Since the emergence of the Italian Renaissance, the history of Western art has taken a fascinating course through different stylistic genres. While 15th-century painting focused on portraying the ideal, the subsequent movements explored many other aesthetics and ideas, often in reaction to their historical predecessor. And although there are many remarkable paintings to study from these different art movements, we’ve narrowed down the expansive list to 31 iconic works that span from the end of the 15th century all the way to the first half of the 1900s.

Among this list of masterpieces are some that are so well known they’ve become a part of popular culture, as well as others that, while famous in art circles, may not be as familiar. For instance, René Magritte’s Surrealist painting Treachery of Images, which features a rendering of a brown pipe accompanied by the recognizable phrase “This is not a pipe,” has been referenced in film as well as video games. Similarly, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa continues to inspire authors and filmmakers from around the world. On the other hand, some paintings that have eluded the same attention include Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Impressionist gem, Bal du Moulin de la Galette, and Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase.

Want to brush up on your art history knowledge? Scroll down to take a short-listed tour of 31 of Western art history’s most famous paintings. Many of them are by famous artists themselves.

Brush up on your art history knowledge by learning about these famous paintings.

Northern Renaissance

Jan Van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

Jan Van Eyck, “The Arnolfini Portrait,” 1434 (Photo: National Gallery via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Born in what is now Belgium, artist Jan van Eyck was an early master of the oil medium and used it to create meticulously detailed compositions. His most prominent work, The Arnolfini Portrait, remains an icon of the Northern Renaissance—encapsulating many of the aesthetic ideals and technical innovations of the time period. It depicts a wealthy merchant—presumed to be Giovanni di Nicolau di Arnolfini—and his wife in a lavishly decorated room which showcases their opulent wealth.

Fun fact: On the back wall of the room is a convex mirror that shows a reflection of two people, one of whom is very likely Van Eyck. The mirror itself is thought to suggest the eye of God observing the scene.

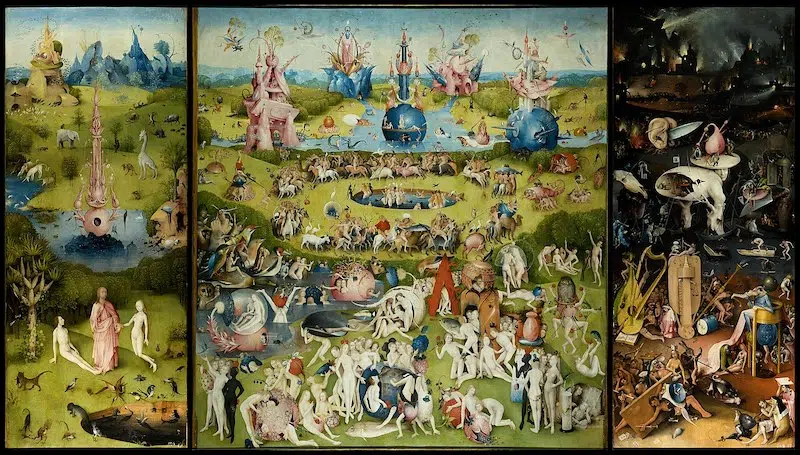

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1490

Hieronymus Bosch, “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” circa 1490 (Photo: Hieronymus Bosch via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Little is known about artist Hieronymus Bosch. The enigmatic artist didn’t date his work, so it’s unknown when exactly he created The Garden of Earthly Delights. It’s estimated that this monumental masterpiece was painted between 1490 and 1510.

Regardless of timing, The Garden of Earthly Delights is Bosch’s most complex creation. The triptych depicts three distinct scenes: the left panel shows the Garden of Eden; the middle panel depicts a surreal (and chaotic) earthly paradise; and the right panel is a nightmarish vision of Hell. Each oil painting depicts fantastical creatures, hybrid animals, and strange machines.

Fun fact: The common title for the work is the result of modern viewers. The Garden of Earthly Delights is what the name for the middle panel is, which has been adopted for the entire piece.

Italian Renaissance

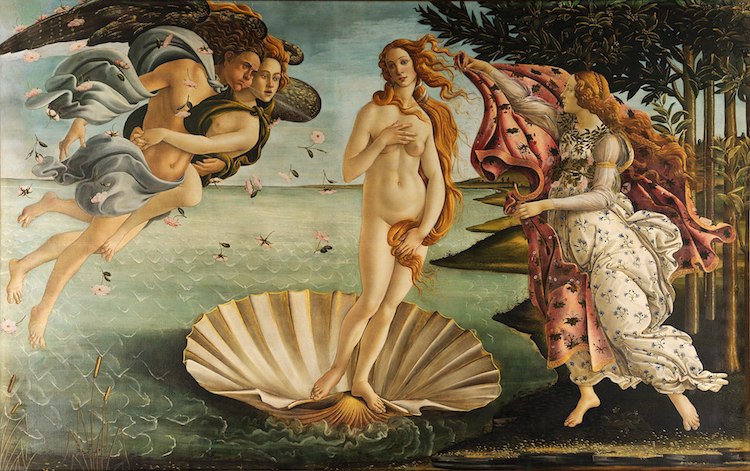

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1484–6

Sandro Botticelli, “The Birth of Venus,” c. 1484–1486 (Photo: Uffizi via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Created by Sandro Botticelli in the Early Renaissance (or the Quattrocento), The Birth of Venus is a stylistic depiction of the mythological Roman goddess, Venus. It is one of the first Renaissance paintings to display Classical inspiration and a prominent nude female figure.

Fun fact: The nudity depicted in The Birth of Venus was unusual—and rather daring—at the time.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, c. 1495–1498

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Last Supper,” 1495–8 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Since its completion at the end of the 15th century, The Last Supper has captivated audiences with its impressively large scale, unique composition, and mysterious subject matter. Leonardo da Vinci’s patron, Ludovico Sforza, asked him to paint Jesus’ final meal as described in the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Bible.

Fun fact: Interestingly, Leonardo opted to illustrate the moment Jesus tells his followers that one of them will betray him, placing much of the painting’s focus on the figures’ individual expressive reactions.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, c. 1503–1506

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Mona Lisa,” c. 1503–1506 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Almost everyone is familiar with the Mona Lisa’s enchanting smile. Painted in the High Renaissance by polymath Leonardo da Vinci, it exhibits naturalistic painting techniques as well as a smokey background using sfumato.

Fun fact: The Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in 1911, but it seems the thief made the painting famous. Newspapers spread the story of the crime worldwide, sparking international interest in the painting. When the artwork finally returned to the Paris museum two years later, it became celebrated as a masterpiece.

Raphael, The School of Athens, 1509–1511

Raphael, “The School of Athens,” 1509–11 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The School of Athens is one of the four wall frescoes Raphael painted in the Stanza della Segnatura, in the Papal Palace. It is considered a masterpiece for how it merges art, philosophy, and science into one painting. Among the many figures depicted in the piece are Greek philosophers Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates, and mathematicians Euclid and Pythagoras.

Fun fact: Plato’s gesture toward the sky is thought to indicate his Theory of Forms. This philosophy argues that the “real” world is not the physical one, but instead a spiritual realm of ideas filled with abstract concepts and ideas. Conversely, Aristotle’s outstretched hand is a visual representation of his belief that knowledge comes from experience. Empiricism, as it is known, theorizes that humans must have concrete evidence to support their ideas and is very much grounded in the physical world.

Michelangelo, The Sistine Chapel ceiling, 1508–1512

Photo: Stock Photos from Creative Lab/Shutterstock

Renaissance artist Michelangelo spent four years painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel for Pope Julius II. It is not only renowned for its incredible scale, but also for its complex composition and Classical inspirations. The most famous part of the ceiling is The Creation of Adam fresco.

Fun fact: Michelangelo was reluctant to take up the job. When he was asked by Pope Julius II to paint the ceiling, he made it very clear that he hated painting and preferred sculpture. He even wrote a poem expressing his frustrations.

Baroque

Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1599–1600

Caravaggio, “The Calling of St. Matthew,” 1599–1600 (Photo: Wikipedia, Public domain)

Michelangelo Merisi—better known as Caravaggio—was a masterful Italian Baroque painter who pushed boundaries, both in his artistic and personal life. His work, The Calling of St. Matthew, depicts an informal, natural gathering of figures with a dramatic use of light and shadow—the trademark of his style. Dressed in contemporary clothing, the characters appear lifted from a genre scene rather than a traditional religious painting.

Fun fact: The identity of Matthew in the painting is still debated. While most believe it is the bearded man pointing to himself, others believe that the bearded man is actually directing the viewer’s attention to the man slumped over the table.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656–7

Diego Velázquez, “Las Meninas,” 1656–1657 (Photo: Museo del Prado via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Spanish artist Diego Velázquez was the court painter for King Philip IV and known for his expressive portraits which captured the physical likeness and personality of his subjects. Las Meninas is his most revered work that is still lauded by art historians today for its complex design. It shows the infanta Margaret Theresa surrounded by ladies in waiting, a chaperone, a bodyguard, a chamberlain, and even Velázquez himself.

Fun fact: The King and Queen are included in the painting. Above the princess’s head, there’s a dark wooden frame. Within it is her father and mother, King Philip IV of Spain and Mariana of Austria.

Dutch Golden Age

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Night Watch, 1642

Rembrandt, “The Nightwatch,” 1642 (Photo: Rijksmuseum via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

In the 17th century, Dutch artists became inspired by Northern Renaissance painting techniques in an era known as the Dutch Golden Age. Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Night Watch is a massive group portrait in which the figures are nearly life-size. It showcases the artist’s dramatic use of light and shadow.

Fun fact: The painting is viewed by around 4,000 to 5,000 visitors daily at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

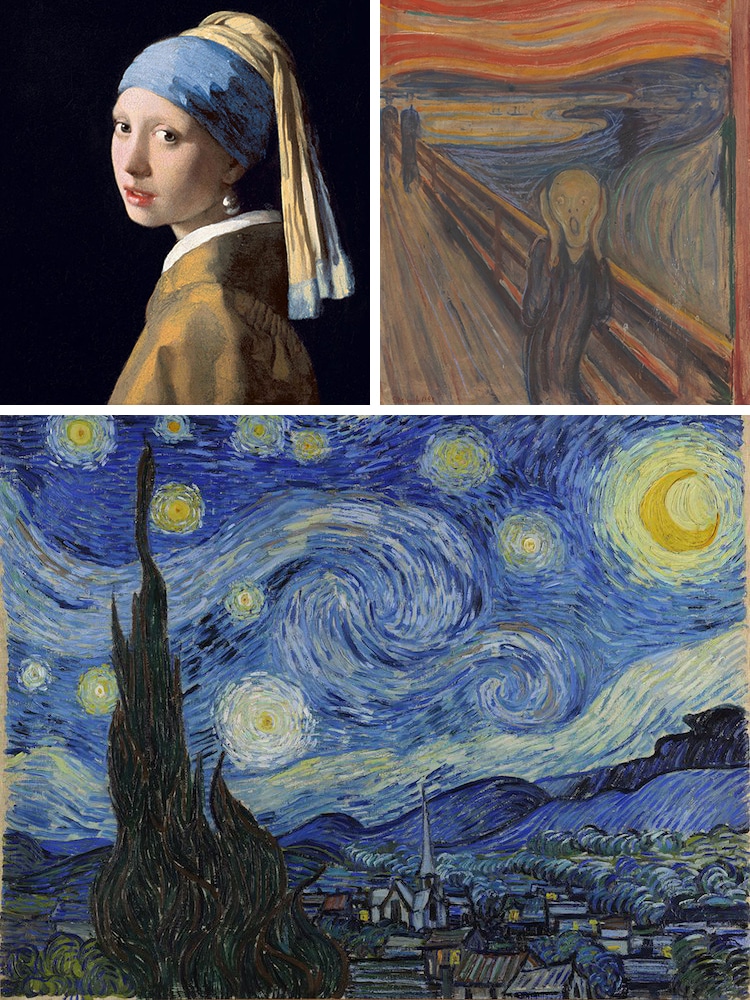

Johannes Vermeer, Girl With a Pearl Earring, c. 1665

Johannes Vermeer, “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” c. 1665 (Photo: Mauritshuis via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Another of the most acclaimed paintings to emerge from this period is Johannes Vermeer’s enticing portrait, Girl With a Pearl Earring. It portrays an anonymous woman wearing “exotic” blue-and-yellow clothing and sitting before a stark black background.

Fun Fact: Girl with a Pearl Earring is sometimes nicknamed the “Mona Lisa of the North.” This is partially due to the subject’s captivating expression, and because of the mystery surrounding the piece itself.

Rococo

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, c. 1767

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, “The Swing,” c. 1767 (Photo: The Wallace Collection via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Following the extravagance and power of Baroque art came the lighthearted and flirtatious Rococo movement, which blossomed in 18th-century France before spreading to other European countries. The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard exemplifies the aesthetic of this decorative style, featuring a whimsical narrative, pastel colors, and fluid forms.

Fun fact: The Swing was commissioned by the Baron de Saint-Julien, who wanted a flirtatious portrait of his mistress. The Baron was very clear in his salacious intentions, specifically asking that in the painting his mistress was pushed on a swing by a bishop, while he (the Baron) looked up his mistress’s dress. Fragonard did make one omission from the original request and exchanged the figure of a bishop with the more acceptable character of a cuckolded husband.

Neoclassical

Jacque-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1801–1805

Jacques-Louis David, “Napoleon Crossing the Alps,” Version 2, 1801–1805 (Photo: Belvedere via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

As the preeminent artist of the Neoclassical style, Jacques-Louis David produced art that was unlike the Rococo status quo—with few colors, minimalist but balanced compositions, and depictions of classical subject matter. When Napoleon rose to power, David aligned himself with the ruler of France and made art in support of the new regime. His equestrian portrait Napoleon Crossing the Alps has become the best-known image of Napoleon, portraying the emperor as he leads his army through the Great St. Bernard Pass.

Fun fact: David made five versions of this portrait between 1801–1805, with minor differences between them. The first version featured Napoleon wearing an ochre-colored cape, whereas all of the subsequent versions depict him wrapped in a red cape.

Romanticism

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of The Medusa, 1818–1819

Théodore Géricault, “The Raft of The Medusa,” 1818–9 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The Romantic art movement emphasized emotion, the sublimity of nature, and the individual. Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of The Medusa depicts a historical shipwreck off the coast of modern-day Mauritania, where sailors survived treacherous conditions to find a safe haven. The painting’s use of scale and drama makes it a cornerstone of French Romanticism.

Fun fact: The Raft of The Medusa painting is huge, measuring around 16 feet by 23.5 feet. The raft itself was even bigger, measuring 23 feet by 66 feet.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People, 1830

Eugène Delacroix, “Liberty Leading the People,” 1830 (Photo: Louvre via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Liberty Leading the People is a dramatic large-scale painting by French artist Eugène Delacroix. Created during the tumultuous French Revolution, it captures the spirit of the people’s uprising.

Fun fact: The woman in the composition is known as “Marianne.” She has been the personification of the French Republic ever since the first French Revolution of 1789.

Realism

James McNeill Whistler, Whistler’s Mother, 1871

James McNeill Whistler, “Whistler’s Mother,” 1871 (Photo: Musée d’Orsay via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Whistler’s Mother (also known as Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1) is a portrait of the artist James McNeill Whistler’s mother, 67-year-old Anna McNeill Whistler. In addition to showcasing Whistler’s focus on color, which he explored through shape, form, and composition, the austere painting also illustrates the artist’s perception of his pious mother, whose presence in London—previously the setting of his Bohemian lifestyle—he described as a “general upheaval” in a letter to fellow artist and friend Henri Fantin-Latour.

Fun fact: As a firm believer in “art for art’s sake,” Whistler entitled the portrait Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 because he did not believe the identity of the subject was important to audiences. Even so, the picture is best known by its colloquial name, Whistler’s Mother.

Realism—Impressionism

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, 1863

Édouard Manet, “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” 1863 (Photo: Musée d’Orsay via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Manet’s large-scale masterpiece, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (or The Luncheon on the Grass), bridges the gap between the Realist and Impressionist art movements with its modern approach to style and subject matter. Featuring a nude woman picnicking in the company of two well-dressed men, it derives inspiration from Classical paintings of female nudes while placing it in a contemporary setting.

Fun fact: The clothed men in the painting were Manet’s relatives—his brother, Eugène Manet, and his future brother-in-law, Dutch sculptor Ferdinand Leenhoff. The nude woman is Victorine-Louise Meurent, a popular muse of Parisian painters during the late 1800s. She was nicknamed “La Crevette” (The Shrimp) because of her red hair and rosy complexion.

Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882

Édouard Manet, “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère,” 1882 (Photo: The Courtauld Institute of Art via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Completed in 1882, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère was Manet’s last major work and the culmination of his unique—and to some, controversial—approach to painting. Set in a crowded bar, the work portrays a somber barmaid attending to a gentleman in a top hat. Manet renders the main figures, objects, and interior with expressive brushstrokes and close attention to the details.

Fun fact: This painting is based on a real-life nightclub in Paris called the Folies-Bergère. In the late 19th century, this establishment was incredibly popular among artists as well as middle and upper-class Parisians for its array of entertainment including cabaret, ballet, and acrobatics, to name a few.

Impressionism

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1872

Claude Monet, “Impression, Sunrise,” 1872 (Photo: Musée Marmottan Monet via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Impression, Sunrise depicts a hazy blue-hued seascape dotted with small boats and a bright orange sun. In fact, its radical use of expressive brushstrokes to portray a sunrise is what sparked the Impressionist art movement and named its creator, Claude Monet, the “Father of Impressionism.”

Fun fact: The painting depicts the harbor of LeHavre in France, but Monet felt there wasn’t enough detail to title the painting after the location. Therefore, the name Impression, Sunrise was given. Monet titled most of his paintings with “Impression” for this reason.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette, 1876

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “Bal du moulin de la Galette,” 1876 (Photo: Musée d’Orsay via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The Bal du moulin de la Galette, or the Dance at the Moulin de la Galette, is among Renoir’s most celebrated pieces. Like many other Impressionist works, it was painted en plein air, and offers a glimpse into life and leisure during France’s Belle Époque.

Fun fact: The subjects in Bal du moulin de la Galette were fellow artists, scholars, and close friends to Renoir. The painter asked them to join him at Maison Fournaise to pose for the composition.

Post-Impressionism

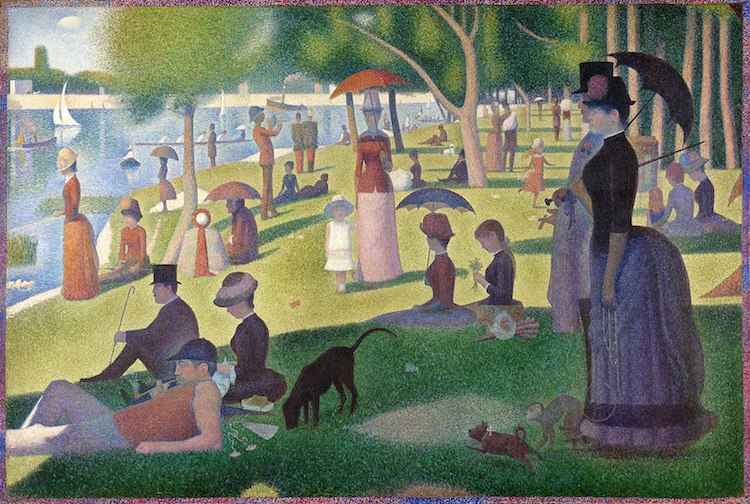

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–6

Georges Seurat, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,” 1884–6 (Photo: Art Institute of Chicago via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

French artist and color theorist Georges Seurat was one of the inventors of Pointillism, a painting technique that applies paint to the canvas using small dots of color. His massive magnum opus, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte displays his mastery of the unique style.

Fun fact: Seurat was just 26 years old when he completed this painting.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889

Vincent van Gogh, “The Starry Night,” 1889 (Photo: MoMA via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

While the Impressionist movement was preoccupied with portraying light in its painting, the Post-Impressionist movement focused on color. And few artists are as renowned for their use of color as Vincent van Gogh. The Starry Night was created late into the Dutch painter’s short career and depicts the view from his window in the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

Fun fact: This was not Van Gogh’s first Starry Night. The year before, in 1888, the artist painted his original Starry Night, sometimes known as Starry Night Over the Rhône.

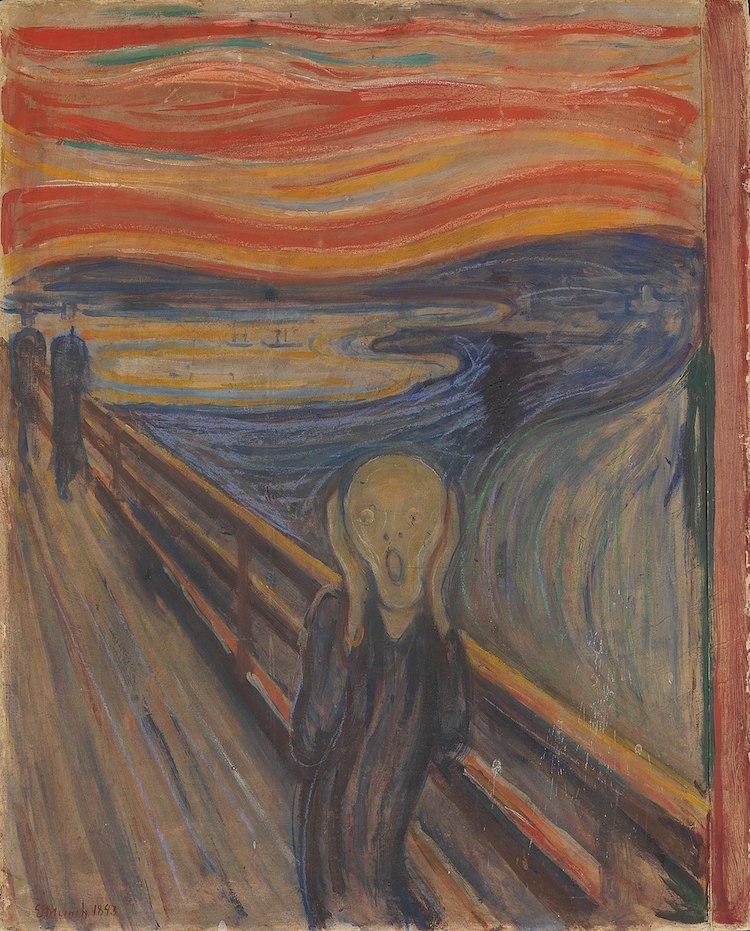

Expressionism

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893

Edvard Munch, “The Scream,” 1893 (Photo: National Gallery of Norway via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

One of the pioneers of Norwegian Expressionism, Edvard Munch’s stylistic approach to conveying emotion, particularly feelings of anguish, is best displayed in his iconic masterpiece, The Scream.

Fun fact: This painting inspired the killer’s mask in Wes Craven’s movie franchise, Scream. The director said of the painting: “It’s a classic reference to just the pure horror of parts of the 20th century, or perhaps just human existence.”

Vienna Secession

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907–8

Gustav Klimt, “The Kiss,” oil and gold leaf on canvas, 1907–1908 (Photo: Belvedere via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt was famous for his dazzling use of gold and his masterpiece The Kiss is no different. Made in the Vienna Secession art movement—which is closely related to Art Nouveau—this intimate portrait captures a tender moment between a pair of lovers. He uses a flat, two-dimensional composition to enhance the luster of the gold leaf.

Fun fact: Love—whether romantic, platonic, or familial—is a common theme in Klimt’s work. “Whoever wants to know something about me,” he said, “should look attentively at my pictures and there seek to recognize what I am and what I want.”

Cubism

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907

Pablo Picasso, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” 1907 (Photo: MoMA via Wikimedia Commons, Fair use)

Few artists can boast a portfolio as numerous and diverse as Pablo Picasso. A pioneer of several different styles, he is perhaps best known for his works in Cubism. And while Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is often considered to be a proto-Cubist painting, it still exhibits an interest in shapes, perspective, and simplification of forms.

Fun fact: Henri Matisse was Picasso’s rival for years, and when Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was revealed, Matisse publicly criticized the painting. He believed it undermined modern art.

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912

Marcel Duchamp, “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,” 1912 (Photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons, Fair use)

Although Marcel Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was initially rejected by the Cubists as being too Futurist in style, the work was subsequently recognized as an example of both movements and a modern masterpiece. Like the Cubists, it utilizes fragmentation and simplification of shapes, and like the Futurists it portrays movement.

Fun fact: Duchamp’s brothers hated the piece and tried to censor it. Duchamp had hoped to debut the painting in the Salon des Indépendants’ spring exhibition of Cubist works. However, it was rejected by the committee, and the artist’s brothers urged him to withdraw the work or paint over the piece. Duchamp refused to change his artwork and later recalled, “I said nothing to my brothers. But I went immediately to the show and took my painting home in a taxi. It was really a turning point in my life, I can assure you. I saw that I would not be very much interested in groups after that.”

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937

Painted towards the end of the Cubist art movement, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica is one of the most prominent examples of anti-war art. It captures the anguish of both people and animals that is caused by unnecessary violence.

Fun fact: The main subjects in the painting are women. One powerful figure is depicted screaming in agony as she holds a dead baby in her arms. Another holds her arms in the air holding an oil lamp, signifying hope.

Surrealism

René Magritte, The Treachery of Images, 1929

René Magritte’s Surrealist paintings are known for their unique sense of irony and wit. One of his most famous pieces, The Treachery of Images, insists that the pipe depicted “is not a pipe” because it is simply a representation of one.

Fun fact: The painting received some bad reviews from critics who thought it suggested the idea of nihilism. In an interview, Magritte defended himself by stating, “The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it’s just a representation, is it not? So if I had my picture ‘This is a pipe,’ I’d have been lying!”

Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931

The Persistence of Memory was painted at the height of the Surrealist art movement and is considered to be Salvador Dalí’s most iconic work. It displays outlandish subject matter evocative of a dreamscape. Even today, the melting clock is synonymous with the Spanish artist’s name.

Fun fact: Dalí was probably hallucinating when he painted the piece. Around the time of the artwork’s creation, the surrealist was practicing his “paranoiac-critical method.” Dalí would attempt to enter a state of self-induced psychotic hallucinations so that he could create what he called “hand-painted dream photographs.”

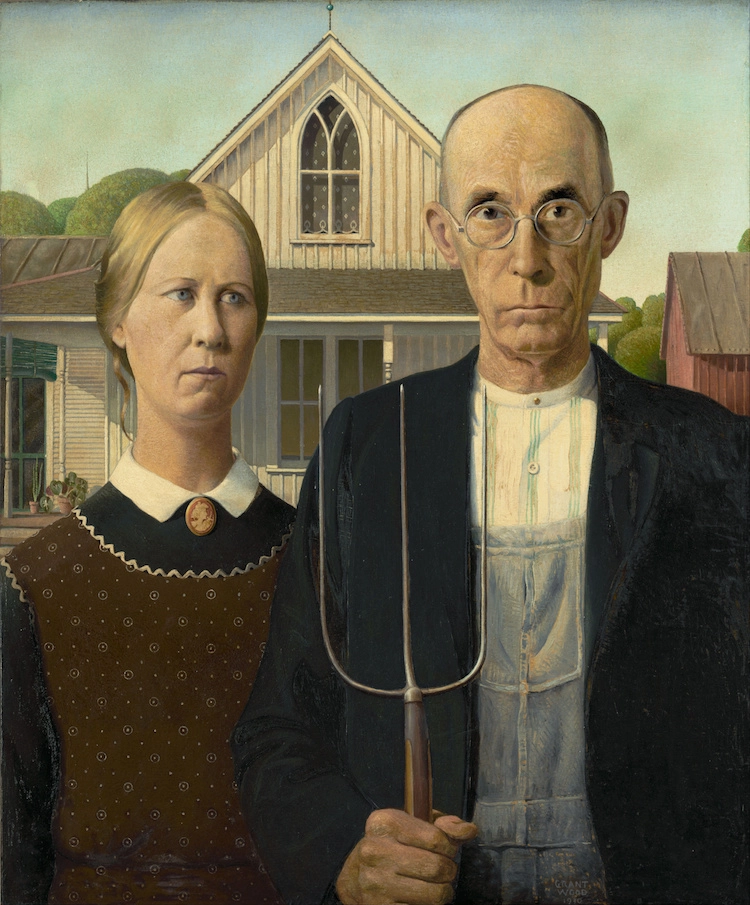

20th-Century American Art

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930

Grant Wood, “American Gothic,” 1930 (Photo: Art Institute of Chicago via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Featuring a stoic portrait of a farmer and his daughter, Grant Wood’s American Gothic offers a fascinating glimpse into life in the rural United States. While many have misconstrued its meaning and misinterpreted its subject matter since its debut in 1930, this depiction of small town life remains one of art history’s biggest icons.

Fun fact: The house in the painting is based on a real-life structure that Wood came across in Iowa. Known as the Dibble House, this humble abode was built in 1881 in a Gothic Revival style called Carpenter Gothic. In addition to its Gothic elements, however, Wood was drawn to its characteristically “rural” appearance, typified by its small stature, cream-colored walls, and shingled roof. When he spotted the home, it immediately caught his eye—and sparked his imagination.

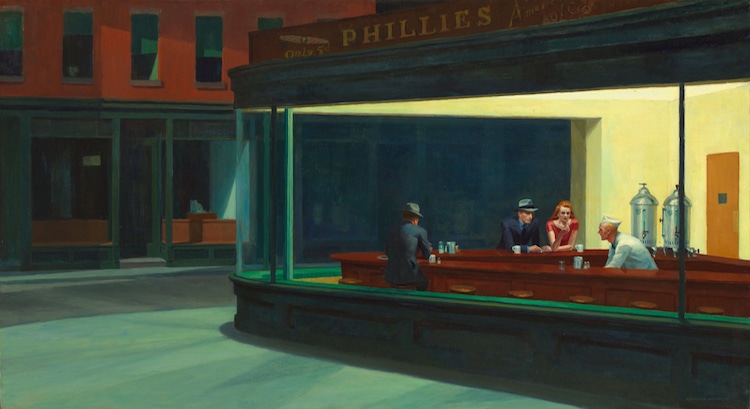

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942

Edward Hopper, “Nighthawks,” 1942 (Photo: Art Institute of Chicago via Wikipedia, Public domain)

Nighthawks offers a glimpse into artist Edward Hopper’s perceptions of modern American life—particularly, in New York City. Unlike his contemporaries who opted to capture the city’s bright lights, buzzing atmosphere, and booming industry, however, Hopper instead focused on the prevalent yet underrepresented loneliness of its residents.

Fun fact: His wife, Josephine or “Jo,” often wrote detailed annotations for Hopper’s preparatory drawings. For Nighthawks, she said, “Night + brilliant interior of cheap restaurant. Bright items: cherry wood counter + tops of surrounding stools; light on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade green tiles 3/4 across canvas—at base of glass of window curving at corner. Light walls, dull yellow ocre [sic] door into kitchen right.”

Want to see these masterpieces in person? Check out our guide on where to find some of the most famous art.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

14 of Art History’s Most Horrifying Masterpieces

12 Essential Art History Books for Beginners

Set Sail on a Journey Through 9 of Art History’s Most Important Seascape Paintings

33 Art History Terms to Help You Skillfully Describe a Work of Art