As the Middle Ages came to an end in the 1400s, a new era of art and culture was born in Italy. The Renaissance—a term derived from the Italian word Rinascimento, or “rebirth”—is often regarded as a golden age of art, music, and literature, which had a profound impact on the course of art history.

Not only did this period introduce essential creative concepts like linear perspective, foreshortening, and anatomical realism, but it also produced famous artists like Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo. For the first time since antiquity, painters sought to make naturalistic depictions of their subjects based on humanist ideals.

Want to see how Italian art developed between the 14th and 16th centuries? Here, we will take a look at 20 of the most famous Renaissance paintings that left their mark on history.

Take a tour of the Italian Renaissance and learn about 20 famous paintings from the era.

Early Renaissance

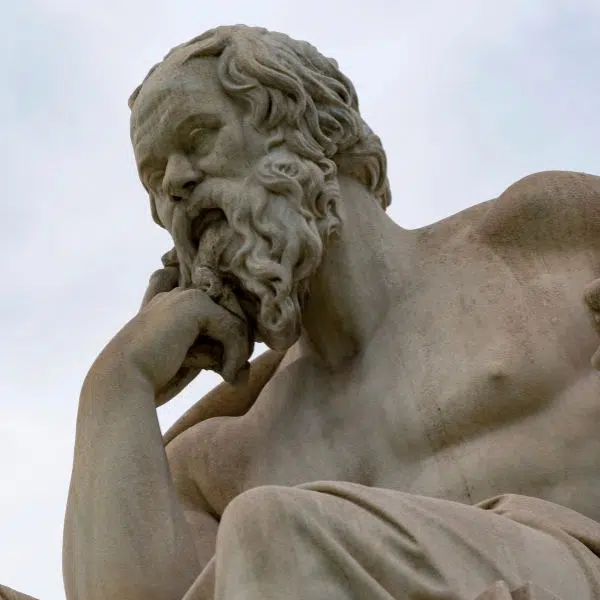

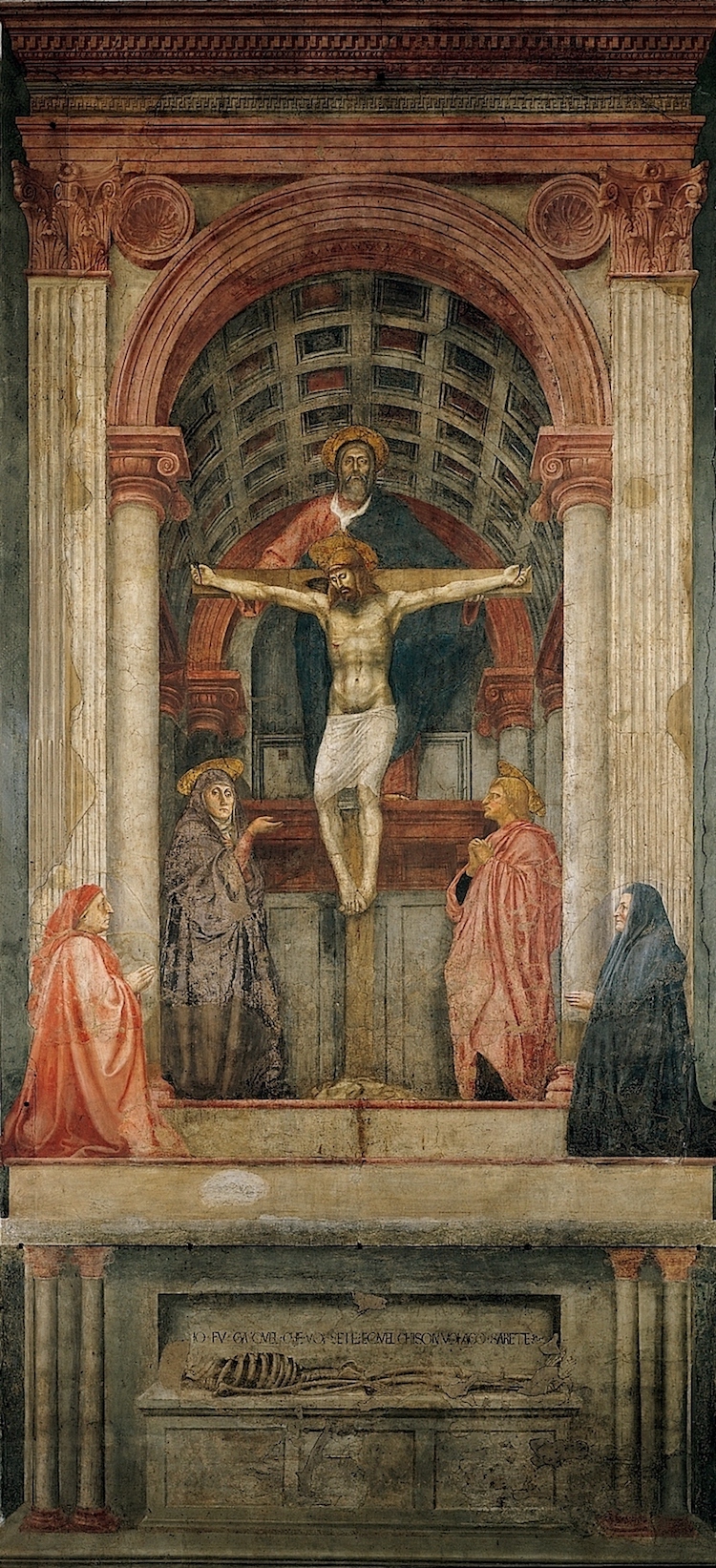

Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427

Masaccio, “Holy Trinity,” c. 1426–28 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Painted in the Dominican Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, the Holy Trinity fresco is the earliest surviving painting to use systematic linear perspective. According to records, Masaccio placed a nail at the vanishing point and attached strings to determine how the lines converged.

Location: Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy

Paolo Uccello, The Battle of San Romano, c. 1435–1460

Paolo Uccello, “Battle of San Romano,” c. 1435–1460 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Artist and mathematician Paolo Uccello created three paintings to represent the battle of San Romano—an event that occurred just outside of Florence in 1432. Although he used perspective to create a sense of depth in the composition, he also rendered the scene in such a way that it resembles a theatrical stage.

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

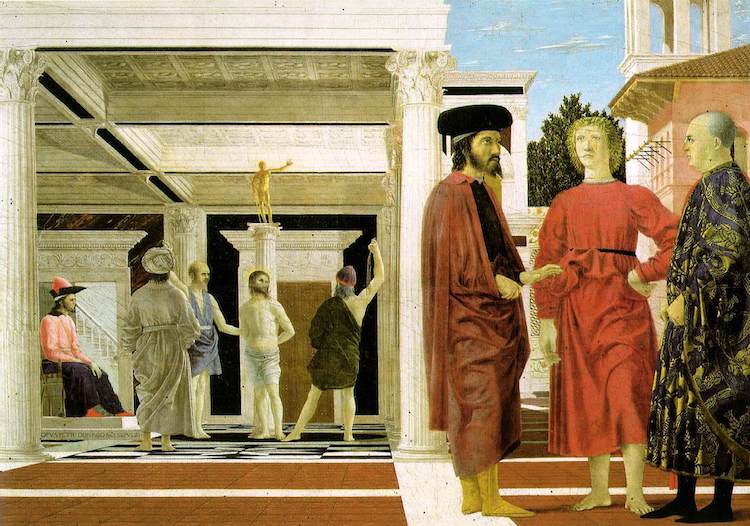

Piero della Francesca, Flagellation of Christ, c. 1468–1470

Piero della Francesca, “The Flagellation of Christ,” c. 1468–70 (Photo: Galleria Nazionale delle Marche via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Piero della Francesca's The Flagellation of Christ is another early example of linear perspective in Renaissance art. Called “the greatest small painting in the world” by art historian Kenneth Clark, it features an unusual composition based on the theme of the flagellation of Christ by the Romans. In the foreground is a trio of men, which possibly represent the past, present, and future, and in the background is Christ being flagellated by a Roman soldier as Pontius Pilate watches on.

Location: Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino, Italy

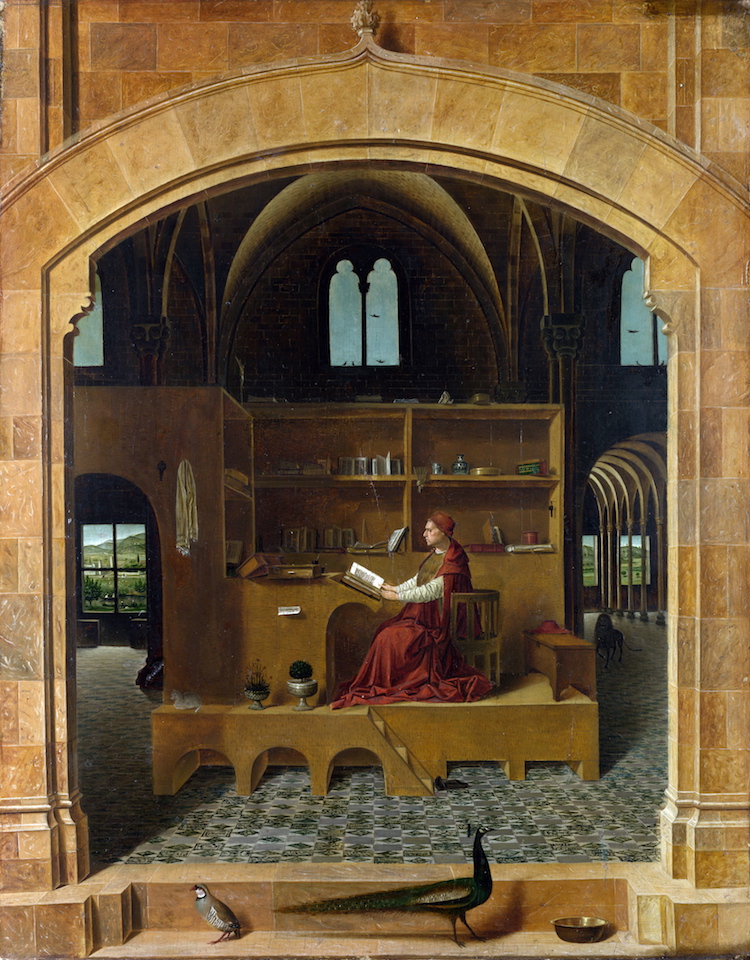

Antonello da Messina, St. Jerome in His Study, c. 1474

Antonello da Messina, “St. Jerome in His Study,” c. 1474 (Photo: National Gallery via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

According to art historian Giorgio Vasari, Antonello da Messina introduced oil painting—the medium popularized in the Northern Renaissance—to Italy. His work St. Jerome in His Study clearly showed the influence of Jan Van Eyck‘s precise style of painting.

The complex design of the piece is based on the different kinds of knowledge: human, natural, and divine. Da Messina uses perspective and geometry to organize the iconography within the architectural space.

Location: National Gallery, London, England

Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation of Christ, c. 1480s

Andrea Mantegna, “Lamentation of Christ,” c. 1480s (Photo: Pinacoteca di Brera via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna was known for experimenting with perspective in his art, and this interest is best exemplified in his tempera painting Lamentation of Christ. This piece depicts the Virgin Mary, Saint John, and Mary Magdalene crying over the dead body of Christ. However, unlike other Lamentations, Mantegna employs dramatic foreshortening in the painting so that the viewer is staring at Christ's body feet-first.

Location: Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy

Pietro Perugino, Delivery of the Keys, c. 1481–1482

Pietro Perugino, “Delivery of the Keys,” c. 1481–2 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Although his pupil Raphael surpassed him in fame, Pietro Perugino made significant contributions to Renaissance art. Delivery of the Keys is one of his most important frescoes, which is situated in the Sistine Chapel.

It portrays the scene in Matthew 16 in which Jesus gives Saint Peter the keys to the kingdom of heaven. The piece is an excellent example of how the artist used linear perspective to give depth to his background.

Location: Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, Italy

Sandro Botticelli, Primavera, c. 1477–82

Sandro Botticelli, “Primavera,” c. 1477–82 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Sandro Botticelli painted Primavera—the first of his mythological works—around 1480 for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici's private estate. It is considered a groundbreaking Renaissance painting because it reflects the shift away from Catholic iconography in art and scenes from Greek and Roman mythologies. Case in point, this painting depicts an allegorical celebration of Spring, with the Roman goddess Venus placed in the center.

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks, 1483–1486

Leonardo da Vinci, “Virgin of the Rocks,” c. 1483–6 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Although there are two versions of Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks, the earlier one—which is housed at the Louvre—is considered to be painted entirely by him. It uses a triangular composition to portray the Virgin Mary, the baby Jesus, an infant John the Baptist, and an angel in an obscure, verdant background. Like other da Vinci paintings, it utilizes considerable sfumato technique.

Location: Louvre Museum, Paris, France

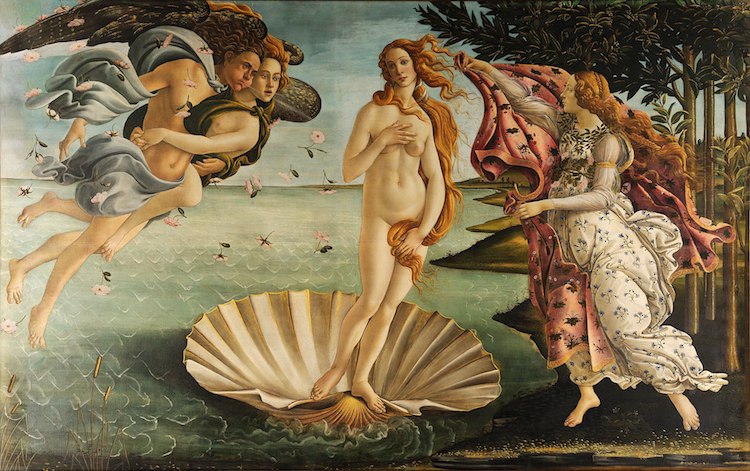

Sandro Botticelli, Birth of Venus, c. 1484–1486

Sandro Botticelli, “The Birth of Venus,” c. 1484–6 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Created in the late 15th century, The Birth of Venus is Botticelli's other famous mythological painting. It shows a recently born Venus, the Roman goddess associated with love and beauty, standing nude in an enlarged scallop shell. She is flanked by three other figures from Classical mythology associated with nature. Although this work is synonymous with Renaissance art today, the prominence of the female nude was unprecedented at the time.

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

High Renaissance

Leonardo da Vinci, Lady With an Ermine, c. 1489–1491

Leonardo da Vinci, “Lady with an Ermine,” c. 1489–91 (Photo: Czartoryski Museum via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Years before Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci produced the Mona Lisa, he made another important portrait. Entitled Lady with an Ermine, this oil painting is an example of High Renaissance portraiture and the chiaroscuro style.

It depicts a young woman with plated hair holding a large, white weasel (also called an ermine) in her arms. While this painting is an excellent display of da Vinci's interest in anatomical realism, it also uses the ermine as a symbol with meanings related to the subject of the portrait and its patron.

Location: Czartoryski Museum, Krakow, Poland

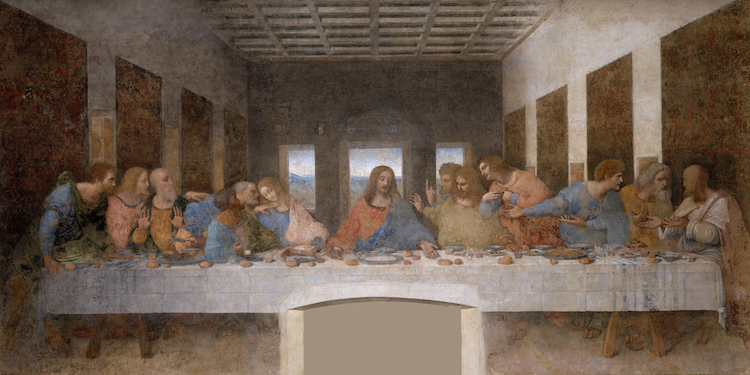

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495–8

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Last Supper,” 1495–8 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Since its completion at the end of the 15th century, The Last Supper has captivated audiences with its impressively large scale, unique composition, and mysterious subject matter. Da Vinci's patron, Ludovico Sforza, asked him to paint Jesus' final meal as described in the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Bible.

Interestingly, Leonardo opted to illustrate the moment Jesus tells his followers that one of them will betray him, placing much of the painting's focus on the figures' individual expressive reactions.

Location: Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy

Raphael, The Marriage of the Virgin, 1504

Raphael, “The Marriage of the Virgin,” 1504 (Photo: Pinacoteca di Brera via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Renaissance master and child prodigy Raphael created The Marriage of the Virgin when he was just 21 years old. Inspired by the paintings of his master Pietro Perugino, this work portrays the marriage ceremony of Mary and Joseph.

The art historian Giorgio Vasari commented on the improvements, saying, “There is a temple draw in perspective with such evident care that it is marvelous to behold the difficulty of the problems which he has there set himself to solve.”

Location: Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy

Michelangelo, Doni Tondo, 1506

Michelangelo, “Doni Tondo,” 1506 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Before Michelangelo commenced his illustrious Sistine Chapel ceiling, he made his only finished panel painting. The Doni Tondo celebrates the marriage of Agnolo Doni with a portrait of the Holy Family, including the baby Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. The vibrant color palette and sculptural modeling of the figures are typical of Michelangelo's painting style.

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, 1506

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Mona Lisa,” c. 1503–6 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Renowned for both its curious iconography and its unique history, da Vinci's Mona Lisa has become one of the most famous paintings in art history. The Renaissance portrait features a female figure—believed by most to be Lisa Gherardini, the wife of cloth and silk merchant Francesco Giocondo—from the waist up. She is shown seated in a loggia, or a room with at least one open side.

Behind her is a hazy and seemingly isolated landscape imagined by the artist and painted using sfumato, a technique resulting in forms “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke or beyond the focus plane.”

Location: Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Giorgione, The Tempest, c. 1506–8

Giorgione, “The Tempest,” c. 1506–8 (Photo: Gallerie dell'Accademia via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Towards the end of the High Renaissance, the Venetian school of painting began to flourish, emphasizing color over line. Giorgione was one of the pioneering painters of this style, and The Tempest remains one of his most beloved and most ambiguous works of art.

In the foreground, it features an anonymous woman breastfeeding her baby on the righthand-side, and a soldier carrying a long staff standing on the left. The title derives from the impending storm occurring in the background, which is emphasized in the darkened color palette used in the foreground.

Location: Accademia Gallery, Florence, Italy

Raphael, The School of Athens, 1509–1511

Raphael, “The School of Athens,” 1509–11 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The School of Athens is one of the four wall frescoes Raphael painted in the Stanza della Segnatura, in the Papal Palace. It is considered a masterpiece for how it merges art, philosophy, and science into one painting. Among the many figures depicted in the piece are Greek philosophers Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates, and mathematicians Euclid and Pythagoras.

Location: Apostolic Palace, Vatican Museums, Vatican City, Italy

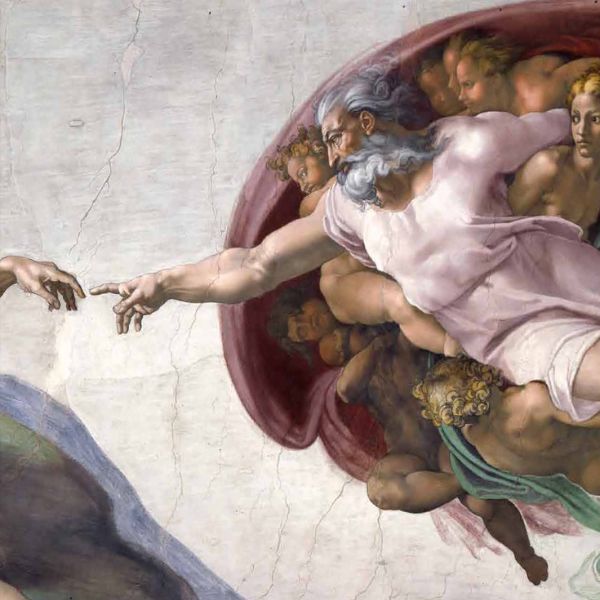

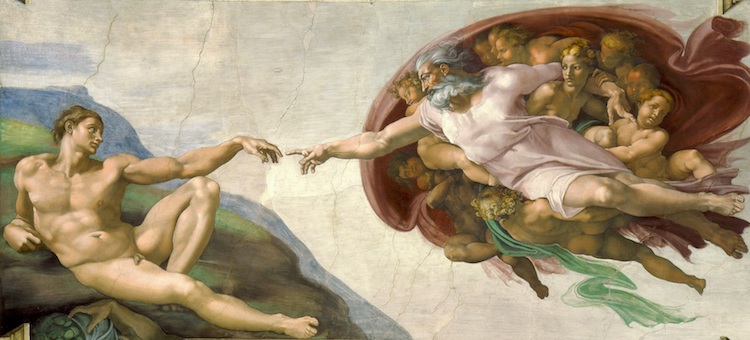

Michelangelo, Creation of Adam, c. 1508–1512

Michelangelo, “Creation of Adam,” c. 1508–12 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Michelangelo spent four years painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel for Pope Julius II. It is not only renowned for its incredible scale, but also for its complex composition and Classical inspirations.

Among the many panels that make up the design of the ceiling, the Creation of Adam remains the most famous. It portrays Adam in a languid pose with one arm extended, just before he is to receive life from God's touch.

Location: Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, Italy

Titian, Sacred and Profane Love, 1514

Titian, “Sacred and Profane Love,” 1514 (Photo: Galleria Borghese via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Among the great names of the Italian Renaissance—Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael—there is also Titian, the master of color. Sacred and Profane Love is one of the artist's early paintings, which was made to commemorate the marriage of the man who commissioned it. While there are many different theories that explore the identities of the central figures, the painting's true intentions remain a mystery. In spite of this, the work is an excellent example of Titian's mastery of color and composition.

Location: Borghese Gallery, Rome, Italy

Late Renaissance

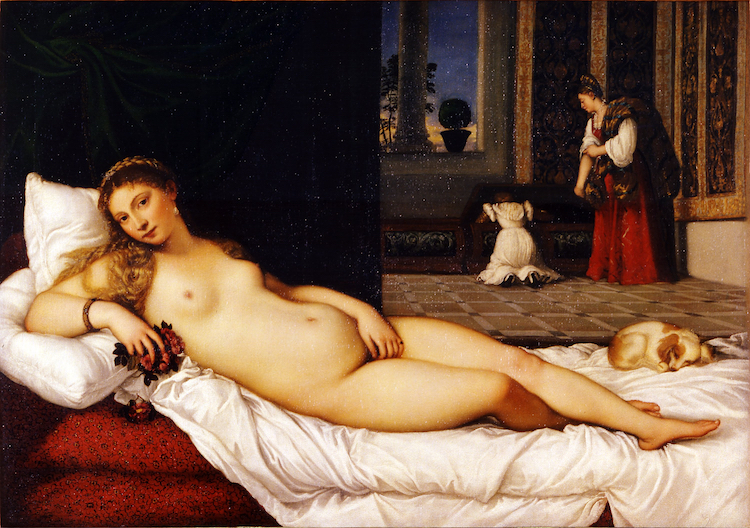

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538

Titian, “Venus of Urbino,” 1538 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

After the death of Giorgione in 1510, and Giovanni Bellini in 1516, Titian was the leading upholder of the Venetian style. Venus of Urbino depicts a naked woman reclining on a bed inside of an ornate room. Similar to Sacred and Profane Love, the unknown identity of the woman in Venus of Urbino and the meaning of the iconography has led to many different interpretations of the work. It has inspired many similar paintings, including Manet's Olympia.

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

Michelangelo, The Last Judgement, 1541

Michelangelo, “The Last Judgment,” 1536–41 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Several decades after Michelangelo completed the Sistine Chapel ceiling, he returned to the same building to add another fresco, this time covering the entire altar wall. The Last Judgment captures the Second Coming of Jesus Christ and God's final judgment of humanity.

While this subject was not uncommon during the Renaissance, Michelangelo's interpretation stands apart for its 300 mostly nude figures and its conflation with some mythological elements—both of which made the fresco controversial among Michelangelo's contemporaries. The work is also a look into future artistic movements, with elongated figures foreshadowing the Mannerism that followed the Renaissance and the dynamic movements looking forward to the Baroque.

Location: Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, Italy

Related Articles:

20 Famous Paintings From Western Art History Any Art Lover Should Know

Who Was Albrecht Dürer? Learn About the Pioneering Northern Renaissance Printmaker

20 Famous Artists Everyone Should Know, From Leonardo da Vinci to Frida Kahlo

10 Artists Who Were Masters of Drawing, From Leonardo da Vinci to Pablo Picasso