to be one of the characters when we were done watching the movie. I would see myself as a cowboy hero kind of thing; but, sitting back, I realized there weren’t any Black people or anyone who looked like me as a cowboy in the movie.

So it all started as imagination for me. If there was a Black cowboy, well, how would he look? Would he look different from the white cowboy? I formed my own idea of how a Black cowboy would look and how he'd dress, and I would always try to infuse that with our modern way of dressing. It's like, if there were a Black cowboy, they would be a cowboy with swag and all that. It was just an imaginary thing that I would play with—we’ll have the normal, traditional cowboy hat with the nice, long sleeves and all that, but we'll have cool Nikes on, or Adidas, or something like that.

“Sheena Skipper Blue Demin Jacket (cowgirl),” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Robert Wedemeyer)

(continued) That is how it all started for me until I put it into visual. When I got to the States—when I found out about the Compton Cowboys—that opened up a huge door, and I was like, “Whoa, they actually exist!” So I started researching more and more, and then I found out all this stuff about cowboys. It goes on and on and on.

It’s just crazy, all the real information and real truth that has been hidden from us for so long. So it’s good that I got to find out. And I always say that this pandemic and all the protesting brought out a lot of information, and that’s a really good thing.

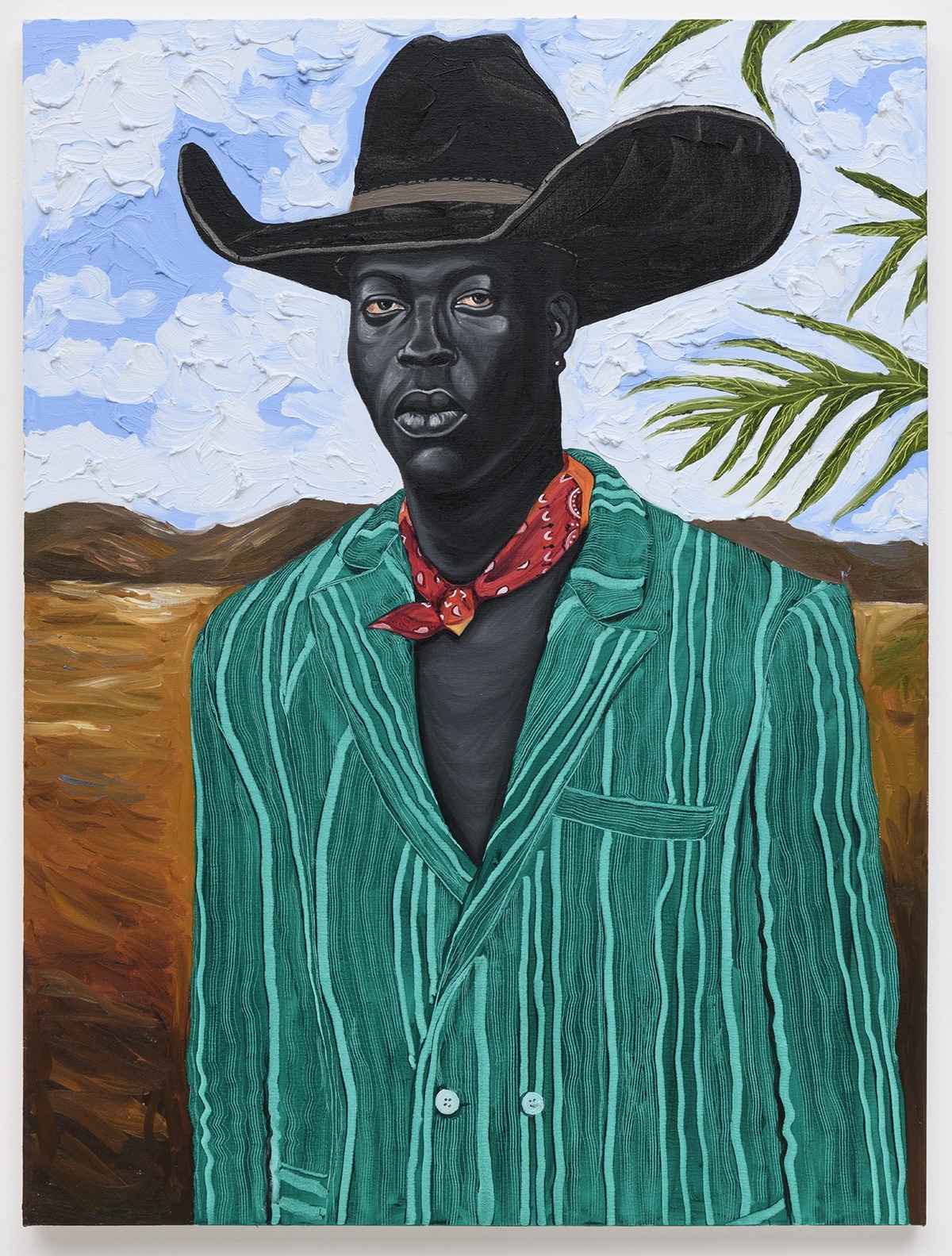

“Red Bandana on Green Suit,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

So are any of your paintings based on real cowboys?

I have not come in contact with any real cowboys yet—which I plan to do. I plan to go see the Compton Cowboys in person. Still, the concept is there, but you need people to execute that. So, like I always do, I try to use somebody to represent the original subject. The reason why I do that is—like when we talked about the representation of Black skin—it could be me, or it could be you. So I always strive to include the ordinary person that is just like you and me, or someone I find to represent that.

And I do that because these are the same kinds of people that I'm trying to talk about. It's just a community. I don't necessarily have to paint a real cowboy to say what I want to say. I'm trying to talk about a certain group of people that look like me and you, that existed but was never talked about. So why not use you or me to talk about these people? A cowboy could be you or me. So, it's kind of like a representation of the real cowboy.

“Rancher,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Alan Shaffer)

What do you hope that people take away from your work?

That they are strong, no matter who they are. Black skin will always be Black skin. It is here to stay, and it won't go anywhere. So they better accept it and just move forward. Also, we are strong people if we put our minds to it. Just keep moving forward, and be open and accepting. That's all.

“Pall Mall,” 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California (Photo: Mario Gallucci)